Features & Columns

LION: Wayne Thompson, son of the couple that started the Lost World, contributed a lion to the exhibit.

LION: Wayne Thompson, son of the couple that started the Lost World, contributed a lion to the exhibit.

Celebrities made

appearances: Lorne Greene, Bing Crosby and the Sweathogs from Welcome Back Kotter stopped by. Local radio stations held promotions—bringing the likes of Barbara Mandrell and Johnny Paycheck to the park. And Kodak provided free loaner cameras for those who forgot theirs at home. Parking was free and Frontier Village would even stay open late if the park was busy at closing time.

"You could sit on a bench and just watch people," says former Frontier Village employee Allen Weitzel, rattling off the options. "You could sit on a bench and eat and drink a beer. You could also turn your kids loose and run around. The kids could ride anything they wanted to. There were different ticket packages so everybody could fit their own budget. And gunfights. You couldn't do those in today's market."

Most of all, everything came down to the employees. For nearly 20 years, Frontier Village implemented an elaborate, borderline-compulsive strategy of employee operations—a component many to this day claim was the reason for the park's success.

Customer service was certainly at the top of the totem pole at Frontier Village. If a boy's ice cream fell off the cone and onto the ground, an employee was right there to replace it for him. If a girl lost her balloon, she would get a new one. Visitors didn't have to go a customer service desk and wait for the manager to come down and assess the issue. No one had to wait through a frustrating phone tree before talking to a live human being.

The employee manuals were thorough, and included guidelines for personal grooming, customer interaction, uniform care, and even scripts for various characters and other positions at the park. Many of the Frontier Village staff adopted Wild West personae and took their work seriously. And yet, at the same time, it was all play. As a result, visitors felt safe, secure and clean. It was like stepping into a magazine ad.

Zukin took a hands-on approach with his employees—teaching them everything he knew about business. Everyone was treated equally, as if part of a family. The park taught so many people about life itself. To this day, many former employees say the lessons they learned working under Zukin helped them become leaders in their respective adult professions.

"Joe handpicked a special management team and the core group stayed together for most of the park's history," Weitzel says. "And a key element was that Joe took the egos out of park operation. If someone had a good idea, we embraced it, even if the idea came from a newly hired ride operator. No other department or person was more important than another. And the guests picked up on that ambiance."

As a result, especially in the early years, Frontier Village became one of the most lucrative local places a young person could work, as fast food restaurants were not yet ubiquitous. Young adults fought tooth and nail for one of the 350 jobs Frontier Village offered each year.

"You either worked at the cannery," Weitzel recalls, "or you worked at your mom and dad's business, whatever that was, or you worked at Frontier Village."

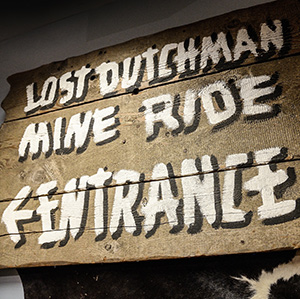

LOST DUTCHMAN MINE RIDE: One of the famous rides in Forgotten Frontier.

LOST DUTCHMAN MINE RIDE: One of the famous rides in Forgotten Frontier.

When Long set out to curate this show, she had no idea what she was getting into.

To this day, thousands of people seem to harbor an intense emotional attachment to all things Frontier Village. Each year, a reunion with the tongue-in-cheek fervor of a Civil War reenactment takes place. The "Remembering Frontier Village" Facebook page boasts more than 12,000 members. And Weitzel claims that 200-plus individuals met their spouses while working at the park.

"What started out as something I thought would be a really fun, kind of kitschy, pop-culture exhibit, has actually been an insane Pandora's box of much greater depth—in terms of people's attachment, collective memory and nostalgia," Long says.

As Long continues talking, she takes on the tone of someone in disbelief. Her voice rising, she recalls attending one of the Frontier Village reunion picnics. "There were probably more people at that picnic than my high school reunion," she says. "These people worked there 35 or 40 years ago and they're still friends. People have saved all these items. They're collectors.

Everybody's saved their scrapbooks and all their photos. They have their uniforms. They have their pins. They have everything."

To understand why these three parks were so important to so many people, it is helpful to understand the context in which they emerged. Frontier Village, Santa's Village and Lost World are just a few of the myriad theme parks which sprouted all over the country in the decades following World War II.

All of these parks played a major role in redefining the childhood experience in America, according to Amanda Tewes, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Tewes is researching the intersection of history and memory in the context of California. In particular, she's interested in theme parks.

"This was the postwar world," Tewes says. "The era was really important for car culture and finding family entertainment."

The life of Frontier Village—from 1961-1980—bookended a unique era in the South Bay. During those years, San Jose's population grew from around 200,000 to 600,000, and yet, as Tewes notes, a small town feel endured.

LOST BUT NOT FORGOTTENAs the excitement over "It Takes a Village" continues to mount, some are convinced that the memories of Frontier Village will live on in perpetuity.

Says Weitzel: "I worked in the amusement industry for 45 years, my brother for 49 years, and managed at several parks, consulted for many more, and the only park anyone ever wants to talk to us about is Frontier Village."

Others claim it's just plain old nostalgia. If the park were still open, no one would need to remember it so fondly. And if happy childhoods really did exist at one time, then why not celebrate?

"I don't think it's a coincidence that because the park is closed, it has such a fond following," Tewes says. "I think, 35 years on, people are able to reconnect with their childhood by remembering Frontier Village at that time, which connects to San Jose at that time, which connects to their lives at that time, and all those pleasant memories combined create a really strong sense of a really wonderful place to be. And a wonderful childhood."

Whatever the case, Long is sure of one thing: those who had any kind of connection to these theme parks in the past are positively psyched about "It Takes a Village."

"Anytime I mention Frontier Village or Santa's Village, everybody gets excited," she says. "Everybody's eyes get big. They get all excited and say, 'I can't wait to see it. I can't wait to see it.'"