home | metro silicon valley index | news | silicon valley | news article

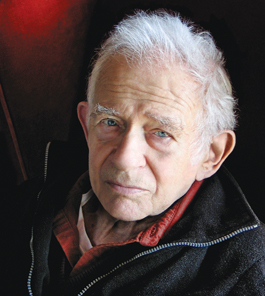

Photograph by Christina Pabst/Courtesy Random House

Tough guys write: Norman Mailer

Norman Conquest

Norman Mailer put an indelible stamp on American life and letters

By Gary Singh

IF EVER there existed a public figure who necessitated a "choose your own obituary" reality show, Norman Mailer, who died Nov. 10 at age 84, would be that person. Drum roll please: He drunkenly stabbed his wife after a party in 1960. He head-butted and punched out Gore Vidal. He helped convicted killer Jack Abbott get out of prison, only to see Abbott immediately kill again. During his 1969 mayoral bid, he suggested that New York City become the 51st state. He constantly blasted the women's liberation movement and championed machismo as an existential force of the ignored and the downtrodden in society.

All in all, Mailer married six times and left us with nine kids and 10 grandchildren. Oh, and he also won two Pulitzer Prizes, the first for Armies of the Night, about a 1967 protest against the Pentagon, and the second for 1979's The Executioner's Song, a real-life novel about convicted murderer Gary Gilmore. The former contained the subtitle "History as Novel, the Novel as History," and both books fall into that category. As such, he was one of the first grandstanders for what came to be called the "New Journalism" movement in the '60s, that is, the author placing himself first and foremost into the fray and booting aside the fallacy of true objective reporting—a guiding principle of alternative journalism ever since. Mailer was among the founders, in 1955, of one of the original alternative weeklies, the Village Voice.

And when it came to overdone belligerent-on-purpose celebrity grandstanding, Mailer practically invented the form. His first novel, 1948's The Naked and the Dead, one of the best narratives to come out of World War II, catapulted him to stardom at age 25, and he never left center stage afterward. For decades, his detractors wished he would just finally go away and shut up, but he never did. He just needed to be heard and heard again, even if he was making no sense whatsoever. He had an opinion on everything and used every medium at his disposal to throw that opinion directly in your face, even if he made a bloody fool out of himself in the process. He was ambitious with a capital 'A,' and he would write about any subject, whether he was qualified to or not, and as a result he cranked out some of the best and worst books of his generation. (His last novel, a fictional account of Hitler's youth, A Castle in the Forest, was published just this year by Random House.)

Perhaps Gore Vidal, a longtime pal and adversary, deserves the last word about ol' Norman: "Mailer is forever shouting at us that he is about to tell us something we must know or has just told us something revelatory and we failed to hear him or that he will, God grant his poor abused brain and body just one more chance, get through to us so that we will know. Each time he speaks he must become more bold, more loud, put on brighter motley and shake more foolish bells. Yet of all my contemporaries I retain the greatest affection for Norman as a force and as an artist. He is a man whose faults, though many, add to rather than subtract from the sum of his natural achievements."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|