![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

This Boy's Plan

Did Al DeGuzman really plan to massacre students at De Anza College one year ago? Or was there another plan all along, a plan that came true?

By Alex Ionides

HIDING IN THE STORAGE area at the back of the Longs Drugs on Berryessa Road in San Jose on Jan. 29, 2001, police waited quietly for 19-year-old Al DeGuzman to return to pick up his photos. Kelly Bennett, an 18-year-old San Jose State University student, was working in the film department that night. She had called police 10 minutes earlier, 24 hours after DeGuzman had dropped off his film for one-day processing.

Police didn't have to wait long. At around 6:15pm, a red '91 Chevy Blazer pulled up to the store, and DeGuzman stepped out. Bennett was back in the warehouse with the officers when DeGuzman, a small-framed, shy-looking young man with short-cropped hair, approached the counter. Officer Paul Hamblin of the San Jose Police Department, watching on surveillance equipment, recognized DeGuzman first, telling Bennett that the man who just entered could be the one from the photos.

A nervous Bennett approached the photo counter, not at all convinced the man was in fact DeGuzman. But then, stepping forward, the young man offered his receipt. After taking the piece of paper and glancing at the name, Bennett walked by her co-worker, Michelle Houde, and the look on Bennett's face said it all. Houde asked Bennett, in a whisper, if she wanted her to go and tell the police. "Yes," Bennett anxiously whispered back.

Bennett stalled DeGuzman, while Houde went to get Hamblin and officer Cassandra Lansberry. The officers emerged from the warehouse, and when they were within 15 feet of DeGuzman, he glanced in their direction, then turned and quickly walked away down one of the aisles.

Hamblin said that DeGuzman was walking too fast and had covered too much distance to hear his call of "Sir," so the officer walked down a different aisle and neatly intercepted DeGuzman. After a quick pat-down, Hamblin escorted him to the back of the store. Court transcripts indicate DeGuzman was cooperative and went quietly. An hour later, he was taken to the police station.

The Bomb Squad

Within hours, DeGuzman's middle-class San Jose neighborhood had undergone a transformation. Police conducted an evacuation of the surrounding homes, asking residents to go stay with friends or relatives. Then Sgt. Larry Weir of the SJPD, clad in a bomb suit, entered the single-story house where DeGuzman lived with his parents and one of his two sisters, and made his way toward DeGuzman's bedroom. It was 2:30am on Jan. 30, when Weir discovered what he had been looking for: an arsenal of weapons that DeGuzman had posed with in his photos.

Weir found a nylon bag containing 18 propane gas cylinders taped together and a backpack containing approximately 25 Molotov cocktails. There were numerous guns, including a cut-down Ruger 10/22 semiautomatic rifle and, in a guitar case, an SKS semiautomatic rifle, an MDL 98 8 mm rifle and a cut-down 12-gauge pump-action shotgun. A plastic grocery bag contained a number of homemade pipe bombs, each with nails and screws taped to the outside and a red fuse attached.

Police also found what appeared to be detailed plans for an attack at De Anza College. Sitting on a desk on the east wall of the bedroom was a black binder, which according to court transcripts contained drawings, text entries, narratives and timelines for a killing at the school.

The details were meticulous, and they caused enough concern at the Santa Clara County Sheriff's Office to warrant an evacuation of the school the next morning. At 8:30am on Jan. 30, De Anza officials were notified by the Sheriff's Department of the possibility that bombs had been planted at the campus.

More than 10,000 students were told to leave campus immediately. Specially equipped vans from Outreach assisted disabled students. Fifty children were evacuated from the Child Development Center. Traffic on De Anza Boulevard and nearby highways 85 and 280 ground to a halt from the sudden influx of vehicles. By 10:30am, De Anza College had been completely cleared, paving the way for FBI, ATF, SERT (Special Emergency Response Team) and SWAT teams to comb the grounds.

No bombs were found.

In the days that followed, the vigilant Kelly Bennett became the valley's heroine, appearing on local news channels to describe her concerns and her timely call to police. She was also flown across the country for appearances on Good Morning America and The Today Show.

Bennett's response, police and officials said, saved countless lives. If it hadn't been for her quick thinking, they said, DeGuzman's plan for a mass murder would not have been thwarted.

After police had pored over his journals and website and the yellow stickies allegedly detailing his plan, Al DeGuzman became known internationally as the "De Anza bomber."

What was not said by police, reporters or school officials is that Al DeGuzman's real plan may not have been thwarted at all.

In reality, Al DeGuzman may have had an agenda very different from the one reported in the press.

Life Inside

One year later, DeGuzman awaits trial in his cell on the seventh floor of the Santa Clara County Main Jail. The elevator takes visitors directly to the stale-smelling booths with the phones and the thick glass dividers. There is a small glass window on the door behind the inmates' side, but it does not reveal much of life at the jail. Guards stroll by every few minutes to peer in.

Facing more than 110 charges of possession of a destructive device and possession of a destructive device with the intent to injure persons or personal property, DeGuzman could receive a sentence of more than 100 years. Police and prosecutors believe the evidence indicates that his arrest came on the eve of an intended massacre at De Anza College on a par with the one at Columbine in April 1999. Several months ago, he agreed to an interview with this writer, who was working for the De Anza newspaper La Voz.

Dressed in the red shirt and orange pants reserved for inmates under the highest security, DeGuzman looked pale and relatively thin. He had a lethargic look in his eyes but was sharp and clear when he spoke. With his baby face and a uniform that hung on him like pajamas, he seemed more fit for a slumber party than a jail cell. His left hand was chained, but his right hand was free to handle the phone.

On strict advisement from his attorney, Craig Wormley, DeGuzman remained tight-lipped about his case, deflecting any questions specifically about the event with a gentle raising of his right hand and an apologetic "I can't answer that." He was calm and soft-spoken, and made sure that the questioner was finished before offering a reply. He said that he has no history of violence, had never been in fights and was never bullied. This is his first arrest. He looked resigned to his fate.

"I've changed a lot since I've been in jail," he said. "When you are in here, you have no passionate response to anything. You lose all feeling. Now I just think about freedom."

Following his arrest, DeGuzman was diagnosed with "major depression." He said he became aware of his condition at age 15. "That's when my grades started to go down. The depression was on and off, and lasted until my arrest. In some ways, the arrest was good. It helped me deal with my depression."

He's thought about suicide many times since his depression began. "There was a lot of crying, for no reason.," he recalled. "Everything you think about when in depression, you just put through this mental filter. Everything is negative."

"They put me in mental health when I first came in. I was on suicide watch," he said of the ward where he was kept with other prisoners who have mental problems. "It's really tough in there."

DeGuzman said he now takes the antidepressants Paxil and Wellbutrin. "I feel better now. The volume on the negative thoughts and self-hate is turned down." But DeGuzman was reluctant to label himself a mental patient. "I wouldn't call it a mental illness."

His parents moved to America from the Philippines in 1968, and DeGuzman was born and raised in Santa Clara County. In elementary school, he was almost put in a school for gifted children, but recalled that he opted out because he "didn't want to go."

DeGuzman lived in the family's San Jose home with his parents and two sisters since 1986. He said he never told his family about his depression, and that while growing up, his relationship with his parents could not be classified as close. "I never really talked to them much. We didn't fight or not get along. It's just that as long as I gave the air of normalcy, they left me alone--as long as I kept my grades up and that sort of thing."

He said that the arrest has had a positive effect on the relationship he has with his parents. "It's brought us closer."

DeGuzman's parents visit him twice a week, but they do not talk about the case. His sisters also visit him.

Before his arrest, DeGuzman said, he had a normal social life involving friends, girlfriends, music and events. "We'd usually just hang out at somebody's house. Go to parties, every once in a while get shit-faced," he recalled with a smile. He said that he writes to his friends often from jail and receives visits from them. "They have been supportive."

And they remain committed to standing by DeGuzman.

Vinh Nguyen expressed fierce loyalty when contacted for comment, refusing to say anything for fear of causing problems for DeGuzman, whom he described as "a very good friend."

La Voz, the De Anza College newspaper, ran an article in its Feb. 5, 2001, issue in which a journalist for the school paper interviewed one of DeGuzman's friends. The friend was quoted as saying, "Me and all of Al's close friends know he wouldn't have done it. Anyone who ever truly knew Al knows that he would never do such a thing. He would never endanger human lives."

Creative, Intelligent

Paul Ender was the yearbook adviser at Independence High School while DeGuzman was on the yearbook staff. In his senior year, DeGuzman was one of five editors on a staff of 90 who met everyday during school and sometimes stayed up until 2 or 3am on deadline days.

Ender, now retired and living in Vancouver, Canada, describes DeGuzman as intelligent and cooperative. "He was self-driven. He took the responsibility upon himself to make his year's book better than the previous year's. He was the driving force behind not settling for second best."

When DeGuzman graduated in 1999, the Independence High School yearbook won the JEA/NSPA Pacemaker and CSPA Gold Crown awards, which Ender described as the "high school press equivalent of a Pulitzer Prize."

DeGuzman was one of the stronger leaders on the staff, Ender said. "He was a good leader--very cooperative. The kids respected him. He would not have been editor if he did not work well with other people, cared about what he was doing or cared about others. It was not just my decision [to make him editor], it was a group decision. The program attracted the cream of the crop at Independence. Many of the kids came from the honors English program. They came to me smart."

Devastated by what has happened, Ender was overcome by emotion when discussing his feelings. "I'm still shaken by it," he said through tears.

"One of the unique things about Al is that he would create things. He would take my artist tape and rulers and stuff, and create sculptures and things like that. We would always chuckle about his latest creation."

DeGuzman was not outgoing or expressive, Ender said, but he was friendly. "I would call him on the shy side, but [he was] not afraid to say something or speak his mind. He was a little more introspective."

Ender said that he found media representation of the events troubling. "It's given me a whole new perspective on people that you see on television accused of terrible things. We make a monster out of somebody, and therefore that's what they are forever."

Stickie Business

A sawed-off shotgun, a sawed-off rifle, handguns and more than 50 explosive devices were confiscated from DeGuzman's room in the early morning hours of Jan. 30. But the most damning of the evidence, in prosecutors' minds, is the length he went to detail his plans. Diaries, a tape recording of what he intended to do and maps of De Anza with Post-it Notes stuck to them. Written on the notes were instructions: "Kill supervisors at Campus Center; Kill all at library; Kill fast."

His website, which authorities quickly removed from the Internet after his arrest, will likely be introduced in court. DeGuzman said that he had "many things on the site, but the media chose to take [the negative comments] they wanted. I had a lot of positive things to say."

Police noted DeGuzman's apparent admiration for the Columbine killers. In April 1999, teenagers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 13 people and themselves at Colorado's Columbine High School.

On his website, DeGuzman reportedly wrote, "The only thing that's real is the word of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold--they knew what they had to do to change the world and they did it."

When police rounded up the cache of devices and weapons in DeGuzman's bedroom, they also took with them his journal, some 300 pages of entries and notes. But people close to him believe the last entry, made right before his arrest, is the most revealing.

DeGuzman's attorney summed it up like this: "I am going to take these photographs to Longs Drugstore and get them developed. I am probably going to get caught. Oh, well."

Wormley said that one theory that the defense team will introduce in court is that DeGuzman had every intention of getting caught that night. Because of his experience as yearbook editor, he not only knew how to develop film but had always developed his own film. DeGuzman had "never, ever developed film before at drugstores," Wormley said. By turning it in at a Longs, he maintains, DeGuzman was planning to get caught and was "crying out for attention."

Ann Akers was the San Jose rep at Herff Jones, a yearbook publishing company, during DeGuzman's junior and senior years. She said that she met with the Independence yearbook staff once a week, helping the students put together their book. "You could make a list of kids who might not make it to adulthood, whose tempers might get them into trouble or who might scam someone and get caught at some point," she recalled. "Al was none of those kids. He was a great kid."

Akers said that DeGuzman was a quiet leader and an excellent team player. "He was insistent about standards and was equally insistent that this was a group project. He did not feel that this was his project or that it had to be done his way. It was important to him that the kids got along and had fun. You could be the smartest kid in the room and supercreative, but if you weren't able to work with and motivate other kids, there's no way you could be editor."

Like Ender, Akers couldn't believe the news about DeGuzman's arrest. "When I first heard it, I said this was not even possible," she recalled. "There is no way he was ever going to do this. No way. I can only think it was like a challenge or contest.

"Every yearbook kid knows there is a human standing at the [photo development] machine. Al was very intelligent. He is one of smartest kids I have met. When he took the film [of the arsenal] to be developed, he was turning himself in. He was saying that he proved he could do it, and now it's over."

Acknowledging the possibility that DeGuzman might spend decades, or possibly the rest of his life in prison, Akers was clearly agitated. "It makes me sick. I believe I know that he wasn't going to do it."

Media Monster

Following his arrest, DeGuzman took a beating at the hands of the media. Headlines included "Vanity Helps Nab a Prospective Killer" (ABC News); "Photo clerk says California bombing suspect was 'weird' " (CNN); and from the San Jose Business Journal, "Store clerk credited with averting mass murder."

DeGuzman is concerned and upset by how he has been portrayed. "How could [the media] judge? Nothing came out of anything that the police were saying. It was really subjective, as they were trying to come up with some conclusion." He said that "in some ways" he feels like a victim, as he has been labeled by the media as "the guy that was going to blow up De Anza." He has little respect for mainstream media. "So many times there is just no support for their arguments."

In September of last year, DeGuzman reached out to the students and faculty at De Anza College by writing two letters to the school newspaper. Following the publication of the letters and De Guzman's senior picture on the front page, the staff at La Voz received a beating of their own.

Martha Kanter, the president of the college, wrote a letter to the paper that was subsequently published. She blasted those responsible for what she called "extremely poor editorial judgment that reflected equally poorly on the newspaper and the community at large" and requested that the paper apologize to the "victims of Mr. DeGuzman's actions and [those] who were terrorized by his actions."

La Voz offered no apology.

The purpose of writing the letters, DeGuzman said, "was to find out what people [at the college] were thinking. All these people showed up at my preliminary hearing, and they looked [so angry]. They looked like they wanted to kill me."

In the letters, DeGuzman offered his address at the jail if anyone wanted to write to him. "I wish to present the opportunity for De Anza students, and all those interested, to express their thoughts and feelings to me directly," DeGuzman wrote.

"The decision to do so came about just today [Sept. 13, 2001] while entering court for my preliminary hearing. I was met by the disdainful and angry faces of those students who happened to be in attendance. This made me realize that I still have not come to a conclusion of the general consensus among any affected individuals regarding my arrest and current case--all letters will be answered and no views of the author will be considered too extreme."

He ended each of the letters with jocular postscripts about "how damn boring jail is" and how males fearing "ass peril" have nothing to worry about, as the showers accommodate only one person at a time.

Charles Ramskov, a psychology instructor at the college, made no attempt to hide his disgust with La Voz's decision to publish DeGuzman's letters. In a letter to La Voz, Ramskov suggested that DeGuzman was "attempting to gain court favor" and that the school paper played into his hands.

"I mean, what's next," Ramskov wrote, "a candlelight vigil and speeches about how he was victimized? Why not a bin Laden picture and letter campaign for the next issue."

In a tit for tat, Ramskov wrapped up his letter with a postscript of his own: Rebutting DeGuzman's "ass-peril" comment, Ramskov wrote "DeGuzingman might have more luck with the showers at the federal prison."

Comments from students were mixed, with some suggesting that DeGuzman had a right to be heard, and others expressing their resentment at La Voz. One month after the letters were published, DeGuzman said that only one person wrote to him.

Terrorist Times

Securing an unbiased jury might be difficult considering media coverage so far and the fearful state of the nation after the events of Sept. 11. Wormley, DeGuzman's attorney, is concerned about much of what he has seen in the media. "Apart from some good pieces, it's been horrendous. I think they portrayed him as an absolute monster. I can see it both ways, but I'm not happy with [most of what I've seen]."

The trial, originally set to begin in mid-November last year, was first postponed until Jan. 22 and has been postponed once again. Wormley said the reason for the delay is that the defense's explosives expert, who is out of the country, is needed to review the devices and prepare a report for the defense team.

He added that the defense has "a difference of opinion over the devices" that the district attorney and the law enforcement agencies have. "I think that they mistakenly believe that all of the devices are explosive devices, and we disagree".

The trial will now likely begin in February, Wormley said. "The judge isn't going to give us much more time [to examine the devices]. We're looking at maybe an additional 30 days."

The prosecutor in the case, Santa Clara County Deputy District Attorney Tom Farris, said that jury selection might take longer than usual. "[This case] has engendered a lot of publicity both here and elsewhere. Given not only the historical events that are similar in nature, but also the recent events of Sept. 11, I think that in particular, the defense would be very cautious in their approach to selecting a jury."

The events of Sept. 11 are "absolutely a big concern," Wormley said. "It is a concern for a lot of defense attorneys now."

A plea bargain has so far been ruled out, and Farris said that it is unlikely to happen at this stage. "The defense would have to be willing to satisfy a high number of years."

Wormley said that the two sides are not even close to striking a deal. "We thought that we presented a pretty good faith offer to the district attorney's office, and without giving any numbers whatsoever, I can tell you that we're way off in terms of what we want and what they want."

The prosecution will likely come down hard on DeGuzman. The evidence is overwhelming, and even DeGuzman acknowledged that he "seems to be up shit creek, without a paddle."

Farris said that the district attorney views the case as an "extremely serious situation," and that evidence "suggests that DeGuzman had a hero worship for the Columbine killers. The evidence supports that he intended to use devices to kill as many people as he could."

But according to Wormley, DeGuzman's actions were just a fantasy for him. "That's been our continuous perspective of this case. We're not deviating from that. I'm of the opinion, our defense experts are of the opinion and our co-council is of the opinion that Mr. DeGuzman, all along, wanted to get noticed or get some attention that he may or may not have been getting." Wormley acknowledged that DeGuzman's attempt to get attention was "very unreasonable," but that he had "absolutely zero intention of carrying out this particular mission."

The Trap Door

Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wis., offers a course called The Psychology of Fantasy and Imagination, taught by Anees Sheikh.

"There is such a thin line between where fantasy stops and reality begins," Sheikh said. "In some cases, doing this stuff in our mind kind of acts as a catharsis. Then you don't have to do it in reality. One way of looking at it is the Freudian way, or wish fulfillment. It kind of takes care of some of your frustration. You can't do it in reality, so at least you can do it in your mind."

Sheikh also said there's another way to look at it. "Practicing in your mind may make it easier for you to do the same thing in reality. So if you use that argument, a person who is practicing the murder in his or her mind might, in a way, be more likely to carry it out."

J. Reid Meloy, a forensic psychologist and an associate professor of psychology at UC-San Diego, was an expert witness for the prosecution in the Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols cases. Meloy said that it is possible that DeGuzman's trip to the drugstore was his way of turning himself in. "It likely indicates that he had some ambivalence or conflict about what he was [planning] to do."

Meloy said that DeGuzman's actions might have been an attempt to "turn over control to someone else." But Meloy also said that if DeGuzman was not caught, "it is highly unlikely that he was not going to carry out this act. If it was just a fantasy, it would have remained a fantasy. He wouldn't have amassed that kind of weaponry."

Diane Schetky, a board-certified child, adult and forensic psychiatrist, who evaluated Michael Carneal after he killed three girls at the Paducah, Ky., high school he attended in 1997, also believes that it is more likely than not that DeGuzman would have gone through with his plan. "[DeGuzman] wouldn't have amassed that kind of weaponry if it was just a fantasy. Recurrent fantasies can be risky, because if you keep rehearsing them it can be easier to act on them. It's like a dress rehearsal for the play."

"Knowing whether [someone] is actually going to stay at the fantasy level, or whether this fantasy is going to be kind of a practice for you to do the same things in reality, we cannot tell," Sheikh said. "We'd have to look to see if he or she has some history of indulging in elaborate fantasy or imaginations, but never went beyond that."

Larry Faison has a Ph.D. in child and adolescent psychology. He has his own practice and works for the juvenile courts in Daphne, Ala. He said that when someone is suffering from major depression, "differentiating between fantasy and reality is a very hard thing to do. It has to do with the buildup of serotonin in the brain."

According to Faison, there is typically a social factor that precipitates the event: "A social snubbing. The girl of your dreams gives you the shaft; you didn't get into the university of your choice."

DeGuzman said he missed getting into several universities "by like .001 percent." Accompanying one of the photos he sent to La Voz along with his letters, was a note reading, "I'm pretty sure this was in Arizona ... but anyway, that's me, and my two sisters, Minda and Leah. Taken during a cross-country trip across America from San Jose to NY. Before leaving, I received six rejection letters from various colleges--apparently being 0.001 points short of a qualifying GPA makes a big fuckin' difference. My clinical depression was at one of its most intense points during that summer."

Facing the Future

In his time at De Anza, DeGuzman majored in sociology. He enrolled in classes, including Intimacy and Marriage Today, and Social Problems. From his cell awaiting trial, DeGuzman said he would like to continue his education in history and social studies, and one day get a teaching degree. He wants to get started on his plans while in prison. "I hear if you have some kind of skills, they let you teach [the other prisoners]."

He added, "After being in here for two months, I decided I was never going to get in trouble again." "The hardest part about being in here is that you are just wasting your time. I feel like everything is on standstill. I just try to take it day by day."

Sometimes he dreams, he said, of having a family, of moving to a less crowded place. "Moving away from here."

He admitted that he is scared about going to prison. "What can I do?" he asked matter-of-factly. "I'm facing any fears I have."

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

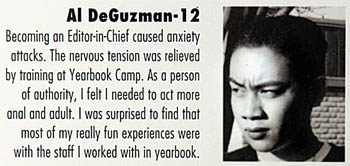

Timed Exposure: DeGuzman's High School yearbook statement hints at his struggle with what would. when he was incarcerated, be diagnosed as clinical depression.

Hard-Pressed De Anza College's weekly newspaper 'La Voz' caught flak for running letters from DeGuzman, who requested that students write to him in jail. He received only one response.

Hard-Pressed De Anza College's weekly newspaper 'La Voz' caught flak for running letters from DeGuzman, who requested that students write to him in jail. He received only one response.

From the January 31-February 6, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.