![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Unmasked Society

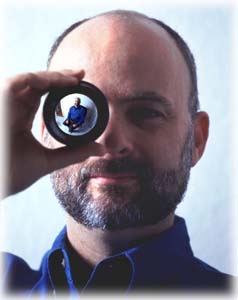

Photos by Christopher Gardner

Science-fiction writer David Brin worries about the future of privacy and advocates more, not less, openness as a solution

By Zack Stentz

EACH TIME bank customers withdraw money or check an account balance at an Automatic Teller Machine, their photographs are taken and stored in a computer. This goes on in the name of preventing robberies, something few would argue with. But what about the cameras down at the department store, keeping an eye on potential shoplifters at the same time they let unscrupulous security personnel ogle folks trying on swimsuits in dressing rooms? A reasonable compromise between security and privacy?

Then try this near-future scenario on for size: a security camera on every lamppost, watching over all of society, whether running traffic lights, scratching rear ends or cheating on spouses, along with a swarm of tiny, undetectable robot drones flitting through the air, peeking over walls and into darkened windows with enhanced infrared vision.

Like it or not, this Argus-like world of a million unblinking eyes is on its way, according to author David Brin. "The only thing accomplished by privacy laws," Brin says, quoting from Robert Heinlein's classic science-fiction novel Stranger in a Strange Land, "is to make the bugs smaller."

And Brin ought to know. As a bestselling science-fiction writer himself (Earth, Startide Rising, The Postman), Brin gets paid handsomely to look into the future and report back on what he's seen. In his nonfiction book-in-progress, The Transparent Society (bits of which have been excerpted in Wired and other publications), the author examines a future where privacy and anonymity have been rendered obsolete by technological change.

Brin on science fiction, society, and Kevin Costner

But Brin, who differs from pro-privacy activists and encryption advocates who decry the shredding of secrecy, views the loss as an opportunity as well as a threat. If privacy is history, he asks, why not build instead a future of openness, trust and mutual accountability based on the free two-way flow of information?

In some places, according to Brin, the future has already arrived. "In Britain today, nearly every city has put up hundreds of video cameras in public places, connected to the police stations," he says, "and the public loves them, because crime and hooliganism have plummeted every place that they've been put."

Appropriately enough, the technology to implement this watched world is being perfected in Silicon Valley. Recent media reports have hailed the potential of the microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), under development at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center, to perform a variety of useful tasks.

One role promoted for MEMS in a 1995 report by the Pentagon's Advanced Research Projects Agency is as "surveillance dust": several thousand microminiaturized camera/infrared-detector/microphone packages dropped via individual parachutes over a battlefield. This "dust" would float like dandelion fuzz for several hours and track a potential enemy's every move. The civilian applications of this technology need scarcely be mentioned.

The Masked Society

LIKE MANY of Brin's other thought-provoking, often contrarian ideas, the thesis of The Transparent Society has already engendered much debate in both the abstracted realm of cyberspace and the real world of policy makers. Predictably enough, Brin's opinions put him at odds with many traditional privacy advocates.

For Beth Givens, director of the San Diegobased Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, a public-interest law firm, the dream of camera-equipped safe streets looks a lot like the nightmare scenario outlined in another famous work of science fiction. "I see nothing on the horizon to stop the Orwellian use of video cameras," Givens warns.

Brin acknowledges the misgivings of the pro-privacy forces and admits to feeling a bit ambivalent himself about surveillance technology. "Critics of the cameras say the inevitable conclusion that one will reach along such a road is Big Brother, because no matter how trustworthy today's generation of police officers might be, their heirs will be tempted to abuse the camera.

"And yet," he adds, "I'm an optimist. The cameras are coming; nothing will stop them. But we might find a better way of using them than is currently taking place in Britain."

To alleviate the ills that come with the fishbowl existence of the future, Brin proposes that we adopt a family of options he calls Mutual Transparency Solutions--or two-way transparency. "In other words," he says, "let's see if the problem might actually be solved by increasing the flow of information.

"One variation on this theme would be to forbid any power center--the government, police, or corporations--from having monopoly control. Instead, the power of sight goes to everybody."

Givens, though, finds this specter of neighbor spying upon neighbor nearly as frightening as that of the government and large corporations using surveillance technology. "I just don't see it [two-way transparency] as being practical," she says. "It assumes a society much more tolerant than the one in which we live."

The two-way transparency solution also has the effect of destroying the culture of anonymity so cherished by nuclear-family Americans, the culture that allows us to live our lives largely free from fear of reproach from judgmental neighbors, a state of affairs Brin likens to mask-wearing. But while concealing one's identity might work fine for the Lone Ranger, Brin views it as a feeble defense against the predations of government and corporate power. "No one can come up with a single example in human history in which a society's overall freedom was increased by the propagation of masks, chadors and armor plates," he asserts.

And the social downside to this constant wearing of various "masks"--some legal, some electronic--to guarantee our privacy is also becoming apparent; one need only look at the Internet, where the safety of hiding behind a clever pseudonym and text-only interaction brings out a whole range of antisocial behaviors from the people Brin calls "Net tourettes."

"Anonymity has terrible costs," Brin contends, ticking off examples. "The cruelty and loneliness of modern urban life. The locks on our doors and fear of masked assailants. Nor is anonymity even the best defense against cruel gossips. No mask ever worked as well as the flashlight.

"The Golden Rule is normally preached as a lovely little morality tale. But it could be looked on as a much more militant lesson about both courtesy and freedom. In fact, gossips, dictators and all manner of tyrants rely on two preconditions to do harm. First, an ability to meddle in the affairs of others. But even more important, they must prevent others from seeing them!"

Before he can be pressed for a specific example, Brin posits a quiz: "Which of the following would have stymied Hitler? Some old Weimar law officially protecting his victims? Or a preemptive exposure of every dark secret within the Nazi Party? Hint: the technique we have used, to remain free, has always been relentless enforcement of accountability upon the mighty."

Givens remains unconvinced, though. "Two-way transparency doesn't work on people who think they have nothing to hide but feel comfortable policing the behavior of others," she says.

Watching the Watchers

IS THIS WORRY over widespread surveillance and information dissemination anything new? "Not really," answers Dr. Willis Ware, a privacy expert at Santa Monica's Rand Corporation and organizer of several congressional hearings on the subject in the 1970s.

"Technology is forcing us to deal with questions that have always existed," Ware says, "but haven't been as important until now. We've always been able to watch each other.

"I think Dr. Brin's solution should be one idea out on the table," Ware adds. "But there are other possibilities as well, like giving people the right of ownership over their personal information."

And Brin cautions others not to interpret his position as stemming from some deep-seated hostility toward the notion of privacy and anonymity. Walk past the Brin family bedroom at night, and no doubt the blinds will be drawn.

"Personally, I adore privacy," he sighs. "I enjoy my ability to be anonymous. But lately, I've noticed that each time a problem about the modern information age comes up, the knee-jerk response is to suggest shutting down the data flow somehow. Passing laws to restrict access, setting up barriers, sanctioning people and institutions for knowing things. Yes, this may be necessary at times. But it's a lousy habit to get into without at least sometimes considering other choices."

Brin offers an example to bolster his point: "Say a company is trying to gather the phone numbers of every citizen. Instead of passing a law forbidding this, which in the long run will prove futile, we might instead require that every corporation collecting such data must openly publish the home numbers of its top 50 officers."

"I like that solution," says Terry Francke, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition. "If a telemarketer calls me up at home, I'd sure like to have the pager number of the company's CEO to call him up and let him know how I feel about being interrupted."

And as for a camera-filled society, Brin spins out a more positive possible future, one already hinted at by the real-life furor surrounding the videotape of the Rodney King beating. "Imagine how the social climate of our inner cities will change," he says, "when both the cops and ghetto youths carry around cheap little shoulder-mounted TV cameras, monitoring their encounters in real time. Conviction rates may go up, while illegal rousting and hassling of the innocent will certainly go down. Accountability goes both ways."

Brin's on such a roll it seems a shame to point out that cameras only have power when accompanied by the political and social will to act on the information they record. Despite the infamous King videotape, the Simi Valley jury still acquitted the accused officers.

"My point isn't that these are ideal answers to modern problems," Brin says, "but that this entire family of solutions is almost never tried. Instead, everyone talks about shrouding information, blocking vision, creating new layers of secrecy."

Cypherpunks

ONE OFT-PROPOSED new layer of secrecy is the spread of cheap, readily available encryption technology to computer and phone users. The ability to encrypt one's own information is advocated by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and so-called cypherpunks as a remedy for the proliferation of electronic monitoring by governments, corporations and individuals. But this solution, a nearly precise inversion of the old hacker notion of unlimited access to all data as an ideal state of existence, doesn't impress Brin either.

"Solution to what?" Brin asks rhetorically. "The cypherpunks and other encryption junkies contend that freedom will be guaranteed by providing the little guy with masks he can wear. Freedom does not work that way. The one prerequisite of freedom is the ability of the common person to deny masks to the rich, the powerful or a bureaucratic elite."

"Well, I certainly like the last part of that statement," says Jim Warren, a Woodside-based technology writer who refers to himself as "firmly on the fence between privacy and access. It's barbed-wire and very uncomfortable."

While agreeing with Brin that greater openness is essential and desirable in many situations, Warren supports the adoption of cyphers and scramblers on phones and personal computers.

"One of the characteristics of modern cryptography," Warren says, "is that the codes today are different than anything we've had in the past. Unlike armor or masks, they're not penetrable, and they're comfortable to use. We could have privacy of communications and personal data on our PCs, if we had national standards; but the government won't allow it, because they want to be able to monitor and pursue the tiny minority of people who they suspect of using this technology to break the law."

But as befits his background as a science-fiction writer, Brin points out a technological reason why he thinks encryption won't work: microminiaturized cameras, watching every computer keystroke as the user enters his or her secret password.

In the end, though, Brin views the fetishizing of cyphers and codes as guardians of individual freedom as a distraction. "It's all about accountability," he declares. "If we're a free people, we will have some privacy. We'll be able to openly debate how much privacy to vote ourselves. But the one thing that freedom needs to survive--and without which it must fail--is accountability. In other words, the answer is not masks. It is light. Not armor plate, but the light saber."

Society's Pendulum

THE SUBJECT of privacy and its discontents has long been a favorite philosophical battleground for Brin. In Earth, he imagines a society a half-century from today in which privacy and secrecy are not only technologically impossible but scorned and morally suspect as well.

"Generational fads tend to pendulum," he says of his fictional speculation. "Ours is now heavily into personal anonymity and indignant self-righteousness, which will cause immense problems over the next 20 years.

"One can even imagine a radical generation coming along--kids being born now--who will perceive secrecy as the root cause of human evil. In Earth, I depict that generation having won, and the pendulum then swinging back, as their children rebel. In fact, I'm not a radical in either direction. But I do see today's universal mania of privacy fetishism needing a little balance."

Brin's espousal of openness and corporate accountability also put him at odds with the "techno-libertarian" ethos so prevalent among other science-fiction and technology writers such as George Gilder and techie organs like Wired magazine.

"Today, we have as many bright young libertarians who believe passionately in the mystical power of the market as [there were] bright young college graduates transfixed by the persuasive mantras of Marxism in the 1930s," Brin says. "Each generation has to learn the hard way that no ideology can describe complex human beings, who are both cooperative and competitive by nature."

In a similar vein, it would seem that the tug-of-war between privacy and openness needn't be an all-or-nothing matter, at least not in a society where citizens clamor for "call return" features on their phones (a perfect real-world example of Mutual Transparency) while simultaneously asking to have unlisted numbers.

"When given a choice between privacy and accountability," observes Brin, "most people tend to choose privacy for themselves and accountability for others."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

The Cost of Anonymity: The desire to hide behind legal and electronic masks can sometimes lead to a whole range of antisocial behaviors, says Brin.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the February 6-12, 1997 issue of Metro