![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Bits, Bytes and Bullets

San Jose director Pete Anderson uses the latest in digital high-tech to create a low-budget heist drama

By Jim Rendon

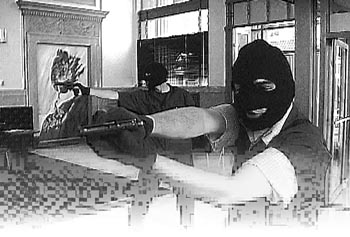

THE DOORS to a Sunnyvale A&W swing open. Two men--one wearing a hockey mask; the other in a basset-hound mask, bright red tongue dangling between cheery plastic jowls--burst into the restaurant. They pull pistols and demand cash from the tiny woman at the register.

Nervously, she fumbles with the drawer while one of the robbers levels his gun at her head. The men anxiously scan the glowing orange booths full of terrified customers as the woman hands over a fistful of bills. The two intruders turn and run, a few hundred dollars richer--and one stick-up closer to their demise.

As they reach the restaurant doors, an unassuming man working a tiny tripod-mounted camera stops the crime spree in its tracks with a simple wave of the hand that signals, "It's a wrap." This slice of urban violence is part of Hope, a tale of brotherly devotion and desperation by 30-year-old San Jose filmmaker Pete Anderson.

Watching a montage of Hope's heist scenes play on his computer monitor, Anderson fidgets. His hands, nearly as white as his keyboard, move quickly between his beeper, his phone and his computer as he nails down his final edit and calls in some favors. In the last few months, Anderson has rarely left his editing box at the back of a glorified storage unit in Sunnyvale. After all the location shooting is done, filmmaking is mole's work.

Anderson's movie (which screens Feb. 26 at Cinequest San Jose Film Festival) redefines low-budget filmmaking. Thanks to the latest technology in digital cameras, the A&W scene was thought up, laid out, rehearsed, shot and deemed a success in less time than it takes Steven Spielberg's crew to track down a decent latte.

Digital technology is so cheap--so versatile--that it encourages a kind of creative serendipity that traditional directors working with bulky 35mm cameras gave up decades ago. The A&W scene, for instance, wasn't originally in the script for Hope. Anderson and his small crew had stopped at the restaurant to grab a quick dinner before filming a robbery scene at a nearby liquor store. But one look at the A&W's gleaming orange '70s interior and cinematographer Toshio Omori knew he had to shoot there.

"We asked the girl at the counter, and she said, 'OK,' " Anderson recalls. "We grabbed the masks out of the car and threw the whole scene together in 10 minutes."

Ground Zeros and Ones

DIGITAL CAMERAS are to analog video recorders and film cameras what recordable CDs are to cassettes. The image--the visual information transmitted by the lens--is digitized, turned into zeros and ones that can be manipulated by a computer. The cameras are light and easy to use; the tapes are small, durable and, best of all, cheap: an hour-long digital videotape costs about $15. By comparison, four minutes of 35mm film, after processing, costs about $600.

Anderson shot 20 hours of tape to make his two-hour movie, recording whenever he felt like it. If he had been working in film, Anderson says, he would have shot maybe eight hours, tops.

"With video, you can fuck around and improvise, change things on the fly, waste a lot of tape," Omori adds. "With film, there is no room to fuck up. The director's stress can kill creativity. All you think about is getting it shot by the end of the day."

With the advent of digital cameras, the cost of the tools required for the rest of filmmaking has also plummeted from the million-dollar ballpark to a $10,000 neighborhood. A Macintosh G3, a digital sound unit and some software can turn out professional-looking movies. It doesn't take a degree in accounting to understand why Anderson and other independent filmmakers are so excited.

"It's perfect for guerrilla filmmaking," Anderson says, waving the Kleenex-box-sized digital camera around with one hand.

In the 1980s, laser printers and layout software fomented the desktop revolution in publishing. Anybody with more opinions than money could suddenly play William Randolph Hearst. Then came the web, and thousands of e-zines blossomed. The same phenomenon is giving the big record companies fits: Any kid with a demo tape and a computer can distribute his music on the web for free.

Slash the production costs, and the number of producers will mushroom. Filmmaking is no exception. Minuscule digital production costs have the potential to entice people who never thought of making movies before. New voices and ideas will make their way into pictures. At best, this could lead to a renaissance in filmmaking, pushing everyone to new heights. At worst, a million Tarantino wannabes will be filming shootouts on every street corner in America. Like the web, the new technology will invite a burst of independent creative energy, and as on the web, amid the thousands of porn sites and self-indulgent personal displays, there will be one or two gems of insight and inspiration.

"You don't have to be a trust-fund kid to make movies anymore," Anderson says. "You can spend $20,000 going to school or spend $10,000 and shoot your film tomorrow. If you sit around and think you'll get a couple of million to shoot on 35mm, you're fooling yourself."

Against the Grain

ALTHOUGH DIGITAL VIDEO is still in its infancy, the technology is starting to seep into the mainstream. The Cruise, a digital documentary about a New York City tour guide, earned encouraging reviews last fall. A number of features at this year's Sundance Film Festival were shot on digital video; Hal Hartley's newest will be digital.

But established directors still need to be convinced. Thirty-five millimeter film remains the industry standard. And to most, it will never be superseded by the mathematical approximation of zeros and ones, no matter how finely tweaked. The light-sensitive emulsion on film gives it a textured look called grain, and the 35mm format delivers unrivaled depth and detail. The right cinematographer with state-of-the-art equipment can produce images of painterly splendor.

Gordon Willis dared to shoot interiors for The Godfather bathed in darkness because he knew that the details he wanted would still shine through. On big screens like the one at the Stanford Theater in Palo Alto, an original 35mm print of a Josef von Sternberg film made more than 60 years ago captures the tiniest highlights sparkling behind a piece of lace held up in front of Marlene Dietrich's face.

Nostalgia aside, digital technology has been making inroads into the analog world of film for more than a decade. Since the 1980s, film has been scanned into high-end computers for editing, adding computer-generated special effects and synching sound with the images. Once complete, the whole product was laid back out on film to be shown in theaters.

Shooting with digital videotape streamlines that process. With images digitized, information can be fed directly onto a computer and edited there sequence by sequence. It's a revolution of sorts--although only half of one for now. All these films originate in the language of computers, but they still must be printed on 35mm stock so they can be shown in theaters alongside traditional movies. The emergence of high-quality digital projection systems is still a few years off.

Chip Dreams

IN A TOWERING black sprawl of glass and steel on Zanker Road, Sony is developing the new digital-imaging technology. Laurence Thorpe sits up at the edge of his seat, dwarfed by his wrap-around desk and high-backed chair, extolling the virtues of Sony's digital cameras.

Thorpe, the white-haired Englishman who runs Sony's video division (and is a panelist at Cinequest's Digital Cinematography workshop Feb. 27), explains that digital video owes its existence to the technological leap that engineers first made from film to regular videotape. With a film camera, light travels through a lens directly to light-sensitive emulsion on film. With the advent of video in the 1970s, computer chips were used to convert light into electronic impulses. Then those impulses were recorded on magnetic tape.

But video, even at the high end, was not film. The image looked cheap. Whites glared, blacks had no detail. Although some documentary filmmakers grabbed onto the technology, it had nowhere near the quality necessary to challenge film. With digital, however, more and more information could be collected and transmitted, helping the new format inch ever closer to the quality of film. "Not until the last four or five years did we catch up," Thorpe says.

In the last year, Sony has actually been able to surpass film in one important area. Digital video can now outperform film in some adverse lighting conditions, Thorpe says. When the cinematographer works in both dark and light--shooting into a cave on a bright day, for instance--digital video records more information than film, especially in the dark parts of the frame.

Field Work

ON MONGOLIA'S OPEN steppe and in its cramped cities, Jessica Woodworth found herself reaching again and again for her digital camera. A documentary filmmaker completing her master's at Stanford, she found the new medium's flexibility and high-quality, low-cost equation irresistible.

She was able to maneuver through the crowd at massive nighttime Mongolian rock concerts, capturing great footage in dim light without dragging along a large crew and obtrusive lights. She used digital to shoot what she calls sketchbook shots, to make a record of things she wanted to come back and do in film. Unlike bulky film cameras, digital versions attract little attention, and they proved less intimidating to the young Mongolians she interviewed.

But digital didn't work for everything. Woodworth shot half her documentary on 16mm film. The dramatic Mongolian landscape, with its sharply angled mountains and barren, flat desert, paled on video. "Landscapes don't hold well on digital," she admits. "The image is not as strong. Film is still superior, richer."

Jan Krawitz, director of Stanford's documentary film program, says that digital video may produce another revolution in documentary filmmaking similar to the one in the 1960s. Four decades ago, documentarians were burdened with cumbersome sound equipment that worked best indoors. With the development of the Nagra portable unit, filmmakers were free to shoot on location, to follow subjects through their everyday lives, leading to groundbreaking documentaries--and to marathon sessions of MTV's Real World.

Keeping 'Hope' Afloat

IN THE SUNNYVALE studio that he shares with a laser exhibition company, Anderson roots through a pile of black tapes that are half the size of cigarette packs. They fill a shoe box next to one of his giant monitors. A handful of tapes are scattered in a trail from the shoe box to the camera that he uses like a VCR to play tapes and dump footage onto the computer.

His voice is raw and clipped as he discards tape after tape searching for the right one. He glances at his watch often. Despite all his hard work, Anderson has fallen way behind schedule. Hope debuts in just a few weeks, and he is still editing footage--and not for the first time.

But Anderson's problems go beyond editing. Though he's had one film to practice on, Partners for Life, which he shot on 16mm film, Hope was as much of a nightmare to put together as any underfunded independent project.

What went wrong? Well, sort of everything. "It's all ugly," he confesses.

"It's not Hollywood smooth. The cast and crew are not getting paid," Anderson says. "We shot for 20 days. It's hard to keep people into the project without pissing them off. There are personality conflicts. You can't just yell and scream. You do what you can to keep people happy. It's a constant struggle."

After spending months writing the script and auditioning actors, Anderson put together a shooting schedule that finally accommodated everyone's paying commitments. Then it fell apart. One of the leading actors quit; her mother was offended by the script. Anderson found a new actress and spent months working around other people's calendars to shoot what could have been done in a few weeks.

Then, a box full of tapes in hand, he locked himself in the editing room. For months, he did nothing but decipher unfamiliar software and narrow down his 20 hours of footage. Finally, he could begin weaving a story together.

Although digital video does not eat up vast amounts of computer memory, it still represents a lot of information: thousands of color images and sound. Few consumer computers can hold more than two dozen minutes of footage, so Anderson could never save a complete copy of his film. Instead, he edited Hope in 20-minute sections. When each segment was done, he would record it on a tape, erase it from his computer, then do another 20 minutes.

Anderson finds the tape he's looking for, puts it in the camera and records it on his computer. Four boxes appear in a window on his monitor. He clicks on one and a scene plays. A wide-eyed girl with duct tape over her mouth squirms on the couch. Another click and a guy on the same couch talks while rubbing his hands together nervously. Another click and a second girl enters the room, swinging the door open. Anderson links the scenes, connecting them in just the right spot, then moves on.

Since he can't store the whole movie on his computer, the tapes are the only complete record of the film he has. And that's why Anderson is getting so good at editing. Each of his previous two versions of the film had problems. Unable to just download another copy onto tape, he had to go back to the editing room to start again.

"It sucks, but I'm not going to spend the $20,000 it takes to get heaps of memory," he says, fishing in the box for another tape.

Cash may be at a premium, but time is the one commodity that independent filmmakers have in abundance. That, says Brian Boyl, a visiting professor at the UCLA School of Film and Television, makes digital systems a perfect tool for independents. Even the kind of 3-D animation in Antz or Toy Story is possible, given time.

Boyl himself couldn't resist the lure of having his own studio at home and recently went out and bought some digital equipment. Once a month, he shoots short films with his friends and edits them at home. That kind of accessibility, he hopes, is going to improve the quality of filmmaking.

"If you're in art school, you do a bunch of drawings to hone your skills," he says. "If you write, you write a lot. It's absurd that in film, if you're lucky, you get a chance to make something every three years."

By allowing filmmakers to practice more, he hopes that inexpensive digital technology will put a few cracks in Hollywood's wall of nepotism, opening the door to more good stories.

"With film, the costs are front-loaded," Boyl says. "You come up with a bunch of cash upfront, then shoot the film. With digital video, it's the opposite."

Independent filmmakers can shoot a film on digital video and show it to a production company before getting funding. It puts more emphasis on creating quality stories, Boyl believes. And having a tape in hand just may free companies to take more risks on no-name quality projects, and maybe even give them the fortitude to turn down horrible big-name movies.

Anderson agrees. He understands that Hope will not win him fame and fortune. It's more of a demo tape, something to convince others that he can write, direct and produce: "If you want this movie, buy it; if you want, I'll reshoot it in film. If you want a different one, I'll write you another one."

Projecting the Future

IN A FEW YEARS, Anderson and others think there will be a huge opportunity for digital video to become the medium of choice not just for making but for showing movies--and again, it's because of money.

Right now, every theater that shows a movie must get a 35mm print of the film, costing between $3,000 and $5,000. For a blockbuster opening in thousands of theaters, costs easily reach into the millions. When the movie closes, the print has been shown so often that it is totally degraded and useless. "That's just money down the drain," Boyl says.

Digital projectors are just starting to reach the quality needed for theatrical showings. Soon movies will no longer need to be output on film but can show up in any number of forms. With more films to come on digital, backers are hoping the technology will take off.

This fall Cyberstar, a Mountain View company, completed the first satellite distribution to theaters of a documentary called The Last Broadcast. The film was uplinked to a satellite, and then a few small theaters downlinked it and played it on digital projectors. It was a success that circumvented all the common distribution companies, instead keeping the arrangement between filmmaker and theater.

Anderson hopes that satellite distribution will open up the market for independent films. Since digital films are so cheap to make, they could recoup their costs in a few weeks, he says, envisioning a new regional film market.

Boyl is a bit more cynical. "I always think the people with the big bucks will run the show," he says. "Major distributors are going to have large teams of people thinking about how to maintain their cash cow." Satellite distribution will probably come down to a battle between film distributors and telecommunications companies, leaving independent filmmakers as out of the picture as they are now, he figures.

The real future for independent film is on the web, according to Bart Cheever, director of D.FILM, a traveling digital film festival that will be part of Cinequest. Already, Cheever offers films on his website and is encouraging people to make small web-based films that require little bandwidth and memory. As bandwidth and compression technology improve, more independent movies will move straight from the maker to the viewer, Boyl and Cheever say. Films of all kinds will one day multiply on the web like porn sites.

Anderson stops in mid-edit to pick up the phone and return a page, this one from a friend who is putting together the promotional poster for Hope--for free. He's trying to help her get a free scan; everything else, the printing, the paper, even the design, has been donated.

"Tell him he can put his name on the poster wherever he wants, a little promotion might help," Anderson offers, trying to finagle another in a year of favors that have kept his budget so low. Looking up at the footage on the monitor, he drags in a new scene, pushing a little closer to the end of his movie.

Digital Cinematography, a workshop with Pierre de Lespinois of Talisman CrestFilm, Laurence Thorpe of Sony, Steve Kotton of PVR and wildlife photographer Feodor Pitcairn, takes place Feb. 27, 6-7:30pm.

Editing (Digital vs. Analog) takes place Feb. 28 at 10:30pm.

D.FILM, a showcase of digital films, takes place March 2, 7:30-9:15pm.

All events are held at the UA Pavilion Theatres in downtown San Jose.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Point and Shoot: A scene from director Pete Anderson's 'Hope,' which screens at Cinequest.

Hope screens Feb. 26 at 11:15pm.

From the February 18-24, 1999 issue of Metro.