![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Eggstra, Eggstra

What happens to all the unused embryos frozen by fertility clinics year after year? Medical researchers, pharmaceutical corporations and even adoption agencies each have their own answer.

How the unborn have become a new kind of property.

By Dara Colwell

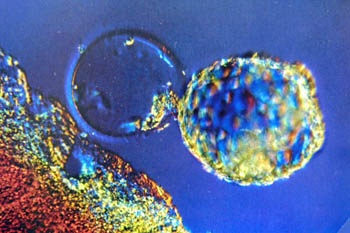

LIKE MOST PROUD PARENTS, Donna and Tim Zane put pictures of their newborns--in this case, a healthy set of triplets--in a baby photo album. Inside there are bird's-eye shots of the infants snapped days after birth, and a grainy ultrasound inside Donna's uterus. There is also something a little more unusual in the collection: a black and white photograph of four viable embryos, each a bubbly yet faint collection of cleaved cells, nestled within the zona pellucida, or outer shell. This is the first picture in the album--the "Very Beginning," as the couple likes to muse. Donna Zane carried it in her purse for months.

After four years spent waltzing between fertility clinics considering their options, the Zanes got lucky--Donna got pregnant on their first attempt with in vitro fertilization. If the initial procedure had been unsuccessful, the Zanes' six remaining embryos, which had been frozen and stored for future use, would be used for a second round. Luckily, three embryos from the first round successfully transferred into Donna's womb. Today, those delicate orbs of early cells are toddlers Amanda, Parker and Timothy, or TJ, three tots who have hit what their daddy calls the "terrible sixes." "It's the terrible twos times three," Zane explains, talking over TJ, who shrieks excitedly from his playroom. "Right now, it's 'No!' to everything."

A year after the children were born, the couple began considering what to do with their surplus embryos. "We knew they were there. We knew we weren't going to try for any other children," Donna, a former accountant, says. "Before, we were so focused on the procedure and finding out we were pregnant, we really didn't think about the ones that were frozen." But after discussing their embryos' possible fate--they could be donated to science, to another couple or discarded--the Zanes decided to opt for adopting them out. "After seeing that first picture and having the children, we knew we couldn't destroy them," she says, referring to the embryos. "We're pro-choice, but we didn't have strong feelings before the children were born. That picture did it for us--I look at it now and wonder which child was which."

The Zanes faced a dilemma affecting an increasing number of couples who have turned to modern fertility procedures to conceive a child. Since 1978, when the world's first so-called test tube baby, Louise Brown, was born, more than 20,000 similarly conceived babies have been born throughout the world. Originally viewed with distrust, in vitro fertilization--where a sperm and egg are united in a petri dish and then implanted in the mother's womb--has become increasingly commonplace among couples whose fertility has been decreased by age, stress and other health factors. To increase the odds of fertilization, clinicians try to create several embryos at once. But along with the success of this reproductive technology has come unforeseen consequences: what to do with the leftover embryos.

These tiny clumps of human cells in the first stage of life--most of them frozen for potential future use--are becoming an exceptional type of property. Today there are hundreds of thousands of frozen embryos in storage in the United States. But unlike most goods that are donated or discarded according to the owner's desire, this new property has incredible scientific implications--and raises thorny ethical questions.

"It's a personal choice, but when you've got to pay the rent [on embryos in storage], you're going to have to make that choice," Zane says. "We didn't want to just wash our hands of the matter or sit on them for years."

The scientific community and private corporations have a deep interest in the fate of the nation's frozen embryos. Not only are they a source of stem cells, which can cure a myriad of diseases, but private corporations are also legally securing rights to manufacture through cloning those very first stages of life. And others like the Zanes seek homes for their pre-born by adopting them out to couples. Meanwhile the government has muscled into the debate over the embryo's moral status and its scientific use.

Petri Dish Politics: The battle continues over whether public or private enterprise will have the final say over embryonic research.

Soft Cell

AS A BLOOD VESSEL burst in her head, sending blood rushing into Beverly Chew's brain, the retired business lawyer suddenly fell over onto the sofa where she had just been watching television. Chew experienced a hemorrhagic stroke and her neurologist presented her husband with the very bad odds: only 10 percent of patients typically survive this type of stroke; his wife would either live or die in the next 48 hours. Chew lived, but her left side has remained paralyzed. A brace prevents her left ankle from flipping over and after two and a half years of extensive therapy, she can only walk a few steps from her wheelchair.

Bob Chew, a retired developer, says simply of his wife, "This is about as good as it's going to get." Chew, a self-effacing and dedicated husband, says there is nothing unusual about his wife's stroke--nor his desire to get hold of stem cells, which one day could potentially revitalize her brain. "The quality of life is so horrible with stroke, it's not worth living just waiting for the end to come. I'm a novice at this point, but we all have to do our homework," he says from his home in Alameda. "When you look at the choices, I believe stem cells are the answer."

Embryonic stem cells, which are derived from the inner cell mass of early human embryos, are "master cells" that can become any one of the 210 different types of cells in the human body, such as heart tissue, blood, neurons, cartilage or bone. Stem cells are culled from donated embryos--an excess from fertility clinics that would otherwise be destroyed--and are usually only days old, containing exclusively undifferentiated cells.

Proponents of the research suggest that these stem cells, once stimulated to develop into specialized cells and tissues--rather like being given a specific job description--could potentially offer treatment for Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, spinal cord injury and arthritis. They could also be used to treat stroke, which strikes 500,000 Americans each year, diabetes, degenerative heart disease and damage from burns. Preliminary research in mice has shown that embryonic stem cells, "triggered" to become heart muscle cells and then transplanted into the heart, have worked together with the organ's host cells, helping it to function. There is almost no realm of medicine, they say, that might remain untouched by their use.

"The potential [of stem cell use] for human beings is enormous," says Dr. Paul Berg, professor of cancer research and biochemistry at Stanford University School of Medicine. Berg, a Nobel laureate and member of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, believes scientists must pursue this breakthrough technology. "We owe it to those in need to explore all possible avenues that could lead to a cure."

While many advances have been founded on embryonic cell research, there are those who morally object to using this tissue. Groups like the Coalition of Americans for Research Ethics, a national group of medical professionals who believe that destroying an embryo is the same as destroyng a human life, say it poses an ethical quandary framed along lines of the decades-old abortion debate. "If you take the position a human life begins at conception, then naturally you gravitate to the position that you shouldn't destroy embryos either. This is a form of human life worthy of respect," says Gene Tarne, spokesperson for the Coalition. The Coalition believes the use of embryos could be avoided by using alternative sources such as adult stem cells, which are thought to exist in every tissue of the body. So far, about 20 different kinds of mature stem cells have been discovered, harvested from cadavers, blood and even fat cells.

"We believe it's unnecessary [to use embryos], given the advances being made with mature adult stem cells," Tarne says. "We feel the profession of science is to heal first by doing no harm. This will taint the medical profession by redefining the embryo as less than human--that it's just up for grabs for research purposes. It's a utilitarian way of treating life."

Tim Zane, however, doesn't oppose this kind of research. It's just not what he wanted to do with his embryos.

"The advances made through science are unbelievable," he says. "What people do with their embryos is their decision. If they donate to science, that's fantastic. It's a personal choice."

Stem the Tide

GERON CORPORATION'S Menlo Park headquarters, housed in two squat, white buildings with slabs of hospital-green paint near the roof, lies flanked by several office buildings along sleepy Constitution Drive. The aroma of cinnamon buns drifts from a neighboring building, and in the distance sweep sloping hills populated by electric pylons. In 1998, the biotech firm gained scientific acclaim when it announced that two of its research teams had isolated human embryonic stem cells. The company subsequently succeeded in cloning these cells, and in March of this year, Geron received U.S. patent No. 6,2000,806--a legal permit to manufacture human embryonic stem cells. In this way, Geron avoids the sticky issue of having to get ahold of new embryos to make products. They can simply manufacture their own.

Due to a congressional ban that had pushed embryonic stem cell research into the private sector (see sidebar), Geron spearheaded the science, tinkering with cells largely in private. Its efforts paid off and the biotech company has since licensed its cells for commercial use. Those cells are in high demand from the academic scientific community because previous federal guidelines banning research involving their use were recently altered. Now the government will pay for research using stem cells, but only after they have been collected. This means academic researchers still can't make them but they can buy them. Their source: primarily Geron.

This could turn a good profit for the company. Last August, the day after the federal ban was lifted, Geron's stock rose 63 1/16 points. Almost all biotech companies, even those with no association to stem cells, experienced an increase in stock price.

Due to the ongoing debate over embryonic stem cell research, Geron would not speak to Metro and referred this reporter to its website instead. However, Troy Newman, director of Operation Rescue West, a Southern California-based antiabortion organization that has targeted Geron, was eager to speak.

Two years ago Operation Rescue West, which routinely conducts "Show the Truth Tours," where volunteers cart 6-foot-tall placards displaying aborted fetuses, staged a three-hour protest outside the biotech company's doors. The protesters peacefully waved signs bearing pictures of aborted fetuses, but their only contact was with a security guard. "How can you patent a human being? It's absolutely bizarre," Newman says, his voice rising quickly over the phone. "Geron has patented a product to be bought and sold--are they going to start growing human beings like crops in the field? I'm a capitalist to the bone, but there's something wrong with this picture."

Newman, like the organization he runs, doesn't shirk voicing strong, even extreme views. The group's website, which features pictures of plastic vats containing aborted fetuses, declares to abortion seekers, "If the gates of Hell were a storefront on Main Street, wouldn't you tell the people going in about Jesus?"

"Life begins at conception--what's the difference between killing in utero or killing in a petri dish?" Newman says, claiming his outrage stems directly from that basic point of view. "It's an individual full of potential, dissected to improve the life of Joe Smith. What's worse, it's being done in order for huge, greedy corporations to make millions of dollars for themselves and their shareholders."

While other antiabortionists may prefer to play up what they see as a shocking destruction of human life, Newman's point about access to the pharmaceutical end-products is valid.

Private industry has led the science so far, and its efforts have been independent of both federal restrictions and public scrutiny. What's more, as long as the government leaves the work of obtaining stem cells to the private sector, biotech companies will likely have a monopoly on new therapeutic techniques. Their particular "product" could help millions, but only those with the money or insurance resources to afford them.

"We're drawing a fuzzy line in the sand that continues to be moved back at the request of corporations like Geron," Newman says. "Science has been proficient in curing all sorts of ailments, but it has to be done ethically. It starts with the valuation of human life. If human beings are a commodity, what are we going to evolve into?"

Frozen Snowflakes

'THE WEATHER REPORT: It's almost a blizzard!" reads a section on the Christian Adoption and Family Services website. "On December 31st, our first Snowflake--'Grace'--turned two!!!!" The Snowflake referred to is the Southern California-based adoption agency's first embryo to be placed with a family and born to an adoptive mother. Since then, seven babies--once frozen embryos, left over at fertility clinics--have been born; the most recent, "Joshua," arrived last December just outside San Francisco.

"No child is in excess; these are not unwanted children," says JoAnn Davidson, director of the Snowflakes program. "This is just like traditional adoption--the first position we take is that children need homes. That's our mission."

The Snowflakes project, according to Davidson, got started when a mother undergoing fertility treatment approached the adoption agency's executive director, concerned about who, exactly, to donate her eggs to. The mother didn't want her eggs destroyed, nor did she have a particular donor in mind. The adoption agency stepped in, establishing a program that has since matched 50 adopting families with 47 donors, including the Zanes.

"We always thought we would like to see another family raise the children," says Donna Zane who, with her husband, donated six surplus embryos to a California couple they found through Snowflakes. After the embryos were thawed, three survived and the adopting mother gave birth to twin boys six months ago. "It's just bizarre. You put dry ice on a plane, ship it to California and the result is two kids," Tim Zane says. "The whole process is just weird and amazing."

The agency, whose voicemail system informs callers in a mock baby voice to leave a message, acts as a liaison between families by helping facilitate a match where donor parents ultimately vet recipients. The Zanes decided on their first match after poring over the family's biography and several photographs of the potential parents. "We could see they had strong faith in their religion, good family values and they were financially secure," Zane says. The couples exchanged emails throughout the adopting mother's pregnancy, and when the boys were born "the excitement in their letters is hard to explain," Zane says slowly, remembering. "We gave someone the opportunity to reach a goal in their lives."

The entire adoption process actually works more like an exchange, or a legal transfer of property, than anything else. Snowflakes does not contract out to fertility clinics and neither the donor couple nor the fertility clinic receive any money from the transfer. The only payment is the adoption fee, roughly $4,000, which covers home study, a traditional screening process in adoption services. Out-of-pocket medical expenses, such as shipping embryos from one clinic to the next, are covered by the adopting parents. Currently there are no states with laws governing embryo adoption. Under California law, the transfer of embryos falls under the common law Statute of Frauds, or Penal Code Section 367 (b), a mere paragraph which requires written consent between parties.

"These embryos are fragile, frozen, unique and created by God," says Davidson, whose job is a passion. "We're against their destruction, whether they are one cell or 1,000. There are 2 million infertile couples in America and the need is there."

Fertile Dreams

EMBRYOS, HOWEVER, do not come with a motherhood guarantee. During the freezing and subsequent thawing process, between 25 to 50 percent of embryos are lost, and even with fresh embryos, live birth rates hover around 33 percent, according to Dr. Richard Schmidt, an infertility specialist at Nova IVF fertility clinic in Palo Alto. Schmidt explains that while a high percentage of embryos may be successfully fertilized, a smaller percentage successfully implant, resulting in actual pregnancies. That percentage is further reduced in terms of live births. This process naturally occurs within the body, which selects only the strongest embryos to survive.

Still, the demand could easily be supplied. While no official numbers exist, there are an estimated 150,000 embryos stored in liquid nitrogen nationwide. According to one report, there could be as many as 25,000 in Maryland alone, due to the state's favorable health insurance coverage for fertility procedures. In countries like Britain, excess embryos are destroyed after five years, but in America there is currently no time limit on storage. According to Christian Adoption and Family Services, there are 1,050 parents of frozen embryos who are aware of their program. But Snowflakes has worked with only 253 parents so far, which represents less than half of one percent of all the embryos in storage.

"It's a moral dilemma and [fertility] doctors are afraid to broach the subject because they may be afraid they're walking an unethical line," says Theresa Erickson, a San Diego attorney who specializes in assisted reproduction issues. Erickson, who began working with embryo surrogacy transfers in 1993, says it has been a slow process getting the word out. She currently works with about 10 couples a month interested in donating their embryos. "It is indeed property, but I can't just advertise it in the newspaper. There's the concern that this is not only tissue but something with a soul," she says. "I have to wait for parents to contact me."

"We never got into a discussion with our clinic--they removed themselves from it," Donna Zane says about donating her embryos. The Zanes were the clinic's first couple to find a new home for their frozen embryos. "It was really up to us to figure out how to do this."

Life and Death

ONE WEEK INTO HIS PRESIDENCY, President Bush said that federal money should not be used for research on fetal tissue or stem cells derived from abortions. "I do not support research from aborted fetuses," Bush said, repeating sentiments he expressed during his campaign. While Bush did not specifically address embryonic stem cells, researchers have since feared that the federally lifted ban, implemented by former President Clinton last August, might be reversed.

The battle ahead appears politically thorny because embryonic stem cell research is not only inextricably linked to the abortion debate, it also pits anti-abortion activists against ailing patients and the elderly, who are the most likely to suffer from Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. And the debate is fractured because whatever the embryo's exact moral status, using embryonic cells for potentially life-saving research seems preferable to simply discarding them. The old alliances of the abortion debate, therefore, are no longer so clear-cut.

As it stands today, ethical issues persist. "It's political dynamite going into this area," says Serena Alvarez, a second-year law student at Stanford University. Alvarez, who is pro-choice but against embryonic stem cell research, is writing a thesis on the subject. "The Supreme Court won't touch it, Congress won't touch it, but it has to be dealt with. There's no clear legal basis for when an embryo is considered 'alive.'"

Alvarez points out that a legal definition of "life" could be formed using the precedent of the Uniform Determination of Death Act passed in 1980, which set legal guidelines for biological death, such as brain death. "How can we take part in this debate when (the embryo's) status is still undetermined?" she says, noting that medical advances have made it necessary to reevaluate. " The research doesn't make any sense unless we decide when life actually begins."

But that determination may arrive somewhat surreptitiously--and not without political strife. Just last week, the House approved legislation making it a crime to harm a fetus while assaulting a pregnant woman. If passed by the Senate, the "Unborn Victims of Violence Act" would effectively define the fetus as a separate person, on par with a living human being.

Wherever the debate takes us linguistically and legally, it is definitely bringing new questions to light. "We're moving into a biological revolution," says Dr. David Prentice, professor of life sciences at Indiana State University. Prentice is a member of the Coalition of Americans for Research Ethics. "There are going to be many more ethical debates along the way, depending on what paths we decide to take now."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the May 3-9, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.