![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Diet Grrrl

Christopher Gardner

After spending tens of thousands of dollars at Stanford's state-of-the-art eating-disorders facility, a Palo Alto teenager cures her anorexia with punk rock.

By Amy Paris

On a sunny spring afternoon, in the dimly lit dungeon from which Stanford University's KZSU broadcasts, 15-year-old Debra Rolfe cues up an old-style black vinyl LP. Carefully timing the segue for maximum effect, she unleashes 500 watts of angry punk-rock on the world.

Meanwhile, four or five friends crowd into the tiny on-air studio, making it somewhat of a feat to get past the mixing board to the microphone. The red on-air light flashes, and a brief moment of silence is interrupted by a round of teenage giggles.

"This week, we're looking for bratty songs, and songs about menstruation," Debra says. "If you have one, call in."

A small throng of streaky-haired teenagers loiters outside the studio, occasionally running to the music library to bring out some record or another. When it's time to talk on the air, they all crowd around the two microphones, rating music, magazines and other artifacts of teenage culture with a refreshing lack of pretension.

"Call in," Debra chides her audience. "There's gotta be more than one of you out there listening."

Welcome to "What Is Happening to My Body?," a high-concept radio show dedicated to exploring issues of interest to teenage girls, including feminism, anorexia and punk rock.

Debra, who recently completed her sophomore year at Palo Alto High, later gets to talking about the all-woman punk-rock band Bikini Kill, her voice amped with an infectious enthusiasm. She explains that the band turned her on to both feminism and music, which in turn helped her cure her anorexia.

After having landed in the hospital two years ago with the life-threatening eating disorder, Debra feels that Bikini Kill helped save her life. She says music finally gave her a voice to express her anger.

"The music was saying stuff I actually felt," she says. "Finally I found a culture, a style, I fit in with. The music was like 'Fuck you,' and I was like 'Fuck you.' That was how I felt, and still feel.

"Even in our supposedly liberated culture, I grew up with this repressed background, in that girls are not supposed to make trouble. I saw that boys would do stuff, while girls watched. I always thought that was lame.

"I realized that starving myself was totally buying into mainstream white male culture. Lame."

Body Trouble

Because she had always been a skinny kid, no one noticed when Debra began to shed a few pounds in eighth grade. Her Bat Mitzvah was approaching, and the family was busy with preparation. Debra spent long hours learning the Hebrew verses just right. She felt an intense, self-inflicted pressure--reinforced by family and religious leaders--to be perfect for her big day.

Meanwhile, her 13-year-old body was undergoing the physiological changes of adolescence, which included a belly that began to curve outward. At a time when peer acceptance mattered more than anything else, Debra saw her "fat" as an extraordinary liability.

"I truly thought I was getting pudgy," she says. "I remember looking at Seventeen, and the girls were so skinny. I thought I was not normal anymore."

She decided that she had to go on a diet. Her friends and family say Debra is good at everything she does, and dieting was no different. She started out by eating healthier foods.

She cut out snacks, then all sugar, then fat. She started eating less during meals. Soon, she found herself working out every day. Inevitably, she began to lose weight.

After about three months of dieting, Debra began to sense that something was out of control.

"I didn't understand what was happening," she says. "I didn't know what to do. I was afraid."

Debra told her parents she needed to go to the doctor. She recalls their reaction. "It was like 'Not my baby, not my child,' " she says.

By the time her doctor's appointment rolled around, her 5-foot, 7-inch frame weighed a scant 90 pounds.

She went straight from the doctor's office to the hospital. "I was pretty messed up at that point," she says.

Her dieting had taken on a life of its own, turning into full-blown anorexia.

"I didn't really admit it to myself until I was in the hospital," she says.

This was the last thing Debra's mother, Diane Rolfe, expected. She says Debra grew up in a family with a genetic tendency toward thinness and a healthy attitude toward food. But a speedy metabolism wasn't the only thing Debra inherited from her mother.

"We're both perfectionists," Diane says. "Debra is a very good student, as I was. She is very strong at everything--her work ethic puts me to shame."

In retrospect, Diane Rolfe says she feels that it was her daughter's perfectionism, catalyzed by intense preparation for her Bat Mitzvah, that led to the eating disorder.

"The Bat Mitzvah was the straw that broke the camel's back, I realize now. Debra really internalized the drive to be perfect. The cantor, who does the musical element of the service, was really hard on her. I was not aware of that. I almost got sick when I found out."

Hunger Artists

At 13, Debra was exactly the average age of anorexic patients at Stanford's Packard Children's Hospital, according to Tom McPherson, a medical specialist in adolescent eating disorders. McPherson estimates that 8 percent of high schoolage girls are struggling with a full-blown eating disorder, while many more have subclinical cases.

"We did a study where we found that about 60 percent of girls say they have dieted by junior high," he says. By the time they reach high school, according to a poll of 500 students conducted by Palo Alto High School's newspaper, 77 percent of females (compared with 30 percent of males) have dieted.

The same poll found that one in four girls had starved herself in the past year, and 15 percent considered themselves anorexic.

As any dieter knows, it takes willpower to withhold food from a hungry body. This willpower is energy that might otherwise be spent studying, playing sports or on other productive activities. Dieters become preoccupied with food, resulting in restlessness, loss of concentration and, sometimes, obsessive behavior.

Eating disorders almost always begin as diets, McPherson says. In a culture which holds extreme thinness as its ideal, rising numbers of young women are being counted as casualties.

Diane Rolfe, who teaches social studies at Jordan Middle School in Palo Alto, says teenagers today face a much more hostile environment than the one she knew growing up in the suburbs of Portland, Ore.

"I'm 53 years old, so I grew up in a completely different culture. Anorexia was completely unheard of then." Recently at Jordan, one of Diane's students passed out in the hallway from self-inflicted hunger.

"Not eating correctly is epidemic among our young people," she says, laying the blame on fat-free fads and vegetarian bandwagons, as well as the stressful Silicon Valley lifestyle.

The dieting ethic is also perpetuated by many doctors who, despite the evidence that most diets fail and that dieters tend to gain back more weight than they lose, continue to prescribe ineffective treatments and sometimes dangerous drugs to people who are only mildly overweight.

Girls are particularly susceptible to eating disorders during adolescence, a time when they are maturing physically and sexually. Dieting, some researchers say, serves the dual function of putting off the physical transition to womanhood and restoring to girls some control over their changing bodies.

Crunching Calories

A hospital stay for anorexia treatment, the Stanford Clinic has estimated, will cost patients an average of $150,000. Considering that many will require a second and third hospital stay, along with months of nutritional counseling and therapy, the cost is often much higher.

Extreme costs and decreased support from HMOs and managed care providers have closed down many of California's eating-disorders clinics in the past year.

The Stanford clinic, the only one of its kind in Northern California to remain open, has seen a 50 percent increase in patients in the past year, up to about 75 new patients from 50 the year before.

"We are swamped," McPherson says.

When he talks about the cost and availability of treatment, McPherson's voice takes on an edginess.

"If anorexia was a problem that men got, do you think insurance companies would exclude it from treatment?" he asks angrily.

After Debra spent 25 days in the hospital, the Rolfes' insurance coverage ran out.

Joe attempted to have his daughter released, but he was told that it would be against medical advice to do so. For the remaining week of Debra's hospitalization the bills began to pile up.

It took more than a year and a near-lawsuit to get the insurance company to settle the $20,000 hospital bill, incurred from five days of uninsured treatment.

Model Patient

In retrospect, Joe questions the judgment of the doctors involved. He chooses his words carefully.

"I have often wondered if the family doctor, who is a longtime friend of mine, didn't overreact in the first place," he says.

Debra insists that the shock of being hospitalized was the jolt she needed to realize the severity of her self-destructive behavior. She calls her stay on the anorexic ward at Stanford hospital "a hideous experience," where everything revolved around numbers: Her blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and the number of calories she had consumed seemed to matter more than how she was doing psychologically.

Debra hated the anorexia "scene" at the hospital. "Anorexia becomes your life," she says. The girls would plan their days around food, making it difficult to unlearn poor eating habits.

"The less time you spend in the hospital, the easier it is to get over," she now says.

McPherson admits that there is controversy in the medical community as to the best form of treatment. He is somewhat ambivalent about the Stanford Hospital program's strict reliance on calorie-counting and weigh-ins, acknowledging that the technique gives the anorexics, who are already obsessive about food, something else to obsess over.

But he finally comes down in favor of the program.

"They're going to obsess anyway, and the positive outweighs the negative," he says.

Debra eventually got out of the hospital not because she was cured, but because she learned how to work the system.

"I knew the weight where I couldn't get in trouble, and I kept it there," she says. After she got out of the hospital, though her weight was no longer considered dangerous, Debra says she was still stuck in an anorexic way of thinking.

"I couldn't eat without problems," she says. "It still controlled my life."

Debra's condition did not improve until she saw another doctor who gave up the number-crunching. Gradually, she learned to listen to her body and to eat when she was hungry.

But Debra says her true cure finally came when she found a place where she fit in. The place was KZSU, where she enrolled in a DJ training class last winter.

At the station, she met people who treated her like a unique individual instead of a social outcast.

"Working at KZSU, it disappeared," Debra says. "I didn't have time to be anorexic."

After three months of DJ training, Debra got her first radio show last spring. Each week, her mom and dad would drive her to the radio station at 3am.

"It was really supportive of them," she says. By the summer, "The What's Happening to My Body?" show had earned itself a drive-time slot, from 3 to 6pm on Tuesdays, where it has remained for four academic quarters.

In addition to her radio show, Debra has been busy with other projects. She plays bass and drums in two bands. Along with some friends, she has created a zine (which she defines as "an underground D.I.Y. publication often made by lonely suburban teenagers in order to get in touch with other people like them") called King Bacon Press.

She is also working on a personal zine, the first issue of which will be all about eating disorders. "Anorexia is so much a part of who I am. It forced me to examine a self-destructive impulse in me," Debra says.

Her experience with anorexia turned Debra into a social activist. Instead of being shamed into keeping her disease a secret, she is trying to raise awareness and draw attention to the epidemic of eating disorders.

Highest on her list of concerns, however, is that many kids are still experiencing the same isolation which she felt not long ago and which contributed to her anorexia.

To combat this isolation, she has helped found an organization called Suburban Underground Conspiracy Kids, or S.U.C.K.

"Through other projects, I have met lots of kids who are doing the same stuff but have never met each other," she says.

The mission statement of the S.U.C.K. organization best explains the viewpoint of its members:

S.U.C.K. is our organization, cuz we feel excluded and silenced by other existing groups. ... S.U.C.K. is not about cliques or exclusion. We are just a group of suburban kids who are sick of the pattern. Apathy under the guise of rebellion is sold to so many of us, but we wanna resist it. We want change now! Our starting point is organization.

Off to a promising start, S.U.C.K. now boasts more than 30 members. They have organized two benefit concerts and a yard sale and are currently looking for a Peninsula-area building in which to put on all-ages rock shows.

Debra's parents admire their daughter's adventurousness and energy. Although they would rather Debra named the organization something other than S.U.C.K., they support her goals.

"I'm starting to realize to what degree she feels alienated by her peers," Joe said. "I am very pleased that she's taken the initiative to, shall I say, fight back."

The Rolfes are somewhat unique, in that they've been able to look beyond their family, into society, for the source of their daughter's eating disorder.

"Often, families have a hard time being advocates because they buy the idea that it's their fault," says McPherson, the counselor at the Stanford eating-disorders clinic.

At a still-lanky 115 pounds, Debra considers herself mostly cured. But like alcoholics, anorexics have to maintain their resolve in the same settings that sparked their disease in the first place.

Debra admits, "I still have days where I don't like my body."

When she begins to feel this way, "I do something else--get busy.

"That way I don't have time to worry about it."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

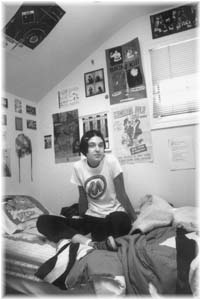

Teen Spirited: Debra Rolfe, who found relief from her eating disorder by DJing a punk radio show, says the band Bikini Kill may have saved her life.

From the June 26-July 2, 1997 issue of Metro.