![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

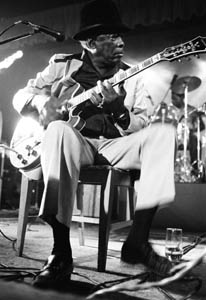

Photograph by Dave Lepori

Delta King

John Lee Hooker, who died last week, catalyzed the transatlantic blues rock revolution as well as a vibrant blues community here in the valley. The legendary musician shared his thoughts in this 1987 Metro interview.

By Sammy Cohen and Dan Pulcrano

John Lee Hooker died Thursday, June 21, 10 days before he was scheduled to perform at Saratoga's Mountain Winery. Ads promoting his appearance even appeared in the Sunday newspapers after his death. Talk about playing it right up to the end!

John Lee will be buried after a Thursday service at Oakland's Mormon Temple. Information can be found at the www.rosebudus.com/hooker/ website.

I had the good fortune to catch his show at the Icon just a few short weeks ago and was impressed to see that John Lee still had some of the magic that hit me like a thunderbolt the first time I saw him perform. Not long thereafter, Metro music writer Sammy Cohen and I interviewed him at his Redwood Shores home.

We're pleased to reprint that 1987 interview below, along with remembrances by arts critic Gina Arnold and photographs from that landmark period of his career by longtime contributors Franklin Avery (cover) and Dave Lepori (inside shots). --Dan Pulcrano

BOOM-BOOM-BOOM-BOOM. The man with the hat in the straight-back chair is midway through his set, and outside the small club on Stevens Creek, an overflow crowd dances in the parking lot. A TV cameraman strains for the best possible angle in the wall-to-wall club to support a thesis that blues is hot currency in the South Bay. "We're a little late on the story," the reporter admits.

A-how-how-how-how. The septuagenarian is recognizable from the portrait that hangs to the left of the stage. Tonight the legend comes to life, after knocking back long-necked beers by the pool table and autographing albums with a fat black marker. Anything but reclusive, the outgoing John Lee Hooker has been gathering zero moss, touring four weeks out of the year, including recent appearances at JJ's, Paul Masson, SJSU's Fountain Blues Festival and a set with Bob Dylan onstage at Shoreline.

For Hooker, music is anything but a business. The blues for him is a mission and a message. And although he influenced Clapton, Dylan, Hendrix, the Stones and ZZ Top--as well as newer stars like Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan--he's now touching a whole new generation of musicians, perhaps best exemplified by the recently signed local blues harp phenomenon, 17-year-old Little John Chrisley.

A week after his January 30 appearance at JJ's, Hooker sits on the edge of a bed in his Redwood City home, flipping TV channels by remote control and talking about why blues musicians are leaving Chicago and Detroit for the South Bay and East Bay. As the acknowledged spiritual leader of Northern California's blues community, Hooker takes his responsibilities seriously.

When the thought crosses his mind, he combs through one of two address books he keeps on the nightstand, picks up his Kermit the Frog phone and dials a number. "This is Mistah Hooker," he says, and tells the parent of a musician he fears is going astray that he knows of some work.

His mere presence on the scene is an inspiration to local blues musicians. "It was about '74 when I saw Hook's band with guitarist Luther Tucker," says local blues harpist Gary Smith. "The reality of having Tuck and John Lee living here transformed the scene. When Charlie Musselwhite, Paul Butterfield and Nick Gravenites moved out here, they gave the Bay Area a boost. But John Lee was a bonafide anchor for local blues musicians--a godfather. We were all locals, playing good and trying to make things happen, when Hooker's arrival made things official."

Guitarist Ron Thompson says, "I got hired by him in '75. It was fun times touring Canada and the States with Hook. He invented the style he does. How often do you get to play with someone who invented a musical style? "

With blues musicians like Robert Cray making radio playlists and magazine covers, Hooker sees the musical form he helped pioneer finally taking hold. "Yes it is, just like a bright, bright sunny day," he says with obvious delight.

"I'm going to explain it, and I hope you understand. More younger people are into the blues now. More people are trying to play the blues. The blues tells a story. Every line of the blues has a meaning. The stuff they call rock & roll and punk is taken from the blues," he says.

"It's saying the same identical thing that we are sayin'--about women, men, whiskey and money. Every song you hear, I don't care if it's a ballad or R&R--it has got something to say about women. So that's what we sayin' in the blues. They got that from us; they just dressed it up.

"The kids are out there have a good ol' time, and that's all over the world. You can go to Europe, and there's no turnin' back--any parts of Europe. Wherever you are, there is no stop and go for the blues. The blues go but it don't stop."

HOOKER WAS BORN to Mississippi sharecroppers about 50 years after the Civil War. His long road from the Clarksdale cotton fields to Carnegie Hall saw the world change dramatically during the 70 years he has been on the planet, with two World Wars and an explosion of science and technology like civilization has never seen before.

Heir to a tradition that also spawned Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson, Hooker fell in love with the dark and powerful sounds of the Delta blues. The toil and ignominy of Southern life was something else again, however, so Hooker hit the road at an early age.

"I left home headed for anywhere," he says, "I was 14 ... carryin' a guitar and a few li'l rags o' clothes. My destination was 'away from Mississippi!' Get away from the cornfields and the cotton fields.

"I hitchhiked, took trucks 'n' trains--anything that would pick me up. I stopped in Memphis for about six months and they found me and come got me. Stayed about a month an' split again. [Chuckles] I didn't stop in Memphis that time. I went on to Cincinnati. I had got a taste of the big cities and them bright lights. I stayed there until I was about 18 or 19 and then I went on to Detroit.

"The Cincinnati music scene was all right. It was so-so. I was jus' on my own there. I was workin' in theaters and the places I could work. I was playin' by myself. I didn't play nightclubs because I wasn't old enough. I jus' played house parties.

"This lady I was livin' with, called Mom, she had this big house. Had a li'l job and worked throughout the week. Weekends, I played for her. She give parties with servin' liquor 'n' stuff like that. And we stayed up all night ... after hours.

"She give me a few dollars. That was big money back then. But playin' music, I really got into it big when I hit Detroit. A lot o' work was goin' on ... wartime, World War II and the factories were goin' and every city was boomin'. Detroit was boomin'."

WHILE IT HAS BEEN SAID that Hooker never needed much more than an E string on his guitar and his deep-throated growl to get his music across, Hooker was truly a pioneer of the urban rhythm and blues that evolved in the mid-'40s. Hundreds of thousands of jobs in the auto steel industry encouraged Southern blacks to come north. This was their music.

In the Windy City, Muddy Waters was advancing the cause of the industrial strength Chicago blues with the amplified guitar, harmonica, bass and drums. In 1948 Hooker's star ascended with his hit recording "Boogie Chillun'," a solo effort on Modern Records that synthesized the Mississippi Delta and urban blues with brooding intensity.

In his early childhood, Hooker was introduced to music by his stepfather, Delta bluesman Will Moore. "He played guitar, too. He had a Stella. That's what I learned on. I checked out electrified [guitar] in the '50s but it wasn't 'til 'Boom Boom' [1962]--that's when I really stretched out on the electric," Hooker says.

"T-Bone Walker--he give me my first electric guitar. I was already established but not electrified. I still have that old Epiphone that T-Bone laid on me back in Detroit about 40 years ago."

In the years that followed, Hooker wrote and recorded prolifically for labels like Vee-Jay, Cobra, Chess and Regal--often under such names as Texas Slim, John Lee Cooker and Johnny Lee.

"In my career, people in the record business have been rockin' in the same ol' boat. They all crooks--I'll say it clear and loud--especially the big ones. All but this one I'm with now. This new record I got out, 'Jealous,' on Pausa Records in L.A.--they be a small company but I really believe they're honest. But the rest of 'em you can put in one basket and you don't care which one fall out first--Chess, Vee-Jay, ABC ... Everybody tryin' to sue 'em now ...

"Since you knew they was goin' to cheat you anyway, I recorded under any name with all of 'em. They wasn't gonna give you nothin'. I didn't care as long as they let me play my music. Cash on the spot ... You cheat me and I'm gonna get me some money, too.

"But the music business has changed. Record companies got more respect for artists 'cause they know what they're doin' now. I know it's changin', and I'm so glad of that. Groups are corporations now. They have pension plans. Musicians have saw the daylight.

"A long time ago the artists didn't know about publishin', writin', and royalties. But now I got my own publishin' company. It's called Boogie One, like the license plate on my Mercedes. I know all that stuff now. Then, it was jus' cut the record and 'Here it is.' And then I'd be thinkin' they was gonna do me right, but they was gonna do me in."

The early '60s ushered in a blues renaissance in Europe. Hooker toured the continent in 1962 when English rock fans were discovering black urban blues. Some of the superstars that cut their musical teeth opening for his act were the Rolling Stones, the Animals, John Mayall and Eric Clapton. Hooker is not surprised by the large and devoted following that the blues has in Europe.

"It's pretty much easy to go figure out. They don't get as much music as we get; whatever they get, they really 'preciate it. They stay hungry for it all the time. But over here it's everywhere.

"The one thing the blues don't get is the backing and pushing of TV and radio like a lot of this garbage you hears. They choke stuff down people's throat so they got no choice but to listen to it. If they played more blues, people would just get it--they try to hold it back but just about can't hold it back now because the blues is really going.

"But it would go much further if it got that support on TV like rock & roll and punk rock. They take money, hundreds of millions of dollars, and just make 'em stars. It ain't real! It's made with money ... They make you an artist and put you on TV. I'm not puttin' 'em down, but my little girl can get up and do that."

THE RECENT blues revival in the States, especially in Northern California, is primarily a musical discovery by urban whites for urban whites. When asked if genuine blues--a music born out of poverty and pain--could thrive in the mild climate and relative affluence of Northern California, Hooker shook his finger and admonished, "Like I repeat to you, young man, you can have Rolls Royces', you can have a Mercedes ... I got a Mercedes sittin' out there; I got a red Toyota Supra out there and a 380 SL out there in the garage, but still that don't keep me from havin' the blues.

"I have heartaches, I have blues. No matter what you got, the blues is there. 'Cause that's all I know--the blues. And I can sing the blues so deep until you can have this room full of money and I can give you the blues.

"So, even if you're surrounded with the good things and the money, you can still have the blues. The president can have the blues. It jus' goes on and on.

"Like you and your woman ain't gettin' along and you're in love. You can't sleep at nights. Your mind is on her--on whatever. You know, that's the blues. You can't hug that money at night. You can't kiss it.

"A lot of young folks--they don't have to be black or poor--even rich kids, a lot of them are very unhappy. They run away from home, they get strung out on dope. They don't know what the blues are, but they got 'em, and they really don't know what they got. They got that sad, sad, feelin'. Feel like they ain't wanted.

"Some come from rich families. Some come from families that don't have money ... Kids are so strong nowadays. They want to get out there with what's happenin'. They think dope is the thing. They get so far gone they get wasted. They got no place to go but back home, but they ain't goin' back there. So they're turnin' to the blues. Some of 'em don't know what the blues are, but that's what it is ... heartaches, misery.

"It's sad to see beautiful people wasted on drugs. They get so far gone. They wanta turn back but they can't turn back. They can't support their habits and they sell the clothes off their back--even sell the clothes off your back, but still they don't mean to hurt you. But somethin' hurted them and they are tryin' to get the monkey off their back. Once they do that they're quiet for awhile. They may steal from you, then they're sad later. Some people really want to hurt them, but they are good people.

"I got to these meetings, these halfway houses, and talks to 'em. Intelligent they are, and very sensitive. But they at a stage where they can't help themselves. They're not bad people, not by a long shot. It really is sad 'cause they wish they could change things. I try to find time to play for those people, like benefits. You know?

"I was just old fashioned. When I was comin' up there never was such a thing as all this stuff ... this drugs. I had never seen none. I just seen heroin here about two years ago--I didn't even know what it looked like. I didn't even know what cocaine looked like. I never smoked pot. I never used no kind of drugs.

"I tried pot once but it didn't do nothin' for me. I used to drink, but I don't use hard liquor. Not any more. But I never did go overboard. I always could handle it in my music. I'd never get to the place where I couldn't play, couldn't stand up. I used to get pretty stoned, but I could always do my work."

Hooker moved to the West Coast in the early '70s. After eight years in Oakland, he moved to the Morgan Hill/ Gilroy area for about five years. These days Hooker resides in upwardly mobile Redwood Shores in a tract home close to the bay and the salt air.

He says he enjoys playing the smaller clubs. "I'd rather play them than play those big ol' sophisticated clubs ... people 'preciate it more. I can get out 'n' walk around and hang out with my audience--stand there and have a beer with them. I've played them all, a lot of big clubs, but I get more feeling out of the little ones.

"When I played Carnegie Hall--that's a big, big name--I didn't feel nothin'. It's like punchin' a time clock. They fined me $800 for going over one minute--they're strictly money and business over there in New York. It's prestige. But it's ridiculous.

"The little clubs, if you feel good, you just go for it. The people are jumpin' up and down. They screamin' and hollerin'. They boogieing. That makes you play better. But, if they're sitting there lookin' at you like a statue, you get pretty nervous. 'Hey,' you ask yourself, 'what am I doing wrong? Don't they feel? Ain't I doin' nothin'?' You get a big round of applause but when you go to playin', they're just sitting there looking at you.

"But in them funky clubs--some small, some packed with 2,000 people, folks all dressed in jeans ... places with old beat-up walls and bathrooms--it's funky, but it's good. It's real good."

Hooker has delighted in pushing the careers of young talent. He remembers when Bob Dylan was "just another person from the streets."

"I was the first person to put him on the bandstand--when I was playin' at Goody's Folk City in the Village back aroun' '65 or '66. He came there ... When I heard him I knew he had a lot of potential. My manager, Al Grossman, heard him and dragged him up and he never looked back. I always go see him when he's around. I'm glad to see him doin' so well again.

"There are a lot of great artists and blues people I've played with, but I would say that Stevie Wonder is somebody I'd like to work with. I know'd him from a little kid, 9 or 10 years old. I watched him grow up. He used to come on my street and play at a house of a friend of ours called Dempsey, Daniel and MacDaniel on Jamison Street in Detroit.

"It would be a pleasure just to be on his show. I see him every once in a while just to sit down and talk to him about his kid days. I run into him at the Circle Star--he called me up on stage. He said, 'Let's call up the master--the creator.'

"That made me feel good, too. No matter how long you been doin' this, nice things make you feel good when they're said about you."

On Hooker's recent tour he visited Florida--Miami, Jacksonville, Daytona Beach, Key West--and New Orleans. "I played at a real famous ol' place that Professor Longhair used to work called Thibideaux's. You've probably heard of Professor Longhair? They may call me King of the Boogie, but he started a lot of this stuff."

Just as the late pianist Professor Longhair 'invented' the romping boogie-woogie left hand, when Hooker leans forward in his straight-back chair and tantalizes his audience with a barrage of guitar chokes and hammerings, one could easily believe he discovered the blues guitar.

Hooker is proud of his backup band. "Don't forget to mention my musicians," he says. "The young musicians that play with me--the oldest one is the organist Deacon Jones. He's 42. It's a real, real good band with Michael Osborne on lead guitar, Tim Richards on drums, Kenny Baker on tenor sax and Larry Hamilton on bass.

"At 70, I'm not thinkin' about retirin' just yet. I may have to get on a cane or get on my knees and play. But as long as I'm able, I'm gonna do it. It keeps me kinda warm. I don't do it as much as I used to. I call my own shots. I tell my manager whenever I feel like goin' out. I let him know three or four weeks in advance and they start bookin'. They realize I'm not a spring chicken anymore.

"I've been thinkin' very, very strong about just producin' and then kick back and do something on my own once in a while.

"Ooooh, there are so many good blues artists out there now and they are serious. So many tryin' to do it. There are so many different groups that are so good. I'd like to give 'em a push. I'm goin' out and listenin' to more of them these days.

The phone rings; it's Hooker's daughter, who needs a ride home from the fast-food restaurant where she works. (He counts seven children. "Then I got some laying around that I don't know about," he adds with a laugh.)

There's time for one more question, about the origins of the blues. With a warm smile, the patriarch responds with a brief litany.

"Well, you're diggin' deep now. Where's the real roots? The real roots is ever since the world was born. The real roots of the blues was here when the world was born.

"The roots was here when they made man and they made women. The trouble started. The heartache started. Now how long ago that been, I don' know. But now that's the real roots. When I got here they was here and when I leave here they gonna be here."

With that, he pulls on one of his many hats, jumps into the Supra with custom plates that say LES BOGY, and, with a twist of the wrist, backs out of the driveway. He slides the transmission into gear, and his tail lights disappear down the subdivision street. There's bound to be a stop sign ahead, but the Boogie Man won't slow down before he has to.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Hooker at the Cabaret nightclub in San Jose in the mid '80s.

Hooker at the Cabaret nightclub in San Jose in the mid '80s.

A treasure in our midst for at least a couple of decades, John Lee Hooker left a lasting imprint on the sunny western hills of the San Francisco Bay Area, giving it stature in the world of blues music alongside Chicago, Memphis and the Mississippi Delta. He not only performed regularly at local venues like JJ's, the Catalyst and the Icon Supperclub and sometimes joined superstars on the stage at Shoreline Amphitheatre, he nurtured an entire generation of Bay Area blues artists.

Remember John Lee Hooker: On Sunday (July 8), JJ's Blues presents a barbecue and blues day for friends and musicians to celebrate the great bluesman's life and music. The event takes place at JJ's, 3439 Stevens Creek Blvd., San Jose. (831.243.6441)

From the June 28-July 4, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.