![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

First Degree

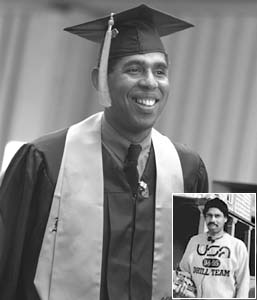

Christopher Gardner

Two years ago, Ramon Johnson was homeless, schizophrenic and living la vida loca in San Jose. Now he's graduating magna cum laude, thanks to a little help from the state, the feds and a church lady at St. Joseph's.

By Traci Hukill

LAST FRIDAY AFTERNOON Ramon Johnson adjusted his mortarboard, gave a final tweak to the two honorary stoles draped over his maroon gown, sneaked a puff of a friend's cigarette and joined the 32nd graduating class of De Anza College on the sweltering football field with its tents and folding chairs.

"Whoa--lots of honors," commented a fellow graduate, nodding at Johnson's gold stoles, one for honors at De Anza, one for membership in the prestigious two-year honor society Phi Theta Kappa. Most of Johnson's honors weren't even showing: the "magna cum laude" on his diploma at home, the National Dean's List membership, scholarships from Dare to Dream and De Anza's California History Center and a Faculty Association Scholarship Award.

These aren't the achievements of just another overcaffeinated undergrad. Two years ago, when Metro ran a story about the homeless mentally ill, Johnson was a big, slightly rumpled 37-year-old with a history of psychotic breakdowns rattling behind him at every step. Sexually molested at age 9, he started hearing voices that turned hostile after he discovered his mother's suicide at 14. After graduating from high school he fell into an all-too-typical cycle of drug addiction, rehab, mental breakdowns and suicide attempts. At the time of our first interview in 1997 he had been hospitalized in the mental ward at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center five times in 18 months.

Johnson spent his days cruising around downtown with his headphones on, writing songs in a notebook he carried in his backpack. Nights he spent at the Julian Street Inn in a room he shared with a dozen other homeless, mentally ill men. A cocktail of antidepressants and antipsychotics was holding his schizophrenia and bipolarism at bay, and he'd been off alcohol and drugs (mainly crack) for two months.

In spite of his easygoing charm and obvious intelligence, his dreams of getting housing and studying broadcast journalism at De Anza College seemed proof of a still-tenuous grasp on reality. The obstacles of no housing, no job and no money simply appeared too great.

But over the next two years, Johnson defied the odds and made the system work for him. He got housing through a federal program called Shelter Plus Care designed to help homeless, mentally ill people, drug abusers and AIDS sufferers get off the street, and with assistance from the California State Department of Rehabilitation, he enrolled in De Anza College. Shelter Plus Care paid for his one-bedroom apartment and the Department of Rehab paid his tuition. He checked in regularly with his social worker and counselors, creating a network of concern to catch him if he started to fall. Then he began taking the hour-and-a-half bus ride to school from his eastside apartment.

The first quarter he got three As and a B. The B, he points out humorously, was in Beginning Golf.

Intellectual Rescue

THREE DAYS BEFORE graduation, Johnson and I meet at the Campus Center at De Anza. He looks a lot different than he did two years ago. His hair is shorter, with a few wiry gray strands at the temples--the only indication he's about to turn 40. Other than that, he looks like a typical student: rangy, athletic frame (he used to play basketball and football), shorts, T-shirt, backpack. No Walkman this time. And his voice is the same, resonant and expressive.

Academic life has been tough. "By the end of the quarter I'm frazzled, I'm done," he says. "I need to sleep for a week, because by then I've just been all over the place. It's something I fight with all the time, keeping my focus.

"But I know my warning signs. If I'm not sleeping or eating right or my apartment gets messy, I know something's going on. That's the manicky part of me."

He had to drop a class one quarter because he was getting overloaded. Nothing new about that. Once in the early '90s when he was attending San Jose City College, he loaded up on 23 units in theater arts and marketing, acted in a play, hosted a radio show and played basketball regularly with his friends. "That's how manic I was," he recalls ruefully. Predictably, he burned out by semester's end and his grades were disastrous.

Besides meeting with him regularly and fine-tuning his medication levels, Johnson's psychiatrist helped him identify external barometers of his mental condition. Gradually, too, he's learned to resist the urge to take flight when he feels overwhelmed. His self-control has paid off. Johnson's professors have nothing but praise for him.

"He is an intellectual," observes David Howard-Pitney, a history professor who asked Johnson to teach a supplemental study skills class after Johnson aced his class. "He has a genuine interest and passion in history and historical sources. But what makes him extranormal is he's got charisma. At any given time I have four student instructors working with my students. He was easily the most popular among them."

Biology professor Leland Van Fossen concurs. "I think he was really thirsty for education," he remarks. "I've never seen another one like him."

Johnson volunteers once a week at St. Joseph's Cathedral in San Jose, steering frustrated people through the system. "A lot of the people I assist there are people I was with at Julian Street Inn," he says. "So I'm like a walking example of how the system really can work. There are things out there to help you, but you have to jump through a lot of hoops to get to that point in the system."

Patron Saint

AS WITH MANY PEOPLE WHO break out of homelessness, the key for Johnson was finding a powerful ally. In his case it was Sharon Miller, director of social ministry at St. Joseph's. Miller sponsored Johnson's entry to the five-year Shelter Plus Care program.

There's a waiting list for Shelter Plus, just as there is for Section 8, which serves all poor people. But Shelter Plus is awarded only to the most motivated: a candidate must show commitment to rehabilitation and know a program sponsor for six months. That means six months of keeping psychiatric and Alcoholics Anonymous appointments, staying on medication and, in Johnson's case, attending school--all while still homeless.

Before Miller or anyone else could help him, Johnson had to make a crucial decision to change. "Finally I just said, 'I don't want to live like that anymore,' " he remembers. But the world didn't leap to his aid right away. Until he met Sharon Miller, he was "on the list, always on the list"--for housing, for SSI, for general assistance--for everything.

"You have the resolve to go try to work the system, and the system sits on you," he points out, some frustration creeping into his voice even now. "One of the problems with the system is that the funds can be dried up at any time. So there's still that feeling that there's the puppeteer pulling your strings. You're not in control."

He's feeling some of the old exasperation again for a fresh reason. Two weeks ago he came home to a letter from the Shelter Plus Care program manager dated June 15 announcing that he needed to find another apartment by June 17. Johnson admits he knew he would be moving out of his apartment this summer (it's too expensive for the cash-strapped Shelter Plus fund), but claims the final notice was the first letter he'd seen. He's all too aware that without his carefully constructed network he could have wound up homeless again, at least for a little while--and the timing would have been terrible.

"That would have been great," he speculates dryly. "Here I am, an honors student graduating, and I'm living under the bridge."

As Johnson's case manager, Sharon Miller stepped in and made an arrangement for St. Joseph's to cover his rent through the end of the month. Then she scrambled to find an apartment whose rent did not exceed the federally established fair market value of $922. "It was so tough to find something that was decent," she marvels. She did, though. On July 1 Johnson will move into a new place near Spartan Stadium.

"Those first two years of housing really are a challenge," Miller says. "Then it just becomes routine. By the fourth year you're really trying to wean them off services."

Jeff Rowe, the county's new homeless services coordinator and the man in charge of Shelter Plus Care, acknowledges the seriousness of the disconnect between the actual cost of rents here and what the feds are willing to pay.

"It makes it difficult for us to run an effective program, to be honest with you," says Rowe, who is heading a delegation of Bay Area homeless coordinators going to Washington to lobby for more money.

For Johnson, the combination of stable home base, regular contact with mental health specialists and staying on his medication has prevented him from veering off in a blaze of self-destruction. He knows he's not out of the woods yet. "I'm not perfect," he says. "I still go up and down, it's just that my ups and downs aren't as drastic." And his singular focus on academics has left him lacking a social life--which to someone like him can be insurance against disaster, just as his network of counselors is now.

As Johnson approaches the two-year mark and prepares to leave the comforting environment of De Anza, he seems unstoppable. Although disabled students have been a priority at De Anza since the school's inception in 1967 (a fleet of vans used to chauffeur disabled students from other community college districts), and although San Jose State is less "user friendly," in Johnson's words, he's looking forward to completing his bachelor's degree there and going on to a master's. After that, he'd like to teach at a community college. I am reminded of what happened the last time I fretted that Johnson was setting himself up for disappointment with too lofty a goal.

As for Johnson himself, he's set to keep on track and feels a responsibility to give something back to the system. "Let people know it's possible to go from the outhouse to the penthouse," he says. Then he hurriedly corrects himself. "Well, it's not the penthouse yet, but the elevator's going up."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Getting Better All the Time: Ramon Johnson made the jump from life on the streets to the college campus, where he graduated with honors.

Getting Better All the Time: Ramon Johnson made the jump from life on the streets to the college campus, where he graduated with honors.

From the July 1-7, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.