![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Ice Dream Man

By Michael Learmonth

A COOL FOG RISES off the 12-inch-square tiles of dry ice. Prospero Hernandez, 29, grabs one, breaks it in half quickly and slips both halves into plastic bags and ties them. "Se quema"--it burns--he warns as I bend down to pick one up. He places the blocks inside his cart and then dumps in ice chips.

It's 1:30 in the afternoon, and San Jose has been cooking in the sun for a good three hours. School's out, wading pools are full and children sit hot and bored on neighborhood porches. These are prime cart-pushing hours.

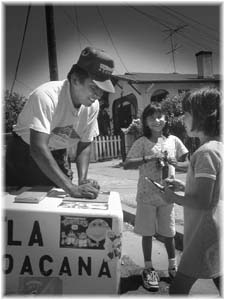

Hernandez leaves La Michoacana Ice Cream on Union Street shortly before 2pm, his cart laden with 75 americanos, U.S.-style ice cream bars, and 75 mexicanos, Mexican paletas or flavored ice bars of coconut, tamarind and strawberry. He's not 10 feet out the door before he makes his first sale, three bars to a mother and two children waiting inside a sweltering car at an automotive garage. Everything in the cart costs a dollar. Hernandez takes his first three in his right hand and crosses himself. Then he mumbles a prayer and crosses the cart.

Every afternoon, Hernandez takes to the streets until eight in the evening. He makes 50 cents on the dollar for every paleta he sells--enough to make rent and send $200 a month home to his four children in Michoacan, Mexico. On a good day, he sells 140 paletas and takes home $70. Most days, though, are like today: After eight hours and 10 miles of hot concrete, Hernandez takes home $31.

Hernandez's route takes him south on Almaden to San Jose Avenue. Then he turns east and begins winding though the neighborhoods until he gets to Spartan Stadium, where he turns back at the end of the day. There are more lucrative routes--in downtown San Jose or Milpitas--but Hernandez feels safest in the predominantly Latino neighborhood. He stays away from main roads because, like most paleteros, he is unlicensed and risks a $278 fine every time he hits the streets.

In order to operate legally in San Jose, paleteros must first get a business license that costs $154.50. Then a county health department sticker for $107. After that, they must undergo a background check, fingerprinting and a drug test at the police department for a photo identification card that costs $218. That's more than Prospero Hernandez makes in two weeks.

"The majority of the vendors are not carrying permits," says Officer John Carrillo of the San Jose Police Department. Most of the paleteros, he says, come from Mexico for the summer to work behind the cart for a few months before returning home.

The police background checks were mandated by a city ordinance passed in 1995 after two paleteros were arrested in San Jose for rape and sexual assault.

"What occurred in 1995 was an example of a criminal who was involved in selling ice cream to kids," Carrillo says. "Give credit to other paleteros who helped in the investigation."

The only form of identification Hernandez carries is an expired voter ID card from Mexico. One day he would like to become a legal resident and perhaps a citizen and get a job working for the U.S. government. For now, he and his wife, who works at a Taco Bell, scrape by living in a $600 two-bedroom apartment on Willow Street with six other people. Hernandez shares a bedroom with his wife and her mother and sister.

At 3:15 in the afternoon, Hernandez sells his 21st and 22nd paletas to a young woman walking with two children on Alma Avenue. He passes Le's Market at Sanborn Avenue and stops still. A police cruiser is parked around the corner, and a female officer wearing wrap-around sunglasses is busy rousting an indigent woman from the parking lot. She gestures to Hernandez's cart and offers to buy the woman an ice cream if she will move on.

"I'll buy you one, Doris," she says. "I really will."

"I don't want yer poison," Doris bellows, reluctantly vacating her shady spot.

The officer smiles and shrugs at Hernandez. "I would have bought her one," she says, before driving away.

Hernandez lifts his cap and wipes his brow after his brush with the law. Officer Carrillo notes that paleteros are often crime victims because they walk alone and are almost always carrying cash. By 4pm, Hernandez has $25 on him and $5 in food stamps. While his boss at La Michoacana doesn't take them, he will use them to buy food for himself.

"Someday, I would like to buy a house in this neighborhood," he says, walking down Ford Avenue. "A lo mejor"--hopefully.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Popsicle vendor gets on the stick in his quest for a piece of the American economic pie

From the July 24-30, 1997 issue of Metro.