![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Crumb for Dummies

'The R. Crumb Handbook' chronicles 45 years of graphic outrage by the man who didn't come here to be polite

By Richard von Busack

TOM WOLFE called it "The Boho Dance"—a since-extinct dance craze described in the author's art-crit book The Painted Word. This number is performed almost exclusively by artists and those who want to be artists. As proved by The Crumb Handbook, by R. Crumb and Peter Poplaski—essentially, Crumb for Dummies—Robert Crumb, at 62, has lost none of his terpsichorean ability.

The Boho Dance is a twirl of rebellion, followed by capitulation. The best example, Wolfe writes, could be seen in the social life of artist Jackson Pollock. Drunk at one of Peggy Guggenheim's parties, he would cap the evening by peeing in the fireplace just to show his contempt for the wealthy bloodsuckers who bought his paintings—but (emphasis Wolfe's) he'd be right back the next Saturday night.

To the boho, contempt follows the lure of fame, like a profound hangover after a night of serious drinking. And thus the cycle continues.

"I'm not here to be polite!" the now white-sideburned Crumb says, scowling from a self-portrait on the cover. The R. Crumb Handbook digests about 45 years of work by the internationally famous artist/underground cartoonist and throws in some history, commentary and miscellany. The print job is slick, with finely done digital color. The portability of the volume comes at a sacrifice of size for the drawings. No doubt a few of the originals have disappeared or disintegrated or been sold, so a few of the repros come from blurry pulp.

Those who have followed Crumb must regret the loss of some bit of favorite work. I'm in the minority, but I think Crumb's most fertile years were little-followed compared to his happy hippie heyday.

Crumb's soulful brush-and-ink illustrations for Harvey Pekar's memoirs in the American Splendor comics rank among his masterpieces. There, Crumb summed up distant lives in the post-industrial solitude of Cleveland. He captured small, good things, like the essential rightness of a loaf of fresh bread bought at an old mom-and-pop bakery.

When Crumb was making cartoons for Weirdo comics in the 1980s, his firmly held democratic illusions were being shaken by the popularity of the Reagan regime. Just how much Crumb had once believed in the vox populi can be seen on the back cover of The R. Crumb Handbook.

There is a late-'60s screed that urges the amateur to pick up a pen and join him: "'Art' is just a racket, a HOAX perpetuated on the public by so-called 'Artists' who set themselves up on a pedestal." Only two decades later, Crumb frets over one of his posters for a gallery exhibit in Europe: "But is it art?" Wasn't it always? And why does he care now?

Crumb's scintillating work for Weirdo ranged from blistering sexual confessionals to eerie illustrations of German fairy tales. Finally came his goodbye letter to America, a howling parody of white-supremacist dogma, so picture-perfect it was taken seriously by a few lame-brained skinheads.

Still, the scandalous Crumb is well represented in The R. Crumb Handbook. The splash page, The Family That Lays together Stays Together (1969), from Snatch Comix No. 2 is a lethal mix of the bulbously cartoony and the incendiary. The even more infamous Joe Blow, also published that year, is exactly what you'd want to anonymously mail to family-values hotheads: six grand pages of incestuous outrage. Try this kind of approach today, and you'll be saying, "Good morning, judge."

In a way, these cartoon enormities are a tribute to the miserable years Crumb spent as a commercial artist at Cleveland's American Greetings. Imagine the man, meeting the company's strict dress code and toiling for an editor named Tom Wilson, "the creator of that fuckin' Ziggy," as Crumb later described him.

"They trained me to develop a drawing style that was 'cute,'" Crumb grumbles here. But the artist had his revenge. When Crumb drew plump, wrinkled, bristly genitals, the drawings were always had such infuriating impact because they were so sweet.

Besides a few recent pages from his sketchbook, the new material is scarce. There are only four drawings done after the year 2000. His latest piece, from 2002, is The Heartbreak of the Old Cartoonist, about feeling too old and tired to work. In the flyleaf, Crumb does a timeline that claims that, around the year 2000, his "sex drive tapers off slightly." Supposedly, Aristotle said that after his sex drive ran out, he felt "like a slave liberated from a cruel master"; has Crumb similarly been liberated by age?

The artist has always been pushed by something. First it was his brother, Charles. A pleasant discovery here is a late-1950s "Fuzzy the Bunny" story. It states the Crumb brothers' dissatisfaction with the blandness and predictability of comics—an early critique that would be picked up by hundreds of ink-slingers 10 years later. Later, in his most celebrated years, Crumb derived energy from being a soldier in what he calls "The Army of the Stoned."

Until recently, Crumb's work has been fired by his volcanic libido, as he drew those unmistakable big-legged Crumb women, with their watermelon-sized rumps. (In this book, Crumb includes a photograph of the mother of all of them: Irish McCalla, TV's Sheena, the Xena of 1950s television.)

So, what now? It's hard to argue with Crumb's desire to enjoy the good life in the south of France. And yet the mammoth ugliness and ferocity of life in the United States begs to be met with the vitriol of Robert Crumb.

That's what I wish Crumb was doing, instead of coasting on ancillary merchandizing and airing old beefs about the cost of fame. Considering Crumb's vociferous public moaning about Terry Zwigoff's Crumb documentary, it's odd to see two different versions of that film's poster reproduced, as if they were trophies. (Not to mention three different posters for Fritz the Cat, the movie yentzed out of him by Hollywood producers—an old lament that he rehashes here.) Artists who work their asses off might resent Crumb's complaints about the burden of fame. As they say, the song about "Imagine no possessions" could only have been written by a man who lived in a $3 million mansion.

Watching this old dancer of the Boho Dance is like watching a talented clogger. It's a different dance today, as American Idol watchers know. It's rare you'll see today's artists writhing because of too much attention. Still, when he sits down and does it, Crumb's work is as good as it's ever been. No, better.

Incidentally, an attached CD, R. Crumb's Music Sampler, gives an idea of Crumb's other life as a musician, performing novelty songs, old-timey tunes and a couple of French musette waltzes. Is this the secret of Crumb? The man who brought the 1960s together in graphic art—just as Bob Dylan brought the era together in music—might be happiest being remembered as a song-and-dance man.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

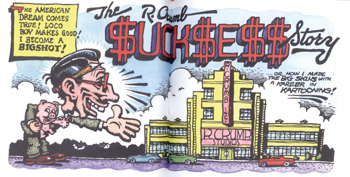

Will Success Spoil R. Crumb?: The '60s iconoclast confronts Mammon.

The R. Crumb Handbook, by R. Crumb and Peter Poplaski; MQP; 440 pages; $25 cloth.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the July 27-August 2, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.