![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Photograph by Skye Dunlap

Rebels With a Cause

Skateboarders say that if the city of San Jose builds a skate park, they will come. Until then, they'll continue to skate like outlaws.

By Jessica Lyons

Nate DelGrande doesn't see things the way I do. The small paved lot at Go Skate on Almaden Road is a jungle of sorts. Nate's eyes see the edges on curbs, the angles of bench seats, the tempting stair railings and buckling sidewalk. "I see a planter, and think: 'I could spend two hours at that planter having fun,' " he says.

All I see is a clay pot.

For Nate, Go Skate's 22-year-old manager, everything solid is a surface, and every surface is skatable. Rail sides are good for sliding, cement blocks and benches work for grinding, and cracks are good for flips. Today, however, Nate's not skating, and it's killing him. He's been sidelined for nine months because of knee surgery, the result of one too many run-ins with the ground.

Behind the store, Noah Baxter and Luis Martinez are on a mini-ramp playing PIG, the old driveway basketball game, now translated into skateboards and a wooden trench. Passersby are obstacles. Pedestrians--especially reporters and photographers--are fair game.

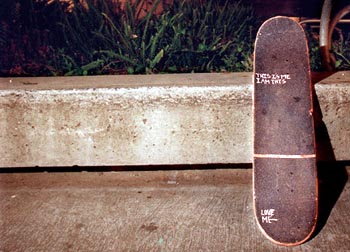

Noah, a scrappy 26-year-old with intense blue eyes, skates hard. He's dripping sweat by the letter P. Noah's a caricature of himself, the misunderstood outlaw punk. Falling doesn't hurt, but he does punish the board when it lets him down, banging it against the nearest blunt object--a cement wall, a metal pot or his head. He doesn't have a car, a driver's license or a home. Just a bicycle and a Black Label skateboard. Eight words are etched into the top of his board: "This is me, I am this." Then, down at the bottom, "Love me."

Noah brags he's one of the surviving few who hasn't gotten ticketed for skating downtown. But I don't think he would mind terribly much even if he did.

"I skate everywhere," Baxter says. Everywhere except San Jose skate parks--the city doesn't have any.

"Streets, curbs, rails," he says. "Downtown a lot. But you can't skate downtown in just one spot. You get chased. If you keep moving you can go a night without seeing the cops. You have to keep moving."

No surface is off limits.

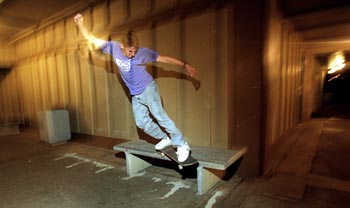

Board Members: Matt Rogers flies up and over a concrete bench.

Crime Seen

THE CITY OF SAN JOSE, however, disagrees--the sport was outlawed more than a decade ago. Skateboards are loud, and many city officials consider their riders to be rebels, vandals and bandits. In 1988, the San Jose City Council banned skateboarding in about 50 square blocks downtown, as well as in--or on--any city-owned buildings, parks and structures. In 1995, downtown Willow Glen followed suit. The council made it illegal to skate along Lincoln Avenue. Most Bay Area cities have a similar ban in place.

Skating in San Jose is punishable by a $75 fine, and that's just for the crime of skateboarding. Vandalism citations can run to thousands of dollars, and even carry jail time, depending on the amount of property damage.

"I've seen scratched-off paint on curbs, deteriorating concrete, and some cement formations that they use are starting to chip," says San Jose police officer Rubens Dalaison. "They increase the neighborhood blight issues, they put scratches on handrails and poles, they damage foliage."

Skateboarding can also cost skaters their boards, which, according to local skateboarders, is an everyday occurrence.

Nate's gotten four skateboarding tickets in two years. Nineteen-year-old Miguel Duran, a tall, polite kid in baggy jeans and a plaid button-down shirt, has gotten three.

Skateboarding has its limits at non-downtown city parks, too.

"We don't like them in parking lots, we don't like them near community centers, we don't like them in playing courts," says Jim Norman, deputy director of the city's Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services Department. "As a means of transportation, skateboards are under normal laws and uses of a sidewalk, but in interior park facilities, tennis courts, community centers, they're not allowed."

Skating on school grounds is OK--sort of.

"It's just like walking as a pedestrian," says Sgt. Todd Martin, of the SJPD crime prevention unit. "Unless school officials have put up signs that prohibit skateboarding on school grounds, [it's OK to skate there, but] of course if skateboarding is causing any damage to the school grounds, then it's damaging public property--vandalism. Or if you're violating another law, like a curfew law." Or if neighbors call and complain about the racket from plastic wheels grinding on pavement. "Then it's a disturbing-the-peace violation," Martin says. "Anytime anyone is allowed on school, you're also allowed on school grounds with a skateboard."

So what's a skater to do?

"We need a skate park around here," says 17-year-old Quynh Le, who's paid two tickets for skating downtown. "You go downtown expecting to get chased by cops. You get used to it. Give us a park and leave us alone."

Park and Ride

THAT'S STARTING TO SOUND like a good idea to local politicians. Councilman John Diquisto, who represents west San Jose, is sympathetic to the skateboarding cause. Diquisto's aide, Dawn Wright, says the councilman is looking to partner with a local skateboard firm and build a facility at Butcher Park.

"We think if we were to partner with somebody, we could build something really nice with dips and bowls," she says. But without a partner, the funds aren't there.

Central San Jose's councilmember, George Shirakawa Jr., says he hopes to pull money from next year's District 7 budget to build a neighborhood skateboard facility near Stone Gate Park--a community where the kids have been active in promoting a skate park.

"It won't be a large citywide facility--I don't think the neighbors would want that--but the kids need someplace to go," he says. The skateboarders themselves will help to design the park, he says.

"One, they need to own it, and two, they need to get involved in the process."

But neither councilman expects to see any concrete poured sooner than a year or two from now.

If San Jose says skateboarding is a crime, than the city needs to offer an alternative, many argue. Most councilmembers say they support the idea of a free, citywide skate park, but money stands in the way. Parks are expensive to build, and more expensive when people get hurt.

"We would like to build a park," says San Jose Councilwoman Charlotte Powers, who represents the Santa Teresa/Edenvale area. "But we haven't been able to work out the insurance issues. Otherwise I would be plugging for one."

State lawmakers in 1997 declared skateboarding a hazardous activity, like rock climbing, which means cities cannot be sued for injuries sustained by people 14 and over who skateboard on city property. But according to city attorney Joan Gallo, the law has too many loopholes.

"From the liability perspectives, this bill gives very little protection to cities," Gallo says. "It only protects cities against people 14 years old and older; it only protects cities if the skateboarders are doing a stunt or trick or luge skateboarding; it only protects cities if we require skateboarders to wear protective gear. Fortunately, it doesn't say exactly what color T-shirts they have to be wearing."

Meanwhile, some skaters build backyard ramps--the only sure way to avoid tickets and the police. Others take their chances at city parks and hope when they see the black-and-whites rounding the corner, they can outrun them. The chase is part of the allure.

"I'd be stoked if there was a skateboard park around here, but I'd still skate downtown," Noah says. "Skateboarding is not a sport. You can't confine it to a football field or a tennis court."

Local skaters say if the city builds a skate park, they will come, but with the lack of open space in San Jose, plans for a park are still in the early mixing stages--as unstable as freshly poured cement. San Jose's Jim Norman is not making any excuses.

"Sure we're behind--we're behind in keeping up with the general open space, we're behind in ball fields for soccer, we're behind in swimming pools," Norman says. "San Jose grew faster than we were able to keep up with, developmentwise."

With the lack of open fields and parks, however, a paved paradise for skateboarders takes a back seat.

"When I have a choice of putting in two to four acres of turf for a variety of uses, versus a skateboard park with limited use, it always makes it a question of priorities," Norman says. And in San Jose, a skateboarding park does not top that list.

Designs are likely to be drawn before next July, Norman says, but San Jose still wouldn't see a citywide skate park until late 2000, maybe even 2001. First, the city needs an open two-acre site to house the concrete ramps, stairs and rails. Norman estimates a park would run $175,000 to $200,000--and that's for a small-scale park. The 15,000-square-foot one the city of Santa Clara recently built cost $400,000.

In the meantime, skateboarders say, they will continue to frequent schoolyard staircases, parking lots and downtown parks--and skate like hell when the cops on horseback ride into view. They're too impatient to wait.

Wheel Attitude

BRYAN ADUDDELL, 22, only skates in his backyard. Three years ago, he built a ramp from plywood. It's 4 feet tall, 16 feet wide and 32 feet across. But it's a work in progress--next month, it will reach 6 feet high, he says.

"I'm too old to get chased by cops," he says. "I'm not running from nobody."

Bryan, Noah and Miguel warm up on the ramp, while Nate watches. Miguel looks slightly out of place on the ramp. Nate says that's because he's a street skater, not a ramp skater. Bryan, on the other hand, is at home. He skates with a hard-core edge, doing flips and slides from the extension.

Watching his friends skate, Nate can't stop the catcalls and whistles. His normally cocky grin morphs into a smile of pure appreciation. He wants to join them, and it's Noah who gets him psyched, he says.

"Other skaters can do that to you, especially when they're better than you." He's anxious to be back in the game.

He points to Noah on the far end of the ramp. "It looks like he hurts the ramp," Nate says. "It's just crying."

Once they're in motion on the skateboards, they all lose some of their charm--charm that borders on sweetness when they're standing on their own feet. It's hard not to admire such depths of passion, but the attitude can also turn to arrogance and paranoia. It's the attitude that gives skaters a bad name and gets them into trouble with the cops. Noah's "Love Me" slogan on his skateboard is a demand, not a plea.

The board wheels are loud, it's late and Bryan's parents want some peace. When Bryan's dad yells "Eight more minutes!" from inside the house, all courtesies are kicked to curbside. Skating takes priority over anything else--including getting photographed for a newspaper article.

"I don't have time for this," Bryan says, narrowly missing the photographer. "I only have eight minutes."

Eight minutes are up, so we move out and head to a new location. The skaters are hesitant to reveal their skating grounds to an outsider--it could mean more police activity and more fines, they say. No one's up for skating the South Side Bump, a protuberance in the sidewalk created from buckled asphalt in south San Jose, so we head to Santa Teresa High School instead.

While Miguel and Noah skate the cement bench in the high school courtyard, Nate shows me the injuries that keep him from joining in. He lifts up his pant leg, exposing a 6-inch scar running along his knee. But there's more. Nate turns his arm over, pointing to a gash that runs almost from the back of his wrist up to his elbow.

"I broke my radius bone, and my elbow was sticking out 2 inches," he says. He was doing a trick called a backside lip-side, his board shot out from behind him, and he landed on his arm. Now there's metal plate under his skin.

He shows me a faded mark on his pointer finger. "I even ripped my finger open trying to clean a bang under my skateboard. No matter how many times you do a trick, there's always that one time it will go wrong," he says. "Sometimes you can tell, sometimes you don't know until after you've tried it. It's a fine line between pleasure and pain."

The passion seems mixed with masochism. Sooner or later every skater goes down. Helmets can protect against head injuries, but pads won't stop a wrist bone from breaking through the skin, or a knee from being twisted the wrong way.

That's what separates them from me. I'm afraid of pain. To skateboarders, every obstacle, every fence, staircase or broken concrete surface presents a temptation--a challenge they'll try to best. Climbing the fence slowly, sneaking into the schoolyard, I'm afraid of falling. I flinch when one of the skaters hits the ground. They just howl and ride away.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

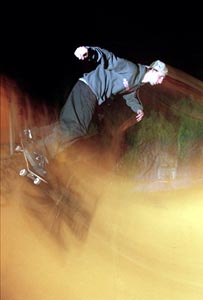

YIMBYism: Todd Morgan skates a half-pipe in a friend's backyard, one of the few places he can legally use his board.

YIMBYism: Todd Morgan skates a half-pipe in a friend's backyard, one of the few places he can legally use his board.

Photograph by Skye Dunlap

Photograph by Skye Dunlap

From the August 26-September 1, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.