Gravity's Pull

Tracking Thomas Pynchon through space and time

By John Yewell

NOT MANY PEOPLE would leap out of a window to avoid being photographed. But once, many years ago, when a reporter caught up with Thomas Pynchon in a Mexico City hotel, the author did just that. Pynchon is so intensely private that his very existence has been called into question. Sightings are rare and only a couple of old photos of him are publicly known. Although his New York City home has recently received a fair amount of press, his whereabouts continue to be a game of "Where's Waldo?"

Writing about any author's life is by definition invasive. In the case of Pynchon, one ends up running a gauntlet of his cultish followers, who are conspiratorial--dare I say Pynchonesque?--in their defense of the writer's predilection for privacy. The most intense see themselves as a breed of Internet knights who, in loose electronic confederation, discourage the inquisitive. At the same time, many devotees are in the hunt themselves and live for an encounter with the man, even though they have only a general idea of his life, appearance or whereabouts, and may already, for all they know, have run into him. Pynchon's truest friends, the real-life acquaintances who share his world, are simply silent on the matter.

Local residents familiar with Pynchon know of his purported residence in Aptos. Over the last 20 years, I have caught occasional vicarious glimpses of his life here, and I can attest that its existence is more than mere rumor. Through various postal acquaintances (I was a letter carrier for seven years), I've kept rough tabs on the man. My interest began with respect for his work, but gradually grew into something more personal as I discovered old ancestral connections between his family and mine.

Genius Is Its Own Reward

THOMAS RUGGLES PYNCHON was born May 8, 1937, in posh Glen Cove, New York, just down the road from my father's Port Washington home. Pynchon studied at Cornell from 1953 to 1959, interrupted by a two-year stint in the Navy that provided him with much of the material used in his 1963 novel, V, which that year won the Faulkner award.

His next novel, The Crying of Lot 49, appeared in 1966, to be followed by his chef d'œuvre, Gravity's Rainbow, in 1973. (When he won the National Book Award for GR, he sent comedian and self-styled "World's Foremost Expert" Prof. Irwin Corey--who delivered a bizarre, rambling speech--to accept it for him.) There followed a collection of his early short stories--Slow Learner in 1984--and two more novels: Vineland in 1990, and Mason & Dixon last year.

Gravity's Rainbow is a gargantuan and gothic book, so sweeping in its scope and impact that it has been referred to as the American answer to Joyce's Ulysses. While the debate among the literati over Pynchon's genius is virtually settled (the pro-genius side is way ahead on points), not everyone agrees. Pynchon recently failed to land a single book in the Modern Library poll of 100 best novels of the 20th century, despite critical acclaim and a passel of literary awards. He is not an easy read--his prose is dense but rewarding--and he has particular appeal to a certain type of late-20th-century techno-sophisticate not well represented at universities or on stuffy book club review panels.

The Past as Prologue

THE AUTHOR'S PROGENITOR, William Pynchon, came to America in 1630, 10 years after the Mayflower, as an assistant to the new colonial governor, John Winthrop. Also in that fleet was William Hathorne, great great great grandfather of the novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, and, through my mother (née Harthorn), my great great great great great great great great great grandfather.

In 1651, William Pynchon managed to get himself into hot water with the ecclesiastical authorities. His book, The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, a criticism of the Calvinism of the day, caused a scandal, prompting the General Court of Salem to order the book burned. One of the two (out of six) court magistrates who voted against the censure of Pynchon was William Hathorne.

Eight years later, William Hathorne, then 53, and William Pynchon's son John, 33, traveled together to the Dutch fort at present-day Albany to propose a plan to open a cattle operation in western Massachusetts. The ostensible object of the venture was to supply the fort with beef, but the Dutch governor in New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant, rejected the plan. He understood correctly that it was a ruse to establish an English presence closer to the lucrative Hudson River fur trade. In Gravity's Rainbow, Pynchon lends these distant New England roots to his character Tyrone Slothrop.

Finally, 200 years after the burning of William Pynchon's book, a curious literary echo of the Hathorne/Pynchon connection would reverberate in New England.

William Hathorne's son, John, himself a magistrate but lacking his father's tolerance, was one of the most bloodthirsty judges of the Salem witch trials in 1692. Family legend holds that John Hathorne's actions resulted in a family curse, courtesy of one of his victims.

When Nathaniel Hawthorne (he added the "w" to his name to distinguish himself from his great great grandfather John) published The House of the Seven Gables in 1851 as a kind of atonement for the sins of his infamous ancestor, he chose the "Pyncheon" name as a stand-in for the Hathornes. The resulting portrait was so unflattering that the author later wrote a letter of apology to the Pynchon family.

Close Encounters

PERHAPS IT WAS appropriate that my first brush with Pynchon's work was in the form of a graffito--appropriate because Pynchon's characters so often communicate through unconventional means, be it the subversive underground contra-postal cabal known as W.A.S.T.E. (We Await Silent Tristero's Empire) in The Crying of Lot 49, or by the perverse telemetry that connects the character Tyrone Slothrop of Gravity's Rainbow to the impact pattern of German rockets, which mysteriously and cartologically mirror his London sexual exploits during World War II.

In 1974, I was in my second year at UCSC, and as a fresh-scrubbed undergraduate lit major I had managed to avoid Pynchon's growing legend. So when I walked into a bathroom at Stevenson College that day and let my eyes settle on the urinal wall, it was the excitement of learning a German obscenity that first struck me:

"Fickt nicht mit Rocketemensch" (Don't fuck with Rocketman)

The reference had nothing to do with Elton John's single "Rocket Man," which had hit the record charts two years before. This Rocketman, and the specific phrasing of that injunction, is one of many poses Slothrop briefly adopts in GR in a vain effort to avoid the guided missile-like destiny to which he is condemned. It was not long after that that I finally stumbled on Pynchon's books.

My first significant "encounter" came a few years later. It was early 1977, my last year at UCSC, and I was working as a campus projectionist for student-sponsored weekend movies. One night a friend, who had graduated some years before and gone to work for the post office, came rushing into the projection booth with a photocopy of a piece of mail. It was addressed to a literary agent in New York, but it was the return address that had caught his eye. It was from Thomas Pynchon.

Who Is That Masked Man?

IN 1983, my post office friend called to report on the most remarkable encounter yet--this time in the flesh. A tall man, perhaps 6-foot-1 or 6-foot-2, with salt-and-pepper hair, had come to his window that day to send his tax returns in two certified letters. After the customer had filled out the forms, my friend noticed Pynchon's name on them.

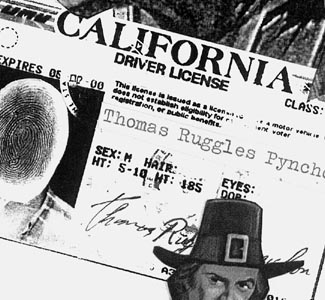

My friend looked up in surprise and, with a knowing look, asked the customer, finally, "Really?" Pynchon smiled back and said simply, "Yeah." He then produced his social security card as evidence, on the condition that my friend swear never to reveal his middle name. "Ruggles" is apparently a sore point with him, though it has been common knowledge among students of his work for many years.

After that encounter curiosity finally overcame me. One weekend a short time later I drove down from Palo Alto to check it out.

The home is tucked away in a remote area, a row of mailboxes on the road nearby. After determining I had the right house, I approached and knocked, and the door was opened by a young woman. When I asked if Mr. Pynchon was at home, she responded without betraying the least suspicion of my intentions.

"No," she said, "but he should be back soon. Can I take a message for him?"

I thanked her, declined and left, but that brief exchange confirmed a couple of things to me: one, that the address checked out, and two, that there was no praetorian guard protecting the author.

This was about the time Pynchon was putting together his collection of short stories, Slow Learner. His next novel, Vineland, might only have been a gleam in its author's eye, but there was much speculation after the book appeared seven years later about where it was set. One theory favored the Eureka area, but those familiar with Pynchon's movements recognized Santa Cruz County.

Then, in 1996, another friend ran smack into him. While working as a clerk for a local charity, a grayer Pynchon came into her workplace to donate some books. She realized who he was after he filled out a receipt for the goods and produced a California driver's license to confirm his identity. (Somewhere in the archives of the California DMV is a rare photo of Thomas Pynchon.) He was gracious, she says. Regretfully, she did not manage to hang onto any of those donated books, with whatever notes he may have scribbled in them. Somewhere these gemlike tomes sit innocently on bookshelves, guarding their own secrets.

The disposal of those books may have been a sign that he was preparing to spend less time here. Though I've kept a weather eye out for him, the word in the Pynchon electronic diaspora is that the author doesn't spend as much time in this area as he used to, living now in New York with his wife and agent, Melanie Jackson, and their son, Jackson.

Saving Pynchon's Privacy

SEVERAL RECENT BOOKS and articles have raised important questions about the privacy of literary figures. In the December 1997 New York magazine Nancy Jo Sales relates how she successfully tracked Pynchon to his Manhattan home and trailed him for a few days. The article did not divulge his neighborhood or address, and only the grainiest of photos shot from angles that revealed little about Pynchon's appearance appeared with the piece.

In his book Subterranean Kerouac: The Hidden Life of Jack Kerouac, Ellis Amburn, Kerouac's editor, reveals details about Kerouac's alleged bisexuality that Kerouac himself chose not to divulge during his lifetime. In Joyce Maynard's just published book, At Home in the World, in which she discusses her early years with J.D. Salinger, she says that when people find out she lived with a famous author they always try to guess who he was--and their first guess is usually Pynchon.

Thanks to the mystery surrounding them, Salinger and Pynchon are often compared--one writer, John Calvin Batchelor, tried to make the case in the now-defunct SoHo News that Pynchon is Salinger. But it is their differences, to my mind, that are most instructive in dealing with the thorny question of invasion of privacy. Unlike Pynchon, Salinger is a recluse, holed up like a fugitive at his compound in Cornish, New Hampshire, and held at bay by curious onlookers, virtually inviting scrutiny. Whereas Salinger is militant about his privacy, Pynchon--thanks to his ability to avoid the paparazzi--moves among us, protected from the hordes as long as his address and image go unpublished.

Sales quotes literary agent Chris Calhoun saying that Pynchon "is not at all disingenuous about it [privacy] like Woody Allen, who says he's shy but then can be found at Elaine's with the Rolls-Royce parked outside." Of course, Woody Allen is a good deal more recognizable than Pynchon, but Sales reinforces her point elsewhere by quoting Pynchon friends who explain that, while his privacy is guarded, he is friendly to strangers when flushed out--he simply abjures celebrity. Needless to say, Pynchon does not make public appearances.

However, in recent years, as his fame has grown, more cracks have appeared in the invisible wall around him. After Mason & Dixon came out, CNN sent a camera crew to his Upper West Side street, and found him all too easily. According to a recent article by David Bowman in Salon, the Internet magazine, a Pynchon fan at NBC took the CNN tape, electronically enhanced it, and produced fairly clear images of the man. I don't doubt we can expect more of that in the future.

To reveal his address or publish his image would, I agree--against all normal journalistic impulse, I might add--be gratuitous. It will be a more bloodless gumshoe than I who chooses to help put an end to that aeriform existence. Perhaps I would think differently of the matter if Pynchon were making a point of hiding or, like Salinger, spurning the public. But he isn't. The address of the Santa Cruz County house in which he stays is even listed under the owner's name in the phone book.

Live and Let Live

'FROM EVERYTHING I KNOW about Thomas Pynchon," Pynchon expert Stephen Tomaske wrote on one of the Web sites devoted to the author, "he seems like a nice guy, someone with above-average decency. Can't we just leave him alone?"

Well, no and yes. Like it or not, he is a public figure, and we can admire his success at maintaining his privacy--and honor it--while forgiving ourselves our curiosity about his life.

What drew him to this area only he knows, and he's not talking, at least not publicly. But for two decades Santa Cruz County residents have had Thomas Pynchon among them. The media circus that would have resulted from exposure certainly would have put an end to it, of course. I, for one, am content to have had him around on his own terms. There is a certain simple satisfaction in knowing that I might have stood behind him in line at the post office.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Illustrations by Winston Smith

From the October 1-7, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)