Suburban Fright

Roll Reversal: The rise in status of Silicon Valley's high tech industry, coupled with the popularity of San Francisco lifestyles has fueled what a Caltrain worker calls the "reverse commute."

'Reverse commuters' think Silicon Valley is a nice place to visit from nine to five, but--God forbid--not to live

By Ami Chen Mills

Here come the waking dead. Stiff-limbed zombies in hiking boots or dress shoes, bleary-eyed, blinking against the cruel morning sun. They come in black leather jackets and artsy earrings. They come in pressed suits, pushing bikes, their pant legs stuffed in their socks. They come clutching aluminum Thermoses like protective talismans, as well as rolled newspapers, laptops and antique briefcases; in their fleecewear, in their tennis shoes, in their conch-shell necklaces.

They are the hip techies. A growing group of the young and the restless who have shunned the suburbs to live a twenty- or thirtynothing existence on the streets of San Francisco. Still, they draw their lifeblood (their salaries, that is) from the seemingly bottomless well of wealth that is Silicon Valley.

They come this morning and every weekday morning--unless it's a telecommute day--to the Caltrain station at 22nd Street at the bottom of Potrero Hill in San Francisco, embarking on a round trip that can take as long as five hours a day.

In the noncommittal light of early morning, they stand at the station, silent and stunned, somber mourners of their former, sleeping selves, barely vertical until the 7:30am express train rumbles in to dock. Then they shuffle toward the closed train doors, humble pilgrims approaching Mecca. They wait, eyes cast upward. Then the doors slide open, and the waking dead clamber on. Onboard the train, a few fuzzy-eyed commuters mumble hellos to Tony Ferguson, 32, manager of a software licensing group for Silicon Graphics, who boarded the train one stop ahead, at the Fourth Street station downtown. Ferguson is remarkably upbeat this morning, despite the recent stock plunge at SGI (which he describes after some ill-advised jabbing as "not funny").

He points to co-workers on the car, those who nodded hello, and explains that half of his group lives in the city and commutes by car or train to SGI in Mountain View. Ferguson himself lives in Buena Vista Heights, near the Haight in San Francisco. At 6:45am, Ferguson leaves his house in the Heights, walks to Duboce Park, catches the Muni N Judah underground train, gets off at Powell Street downtown and then waits for the 30 or 45 bus to take him to the Fourth and Townsend Caltrain station. The 7:25 express train releases him and co-workers in Mountain View nearly an hour later, where a free shuttle provided by Caltrain, SGI and other companies whisks him to SGI headquarters. Ferguson finally sinks into his desk chair at approximately 8:40am. In the evening, the entire multimodal process is reversed.

Ferguson is a member of a burgeoning group of Silicon Valley employees who are willing to commit to careers in the valley, but not to the valley itself. Who seek the South Bay's corporate culture and six-figure salaries but San Francisco's style. These high-living, very tired commuters are willing to pay in huge chunks of their personal time to get what they want--in this case, the best of two worlds.

Rita Haskin, a spokeswoman for CalTrain, has been watching. And in the last five years, something she calls the "reverse commute" has increased dramatically. Traditionally--and certainly for most of this century--Bay Area workers have chosen to live in the southern suburbs and work in the north. San Francisco is still the No. 1 destination for train commuters in the morning. But since 1992, the number of commuters hopping aboard in the city to head south has nearly doubled. Palo Alto is the second most popular morning commute destination, with San Jose keeping a close third. Free shuttles from peninsula and South Bay train stations--provided in part by over 200 employers--have increased from seven in 1992 to 25 today.

On Fridays, the last car on the 5pm train from San Jose becomes a rolling happy hour, organized through email by an engineer at Intel, during which commuters heading north from the valley drink beers or margaritas, munch hors d'ouevres and mingle in the aisles all the way to Baghdad by the Bay.

Bay Area freeways are increasingly impacted by the same reverse-commute trend. According to Caltrans officials, morning traffic flowing southbound from San Francisco on Highways 101 and 280 has increased dramatically in the last few years. The evening commute on 101 northbound between Whipple and Third Avenue in San Mateo jumped from the 27th worst congested spot in the Bay Area to the ninth worst in just one year, from 1995 to 1996. Traffic increased similarly on 280 from 1993 to 1996, with a 13 percent increase in vehicles moving southbound out of San Francisco during the morning commute.

Los Gatos versus the Mission.

Where real culture grows.

Boomtown or Suburban Blight?

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO the American dream of owning a safe, suburban tract home with a yard? A two-car garage? Of getting away from city congestion, crime and poverty? That American dream in the valley now comes with the added bonus of a short commute to work as tech companies clamor for local workers. The median annual salary in Santa Clara County, with a 3 percent unemployment rate, is $49,564, compared to San Francisco County's $34,642. Compare averages and the difference is greater, $73,800 in the valley to San Francisco's $59,600, indicating even bigger rewards for the managerial and technical elite at the upper reaches of the pay scale.

Given its relative wealth and boomtown status (indeed, as the home base for some of the world's leading technology firms, the South Bay may be the biggest boomtown in the known universe), is Silicon Valley such a weak suburban oasis that workers are striving to get the hell away from it?

Well, yes.

When Jeff Willingham, 37, got a job with Bay Area-based Andersen Consulting, he could have chosen to live anywhere in the Bay Area. And although Willingham misses the greenery of his native Minnesota and faces a long commute into the valley while he fulfills a year-long consulting contract, he's chosen to live in the city. "My friends told me that if I lived on the peninsula, no one would come to visit me."

Tony Ferguson at SGI says his daily commute averages four to 4 1/2 hours. That's half a work day for most people, for which they are not paid. As a result, he's rarely both awake and at home during the work week. But for him, there's no other way. Ferguson says he lived in Palo Alto for a year while working at SGI in Mountain View, 10 minutes away. "I was dying in Palo Alto," he says. "I'm just not a suburbanite."

In a perfect world, he adds, SGI would relocate to San Francisco. In the meantime, Ferguson doesn't think he could find an equivalent job in the city. "That would pay comparably? That would be tough. The city just doesn't have as much technology. In the valley, you have companies on the cutting edge, and you feel like you can really make a difference where you work. You can be creative and contribute. It's like a campus at SGI. There's a lot of energy and enthusiasm."

While valley companies entice employees with stock options, gourmet cafeterias, free beverages, concierge services, swimming pools, break rooms, massage, yoga, oil changes and more, somehow the surrounding valley culture doesn't have what it takes to entice certain employees to stick around after hours. "I make all this money in the valley," Ferguson says, "and then go into the city to spend it."

The reverse commute is driven by former suburbanites like Ferguson who have fled to the city, but also by city people who've ventured south for jobs. Silicon Valley is booming so loudly, companies there now cast their nets across a wider geographical range, a larger pool of employees, including young urbanites who shudder at the thought of tract housing and chain stores. According to Dan Johnson, 29, a city resident and buyer for San Jose State University: "I can't get a job that pays me enough to work in the city. There are too many people too qualified there. You attach 50 miles of commute every day, and a lot of people drop out of the race." Though his commute is 4 1/2 hours each day, "no matter what," Johnson says, he'll take the city. "The rent in the valley is just as expensive, and the quality of life is way inferior."

Look at this trend as a tale of two cities: A lack of high-paying, career jobs in the city sends urbanites south, while a lack of culture, public transportation and village atmosphere in the South Bay sends software engineers north.

For some reverse commuters, who tend to put in long hours at work, a move away from the suburbs and close proximity to work is about putting distance between their jobs and their lives. When Ferguson worked and lived on the peninsula, "work was all I did," he recalls. "I'd stay in the office until 10 because it was easy. There was nothing else to do, and there's never any lack of work. Getting on the train enforces a certain amount of discipline, so I'm out of the office by five or six."

Many commuters echo this sentiment. Even time on the train or stuck in traffic in a car is a private rite of passage, a bit of treasured down time which clears their minds for home. And once they're home, work is, literally, miles and miles away.

Whatever their reasons for their two-city lifestyles, reverse commuters on CalTrain confess that they rarely hang in the valley. When asked where they've ever, say, gone for drinks or fun down south, they can't remember the names of any clubs or restaurants.

The Way From San Jose

OTHER COMMUTERS say they dislike the South Bay's car culture and the spread-out neighborhoods and miss the convenience of walking or taking a bus from home to the corner grocer, florist, thrift shop, cafe or Black Muslim bakery. Suburban malcontents bemoan a dearth of concentrated live music, entertainment, art and vibrance. Or they claim to be escaping what they perceive as a homogenous culture. "I wanted to be farther away from computer people," admits Kameron Hoang, 24, a software engineer at Intuit in Palo Alto who lives in the lower Haight, where he hangs out in bars playing chess on nights when isn't collapsed in bed after a long commute. With his feet kicked up on the train seat in front of him, Hoang exemplifies the hip-techie persona, dressed down for work in black Converse high tops, a shell necklace, swank haircut and Intel eyeglass band. "There are three kinds of people in Palo Alto: students, who I just got away from; computer people; and venture capitalists," he says.

Although San Jose boasts a much larger general population of Latinos, San Francisco's ethnic soup is indeed more spicy, with more Asians, Blacks, Samoans and Central Americans. All this in an area less than 4 percent the size of Santa Clara County, and with roughly half the valley's population.

But the new commuter urbanites prefer this dense, mad mix of people. They say it lends perspective. For them, life in the South Bay is like a fresh loaf of white bread: too soft, too warm, too much the same, too, er, white.

The north, these urbanites say, is the "real world," an equalizer. They draw joy from its diversity. "I can be sitting on a bus with a bum and someone in a suit who has just come from the financial district--and just for that moment, it doesn't matter," says Hoang.

Rose Kim, 38, works at Acuson, a peninsula-based ultrasound technology manufacturer. Her boyfriend's family lives in San Jose, so Kim, who lives in the Richmond District in San Francisco, says she gets down to the South Bay often. Still she wouldn't trade the city for the 'burbs. "In the South Bay, there's a lot of affluence, and I think people don't know what they have. You see what you have in San Francisco--and what you don't have. Some of my best friends there are waiters, busboys, directors. It's not so much what the South Bay is lacking, but what San Francisco offers."

What does San Francisco offer?

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, reverse commuters refer to San Francisco as a "world-class" city, and its South Bay equivalents as, well, not really cities at all.

Just the idea of San Francisco seems to be enough to draw some of them in, especially since many commuters don't even have time to take in the sights and enjoy the arts. "I don't really do much," confesses Johnson, "but I like the fact that I could if I wanted to." Others utilize San Francisco fully and have developed their own treasured communities by joining groups and classes, befriending people in bands or practicing their own art. "Everybody in San Francisco's got their medium," Johnson notes. "I do collage. You've gotta do something, because people in the city look down on you if you're just a regular worker."

"Commuting is just the price I pay to love the job I have and love the city I'm living in," says David Ansel, 32, deputy district attorney for Santa Clara County. Ansel's commute is a full two hours each direction, from his home in the upper Mission near Castro to downtown San Jose. "San Francisco is such a beautiful city, very tolerant and multicultural. And it's a walking city, with diverse street life. So you go out into your neighborhood, and you are immediately very much a part of that neighborhood, of that life."

Ferguson contends that between Silicon Valley and the city "there's no comparison. I walk out of my house in the city and immediately take in the neighborhood cafes. I can fill my day just watching people walk by--creative, independent, artistic people." On weekends, Ferguson stays up late at Cafe du Nord, Bruno's and Jelly's.

"San Jose," on the other hand, "is still trying to grow up," he says. "It's like a toddler that wants to be a city. It hasn't developed a grittiness and soul. It just feels like a large suburb to me."

San Jose's defenders--including Fil Maresca, former nightclub owner and past president of San Jose's Downtown Assocation, who now operates an event-production company out of his downtown San Jose, South First Area (SoFA) flat--struggle to compare San Jose's urban lifestyle to San Francisco's. Citing Adobe, the one major computer company downtown, Maresca points out, "If you worked for Adobe, you can live an urban life here. You could throw away your car." As a South Bay urban dweller, Maresca keeps his car in "storage." And the former San Francisco resident says he enjoys the neighborhood feel of the SoFA, riding his bike around, chatting it up with shop owners.

Still, his arguments on behalf of San Jose feel stretched and anemic, much like the city's downtown. Even Maresca acknowledges, "San Jose is growing slowly. I'm sticking around to see what I can help make it into. In San Francisco, people like me are a dime a dozen. Here, I can really make a difference. ... You have to be willing to smell the potential here. More companies need to move downtown. Hopefully, they'll realize that their 25-year-old engineers want an urban lifestyle."

In the meantime, those engineers will take a full-grown city over a fledging one. From his decade as a San Franciscan, Maresca understands that. "San Francisco is exciting. I lived there in my 20s, and I can't say that they're wrong."

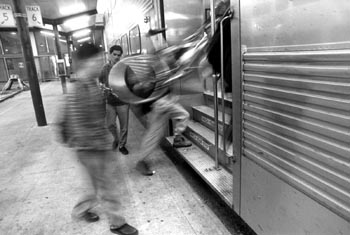

Hipper Than Thousands: Morning Caltrain commuters in San Francisco wait for their ride to the well-paying, perk-rich jobs in the burbs Silicon Valley, which they happily abandon at day's end.

Autorama

ALISA CARATOZZOLO grew up in the tony Saratoga-Los Gatos area. She now works in the South Bay, doing marketing at Stanford University Press. And although her commute is long, she says she'd never consider living south of Daly City. "I have 'issues' with the South Bay," she explains. "As a 24-year-old, I associate the South Bay with established families and suburban sprawl. You had to get on Stevens Creek Boulevard to do anything. Even to get to the grocery store, you had to get in a car."

This autoo-as-anathema theme is echoed by most reverse commuters. Though some drive huge and hypocritical distances to get to work, they'd rather not be in their cars in their own neighborhoods. "You have to drive everywhere down there," says Rose Kim at Acuson. "It's so suburban, and it's hard to find where the neighborhoods are. It sounds funny 'cause I spend so much time in the car, but I like the freedom of not being so car-dependent. ... In the city, I can take the bus. Even in my car, I can be by the ocean or downtown in 15 minutes."

Cost-Benefit Analysis

KAMERON HOANG says that before he moved to the city, he looked first in the valley for housing, but rental rates were too expensive. Today, the housing crunch in San Francisco is more like a strangle and has bounded beyond that of the valley. Rental associations and agencies in both San Francisco and Santa Clara counties report a 1 to 3 percent vacancy rate. The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Santa Clara County? Roughly $1,055. In San Francisco? $1,250.

"It's a pitiful market right now for renters," confirms Sheree Dodge of San Francisco's Roommate and Apartment Network. Still, workers from the valley come north seeking shelter. "The people who come to me who work in the valley are basically saying there's nothing to do down there. They want the social life here. And those people who work in Silicon Valley are the people who can afford to live here."

Refugees from suburbia escape a county with an exploding population and no housing to embrace another county with an exploding population and no housing. Both areas have surpassed all census estimates for population growth in this decade and are expected to continue to boom. Both counties have such high housing costs that a lack of disposable income is now threatening the sale of goods, and thus government income from taxes. At this rate, you wonder why anybody would choose to live in the Bay Area at all.

Reverse commuters pay dearly for their love of city life. At a nifty Web site called the Salary Calculator, punch in your annual salary in your "home" city and see what you're worth in any other mildly major city in the world. Say you made $40,000 in San Francisco and wanted to move to the valley--to San Jose, specifically. You'd only have to make $37,396 to maintain the same standard of living you enjoy now. Reverse the process, and reverse commuters who pull in 40 grand in the valley are losing approximately $2,785 a year attributable exclusively to where they've chosen to bed down at night. Makes you wonder.

San Francisco may be "world-class," but it's still costly, crowded and crime-ridden in comparison to the suburbs. On the other hand, money's not everything. If you wanted to live in Tuscaloosa, Ala., you'd only have to make $21,585 to maintain your current standard of living. If you wanted to live in Tuscaloosa, Ala. If it makes anyone feel any better, the same standard of living in Manhattan would cost you $65,347. So be grateful.

At Alumnae Resources, a job-placement service in San Francisco, Director of Counseling and Curriculum Mary Brennan reports that one major criterion for many of the work-seekers in her support groups is that they live in San Francisco. And preferably work here, too. "People really do want to be in this dynamic city." San Francisco's standing as the bay area job leader, however shifted between 1994 and 1995. In 1994, San Francisco looked like the stronger job economy, with an unemployment rate of 5.4 percent, compared to the South Bay's 6.2 percent. The following year however, Silicon Valley edged ahead, with its jobless rate dropping to an impressive 4.9 percent. Since that time, the south-favoring disparity has remained, culminating in Silicon Valley's remarkably low jobless rate of 3.3 percent for the first half of 1997. And another place San Francisco lacks dynamism is in its type of industry--primarily in banking, insurance and finance. This is one reason job-seekers give up and go south, at least from nine to five. "At many of the 'old-type' industries, in banks and in finance, there's still a real hierarchical corporate structure and stifling office atmosphere," Brennan explains. "People walk in and come back and tell me they just can't stand it."

S.F. Firms More Stodgy

THE REVERSE-COMMUTE story, as commuter Tony Ferguson puts it, "isn't so much San Francisco vs. the valley. It's technology vs. banking. Technology vs. law and insurance and all these very tight, conservative industries."

Rose Kim served as consultant to the banking industry before landing a job as director of information technology at Acuson in Mountain View. For Kim, the appeal of Silicon Valley is more than just money. "It's the concentration of creative people, of cutting-edge companies, of a work life that's more open and companies that demonstrate a genuine concern for most of their employees," she says. "The commute is crazy, I know, but when it comes right down to it, this [the valley] is a great place to have a career, and San Francisco is a great place to live."

The reverse commute may be made less crazy for Kim and others like her in the future if San Francisco--predicted to enjoy the largest job growth of all Bay Area cities in the next 15 years--catches up to high-tech corporate culture.

According to a report by the Association of Bay Area Governments projecting trends into 2015, the decentralization of high-tech is expected to continue and to contribute to the job boom generally in the Bay Area. If anyone can afford a place to live by then, San Francisco denizens who want the best jobs, and the best spot on the planet--in their minds--may just be able to have their Black Muslim bakery cakes and eat them too.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Robert Scheer

From the Nov. 20-26, 1997 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)