High-Wire Acts of Art

In his mobiles, Alexander Calder made engineering a playful pursuit

By Ann Elliott Sherman

WITH PERFECT TIMING for the holidays, the San Jose Museum of Art serves up a generous bounty of vision and wit created by a remarkably inventive and prolific artist. Flying Colors: The Innovation and Artistry of Alexander Calder unfolds with the magical grace of a present held together by a single red ribbon.

Throughout, the installation demonstrates uncommon simpatico with Calder's approach to color, and the curatorial notes share his knack for being both accessibly direct and sophisticated. Guest curator Helen Ferrulli helps put Calder's multifaceted creativity in the context of his personal experiences, engineering training and zest for life--as well as his era's imaginative fixation on technical advancement.

Fascinating tidbits (one gem: the mental image of Albert Einstein issuing a Homerian "Doh!" after studying Calder's A Universe for 40 minutes) and the unpretentious quotes lettered on the walls convey the always refreshing message that intelligence and joyful enthusiasm are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

By now, mobiles are an art form most of us have literally grown up with, thanks to their invention by Calder in the '30s. Kids and adults alike will be drawn to the striking blend of clarity and wonder in mobiles like Roxbury Flurry, its whirl of white discs beautifully offset by a vibrant blue backdrop.

A buttercup-yellow wall displays creatively whimsical proof that Calder did "think best in wire": 3-D doodles and sketches, including a fish toilet-paper holder, a valentine and a portrait of Edgar Varèse. And the perfect foil for a series of mobiles primarily executed in black and white--"the most disparate colors," as Calder put it--is a red wall, the color "most opposed to these" and the artist's favorite. Judiciously sprinkled throughout are Calder's vibrant prints, paintings and tapestries.

After graduating from Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey--where, prophetically enough, he got unprecedented high marks in descriptive geometry--Calder worked as a kind of engineering roustabout while attending the Art Student's League. His first artist's gig was drawing athletes for The National Police Gazette, which later sent him to cover "the greatest show on earth," the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Exuberant line drawings and gouaches show Calder's enthusiasm for the task. Inspired, Calder began to fashion his own miniature, manually animated one-ring circus out of wire, fabric and bric-a-brac.

An engaging short video of Calder's Circus shows the artist cranking and pulling his performers into action. A staged aerial accident and emergency response suggest possible inspiration for the relationship between former Saturday Night Live characters Mr. Bill and Mr. Hand. The gruff French narration of Calder's ringmaster can't obscure the artist's good humor and inventive means for creating comic movement that translates into laughter reverberating throughout the museum.

CALDER'S MINICIRCUS performances in Paris for the artistic avant-garde were his passport into that club. The exhibition's inclusion of toys, jewelry and gifts that Calder gave to family members provides a ready understanding that this was a particularly fitting debut for a guy who started out crafting playthings as a child and never stopped.

Soon after came Calder's appropriation of Piet Mondrian's primary-color abstractions into the realm of three-dimensional art; Marcel Duchamp's coining of the term "mobiles" for Calder's moving, suspended sculptures; and Jean Arp's corresponding jest of "stabiles" for the dynamic grounded works represented here by pieces like The Arches.

Just as Calder rescues our image of the artist as tortured soul, so might he liberate engineers from the stereotype of socially backward nerds. He was a bon vivant who sometimes made the equivalent of balloon animals out of wire champagne cages at parties, and his expansive curiosity, natural optimism and spontaneity allowed him to develop his art in several different directions simultaneously.

Calder's complementary gifts for mechanical engineering and imaginative play made him uniquely suited to emancipate sculpture from the stolid pedestal and create a dynamic, sometimes capricious interaction with its environment. Not only did Calder intuit that an art in motion more accurately reflected the postindustrial world, he grasped that in such spatial and kinetic dynamics we can behold the universe.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

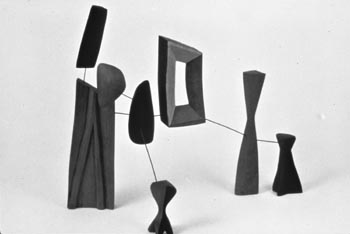

Going Mobile: Alexander Calder's 1943 wood-and-wire construction 'Constellation With Quadrilateral' shows off the artist's love for dynamic whimsy.

Flying Colors: The Innovation and Artistry of Alexander Calder runs through Feb. 1, 1998, at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. Market St. (408/294-2787). The corresponding interactive art studio Balancing Act: Playing With Alexander Calder runs through April 15, 1998, at Children's Discovery Museum, 180 Woz Way, San Jose (408/298-5437). A series of Sunday kids' workshops at CDM taught by SJMA Art School faculty runs through Jan. 11, 1998. (271-6875)

From the Nov. 26-Dec. 3, 1997 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)