![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

On the personal growth frontier: Is spoon bending the firewalking of the new millennium?

By

DEFORMED SPOONS and forks lie strewn across a wooden table at the side of the auditorium in the O'Connor Hospital Medical Office Building when I walk in. The utensils are twisted into every imaginable configuration: spoons with their handles twirled into spirals and bowls buckled over, forks with their tines bent down to the handle or wrapped around each other like strands of ivy. There are hundreds of them--some stainless steel and some silver-plated. The mass of mangled cutlery looks like a reject pile from some perverted science experiment.

Jack Houck, a slight, gray-haired astronautical engineer who spent 42 years at Boeing, stands by the stage, talking to a reporter from TechTV. Houck's 363rd Psychokinesis (PK) Metal Bending Party is about to begin.

Houck unveils a milk crate filled with more than 1,000 sacrificial spoons and forks that participants will pick through and attempt to bend. The distorted utensils on the table are remnants from previous parties.

By using collective energy to create a "peak emotional event" that makes the metal soften, psychometallurgists will be able to twist silverware into bizarre sculptures with a minimum of physical effort. According to Houck, using psychokinesis (mind over matter), the human mind can somehow dump energy into the natural dislocations of the metal molecules inside the spoon. This energy can soften the spoon, as if it had been heated, allowing you to bend it in ways you can't do with simple physical force.

Houck began hosting these unusual parties in 1982, and this gathering is the latest of many he's hosted in the San Jose area. The event is a fundraiser for the Foundation for Mind-Being Research (FMBR), a local multidisciplinary organization of scientists, doctors, engineers and alternative healers. The foundation's mission is to garner wider recognition for the field of consciousness studies as a bona fide science.

Established in 1980, FMBR explores "integrated models of consciousness with emphasis on the nature, power and role of thought and the relationship of one's worldview to the process of perception" through lectures, workshops, reports and research projects.

The group's website (www.fmbr.org) contains a wealth of intriguing editorials and papers on a myriad of subjects: DNA, quantum entanglement, the science of the absolute, the importance of imperfection, interdimensional communication and how boredom is the antithesis of the spiritual life. The foundation has no official phone number, just an email address and a post office box in Los Altos.

Ellen DiNucci, who teaches the energy-healing method known as Reiki and who serves as the foundation's vice president, welcomes me to the party, as does William C. Gough, a retired electrical engineer, who founded FMBR 23 years ago.

People of all ages begin to file in, some armed with their own forks and spoons. Houck says he doesn't use knives, because sometimes they break apart and cut people, one of those little-known dangers of psychokinesis that you don't learn about at the movies.

While gazing at all the kinked-up silverware from previous events, I contemplate: A spoon-bending party? This is just sooooooo 1970s. Is Uri Geller--the psychic who popularized spoon bending 30 years ago--going to make a guest appearance? Is professional skeptic James Randi waiting to waltz in with a cape and debunk the whole thing? Will people jump up and down with giddy euphoria after twirling spoons into complex helixes?

Well, one out of three isn't bad, I guess.

Twist and Shout

By way of encouragement, Houck shows off a few half-inch-thick zinc-coated steel rods he claims a 6-year-old kid bent at a previous party. Not a Superman bend, but just enough of one so that the rod no longer rolls on a flat surface.

Before we begin in earnest, a female member of FMBR tells Houck that she'll "sense" the energy level of the room, in case there's any negative energy floating around.

"If there's someone with negative energy, I'll levitate him," Houck says facetiously.

Slender and soft-spoken, Houck believes that once a person learns how to use mind over matter to bend spoons, then achieving other goals and doing important things in life become much easier.

"It's not about me being high-powered," he explains. "It's about me teaching people how to do this. The more exciting we make this event, the better it works. When I ask you to shout and jump up and down and scream, I mean it."

In a dry, almost hypnotizing tone, Houck starts by detailing his background and the 20-year history of his PK parties. His wireless microphone goes out several times. Some things are beyond even Houck's mind control.

Finally, Houck picks up the milk crate and dumps about 1,000 perfectly good stainless-steel spoons and forks all over the floor. Guests are instructed to grab a handful of silverware in order to ascertain which ones will be suitable for manipulation.

To do this, each person picks up a "dowser," a pendulum-type device that looks like just a colored bead on a piece of white string. The next step is to ask the pendulum which direction it will swing when answering "yes" or "no" to the holder's questions.

"Show me yes," people ask the piece of string with a colored bead. Once that's determined, they hold the pendulum over individual spoons and forks and ask out loud, "Will you bend for me?"

Now, visualize the scene here: an entire room filled with people dangling pendulums over their spoons and asking, "Will you bend for me?" It feels like an episode of The Twilight Zone. I keep waiting for Rod Serling to chime in with the epilogue, but he never does.

Once we divine five utensils that produced a positive response from the pendulum, we move our chairs into a circle, two rows deep, and sit down.

"If you don't sit in the circle itself, you won't be able to bend the metal," Houck explains. He also explains that saying to ourselves, "I can't bend the spoon," would create a mental block. So we are forbidden from saying the word "can't."

We each stand up and hold our spoon out in front of us, clutching both ends with the thumbs and forefingers of each hand. Houck instructs us to concentrate our thoughts on a point of energy in the air above our heads and focus on it. Then he tells us to follow the point, grab it, bring it down through our head, neck, shoulder, arm, hand, and put it into the silverware where we want it to bend.

At the count of three, everyone begins to yell, "Bend! Bend! Bend!" several times as we hold the spoons. Of the 80 people in the circle, a few of us are immediately able to twist our spoons into spiral shapes (see photo).

One woman jumps up and shouts that she has bent her spoon, waving it in the air with orgiastic glee, as if she has just been healed at a Pentecostal tent revival meeting. For others, the exultation comes gradually.

I do not feel any particular "energy" in the room, but somehow, I just know that I'll be able to do this. And the metal of my chosen spoon honestly feels as if it has softened up and became pliable for a few seconds.

It takes no brute force to spin the thing around into a spiral with my hands. After a few seconds, the spoon feels as though it has hardened back up again. I can no longer twist it with ease.

I repeat the process of focusing on the "energy" and attempting to "redirect it" into the spoon and achieve similar results three more times. One try, I twist a spoon around and around for several turns. With another spoon, I can only twist it once.

The person next to me just stands there, staring at his spoon; he can't get it to bend at all. Over time, about 50 percent of the participants are able to bend, twist and mangle the silverware. The whole event seems both blissful and creepy at the same time--like a cross between a faith-healing session and a scene from Rosemary's Baby.

Those who bend spoons or forks joyously celebrate, and a giddy euphoria settles in.

My reaction, however, is that of absolute indifference. I hold my four bent spoons in the palms of my hands, look down at them and think, "All right, I bent spoons. So what?"

Focused Inattention

Former stage magician and author James Randi is the grand old man of professional skeptics. He's spent the last three decades demystifying and blowing the lid off so-called paranormal and pseudoscientific phenomena. On April 1, 1998, his foundation (www.randi.org) launched a $1 million offer to anyone who could show, under "proper observing conditions," evidence of any paranormal, supernatural or occult power or event. The prize has yet to be claimed.

Randi says--and has said for 30 years--that spoon bending is just a parlor trick, that it has nothing whatsoever to do with "psychic" abilities. If you believe otherwise, you're being hornswoggled.

What he's talking about is when someone like Uri Geller does it onstage or in front of the camera. But when it comes to Houck's PK Metal Bending Parties, Randi won't hesitate to go after them either.

Ranting over the phone from his Fort Lauderdale, Fla., office, Randi begins, "There are a lot of these guys out there. What they do is they tell you to put pressure on the spoon but not enough to bend it. Now, what if I told you to take a wine glass, rap it on the edge of the table, but not hard enough to break it? How do you do that? How do put enough pressure on the spoon but not enough to bend it? Then concentrate on it, and it will bend.

"You don't know how much pressure it takes to bend the spoon or to break this wine glass. That's the point. You can tap it on the table a number of times, and it won't break, then when you concentrate on it, it will break. But at the point where it does break, was it because you added something to it or because you rapped it a little harder or at a slightly different angle?"

Boiling with skepticism, Randi continues: "He's telling you to put pressure on the thing. He doesn't tell you to bend it with your mind; he tells you to put pressure on it but not enough to bend it with your hands--and then add energy to it from your mind. How do you know where that energy is coming from? You don't know."

Well, when bending my four spoons, I barely used any physical force, although it's hard to tell, since it all happened so fast. Maybe I was tricked into thinking I didn't use brute force when I really did. But it hardly seems possible that one can create as fluid a bend as I did with sheer muscle power. I don't have any sheer muscle power, for crying out loud.

After bending a spoon, you're left with a bizarre feeling--almost as if you had just done something you know is impossible, but it can't be a trick, because you just did it. No sleight of hand, no rabbits pulled out of hats, no nothing. But since it's supposed to be impossible, you're not supposed to believe it.

FMBR's president, Sylver Quevedo, M.D., declares in a paper on the foundation's website that "this is the same criticism you hear from allopathic doctors about homeopathy studies that have a positive result. Even if the data are correct, i.e., true, [they] still don't believe it, because it is impossible. It violates a materialist principle that is part of their belief system. Materialism has become more fundamental than the principle of empiricism--or they would let the data speak for themselves."

But Randi dismisses all of this. "Anyone can bend a spoon. It's not too difficult," he tells me. "I can stick my finger in my eye, and that's not too difficult. I don't do it very often, but I can do it. I bend a couple of forks a week because people order them through our website. I simply twist them around. It's not difficult at all. Of course, it depends on the fork or the spoon. Some you can't bend at all. People just don't do this with spoons, you see. How much pressure does it take to break a wine glass? I don't know, because I don't go around breaking wine glasses. And I don't go around bending and destroying spoons and forks and that sort of thing, so I don't know."

Jurassic Park author Michael Crichton once published a nonfiction book, Travels, in which he recounted globe-trotting endeavors, including a visit to one of Houck's PK Parties in 1985:

The one thing I noticed is that spoon bending seemed to require a focused inattention. You had to try to get it to bend, and then you had to forget about it. Maybe talk to someone else while you rubbed the spoon. Or look around the room. Or change your attention. That's when it was likely to bend. This inattention took learning, but you could easily do it.

Crichton's right. It's almost as if you have to not think about it in order to do it. The only difference, however, is that I didn't rub the spoon at all. I just held one tip with my thumb and forefinger and the other tip with my other thumb and forefinger.

I held the spoon for maybe 30 seconds beforehand, and the spoon honestly felt as if it had become malleable somewhat. The "focused inattention" settled in, and exactly as Houck had explained to the group, as soon as I "let go" of the situation, I was able to twist the spoon around and around.

If it's all indeed a trick, I definitely don't know what the trick is. I doubt that Houck went through the trouble of doctoring a thousand pieces of silverware before he showed up.

Was I hypnotized? Was it The Twilight Zone? Did Rod Serling enter the picture after all?

I guess I'll never know. But I do have some pretty twisted artifacts to show off.

Bend and Heal

"Experience is the foundation of physics and the foundation of our understanding of nature," FMBR founder Gough says over the phone from his Los Altos home. "Our experiences are limited, and we've taken a lot of belief systems in. And when you bend spoons or do something like that, it can change your belief system. And people come have back to me years later, saying [something like], 'I've got cancer, and I remembered that I could bend spoons, and that gave me the strength to go ahead and fight this disease.'"

Which is exactly what Houck explained in his preparty talk--that once you realize you can bend a spoon, other goals and achievements might come much easier down the road.

"We have a belief block in our systems right now," Gough continues. "A lot of people believe that their mind is kind of separate and doesn't really affect the physical world. That the power behind those thoughts and emotions is not that powerful. But they are much more powerful than we normally believe. And [spoon bending] helps convince you."

On Crichton's website, he responds to a question from a fan about whether or not he still believes in the spiritual experiences he wrote about in Travels.

Of all the things I wrote about, spoon bending seems to stick in the rationalist throat. It just bugs people. I don't know why it occurs. I have no explanation. I can't describe it any better than I did in the book. But I have no doubt that it occurs. More than seeing adults bend spoons (they might be using brute force to do it, although if you believe that I suggest you try, with your bare hands, to bend a decent-weight spoon from the tip of the bowl back to the handle. I think you'd need a vise.) But to see a little kid of 8 or 10 running around with a thick bar of aluminum that he has bent--not a lot, but enough so that if you roll it on a table, it doesn't roll flat--is to realize that whatever is going on, it's not brute force. I think that spoon bending is not "psychic" or bugga-bugga. It's something pretty normal, but we don't understand it. So we deny its existence.

I'm with Crichton. Call it a cop-out if you must, but I have no idea how spoon bending works. But it obviously does work. Maybe it does indeed have something to do with the subconscious and/or some undocumented combination of biochemical, electrical and magnetic something-or-other that changes the arrangements of molecules in the spoon.

But this does not necessarily mean it's a "supernatural" phenomenon of any sort. There's definitely a physical reason why it happens. What that reason is, I don't know. As others have said before me, I will remain agnostic as to the psychics.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

Twisted Experience

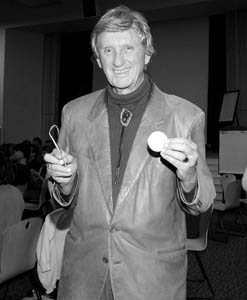

Master Manipulator: William Gough buckled the bowl of a silver-plated spoon, earning him a Certified Warm Former badge, an award for those who graduate from "kindergarten" to "high school" bending.

FMBR's next meeting takes place Friday, Nov. 28, at 8pm in the O'Connor Hospital Medical Office Building, 2101 Forest Ave., San Jose. Dr. Rollin McCraty's lecture is titled: "Intuitively Perceiving the Future: The Latest Scientific Research."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the November 27-December 3, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.