Sculpture has traditionally been a male-dominated art form until the emergence of female sculptors in the 19th century. One such artist was Edmonia Lewis, who not only carved a name for herself in the medium as a woman, but also broke the color barrier.

Lewis was the most famous female sculptor of color in America. Done in neo-classical style, her sculptures were inspired by Civil War heroes, abolitionists, biblical characters and mythical creatures, as well as her Black-Indigenous heritage. The Cantor Arts Center’s new exhibit, “Edmonia Lewis: Indelible Impressions,” which runs Sept. 17 to Jan. 4, explores both her life and work and her connection to the Bay Area.

“In the course of my research, I learned that three of her sculptures were on exhibition at the San Jose Public Library,” says curator and Stanford University professor Jennifer DeVere Brody, who’s writing a forthcoming biography on Lewis. “And while they’re accessible to the public, they are behind a wall and not in a museum context. So I had the idea to bring them to the Cantor and to the larger public.”

Lewis was likely born in 1844 near Albany, N.Y., of mixed African, Haitian and Ojibwe descent. She was orphaned at a young age and raised Catholic; her half brother, Samuel, lived for a time in San Francisco. She attended Oberlin College in Ohio—one of the few colleges that admitted female students—but was forced to leave before graduating due to accusations of stealing and poisoning classmates, which were thought to have been racially motivated.

Lewis opened a studio in Boston, where she created portrait medallions of well-known abolitionists. After moving around Europe, she set up another studio in Rome that was home to a group of female expatriates, namely Harriet Hosmer, the most famous female sculptor, and Emma Stebbins, who designed the central sculpture in Central Park’s Bethesda Fountain.

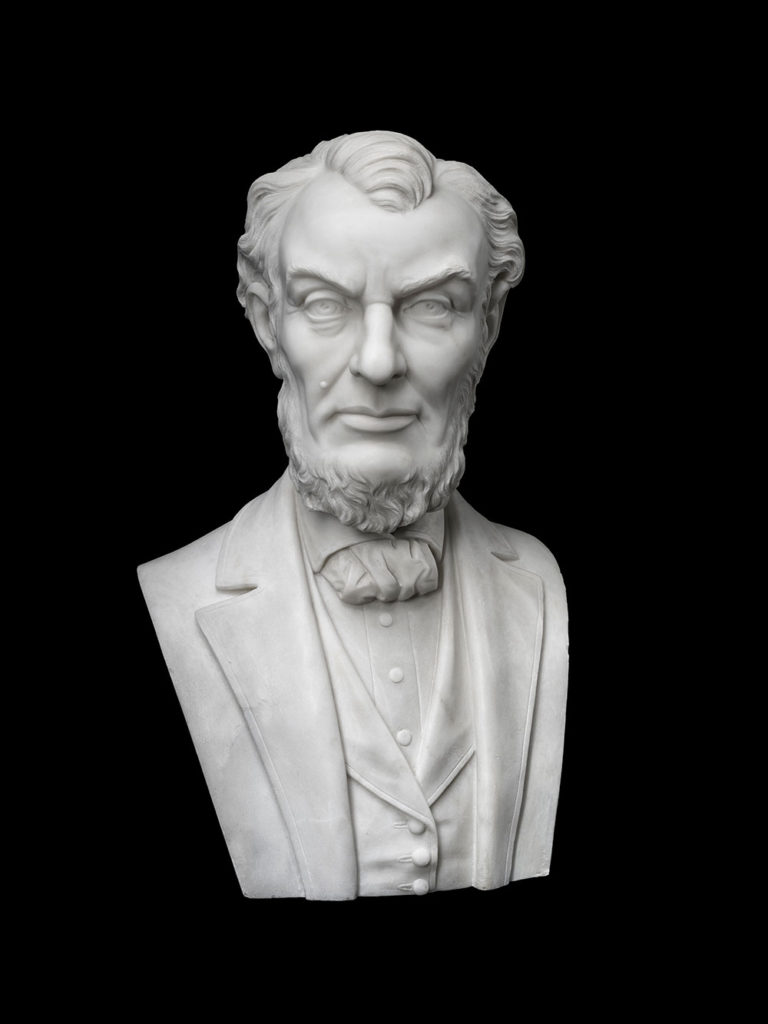

Frederick Douglass visited her there. Ulysses S. Grant commissioned a bust of himself. Lewis also sculpted a bust of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose poem The Song of Hiawatha inspired her sculpture, Old Arrow Maker.

In 1876, she displayed her most famous sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra, at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The statue, which took ten years to complete and weighs more than 3,000 pounds, depicts Cleopatra at the moment of her death. It went missing for nearly a century, having traveled around various locations, including a saloon, golf course and a mall. The sculpture currently resides in the Smithsonian American Art Museum along with several other Lewis works.

Lewis exhibited in San Francisco in 1872 and in San Jose in 1873; an article published in a local Black newspaper described her art as having “indelible impressions.” A fundraiser was organized to purchase her bust of Abraham Lincoln as a gift to the San Jose Public Library. Sarah Knox-Goodrich, a women’s suffrage activist in San Jose, bought Awake and Asleep, Lewis’ companion sculptures of two small children. All three are housed inside the library’s California Room. The Cantor exhibit, which also features historical text, articles, photographs and video, will be the first time the three sculptures have been shown together outside the library in 30 years.

“The sculptures are about sleep and peacefulness,” says Brody. “These images of sentimental innocence were very popular in that period.They were made to sit in homes, on a table. They talk about the cycles of life. And they were cut from a block of stone, so you have to remember how much was involved in chiseling the exquisite details.”

There has been a resurgence in Lewis’ art the last couple of years. She died in 1907 in London in an unmarked grave, but her grave was restored thanks to a GoFundMe. There was a play and opera made about her life. In 2017, Google announced a Google Doodle in Lewis’ honor. In 2022, the U.S. Postal Service celebrated Lewis with a Black Heritage stamp. And that same year, Oberlin College issued her a posthumous diploma.

“There was a historic precedent for art and culture in the Bay Area during the Gilded Age,” Brody says. “One of the key figures to help foment that was this American sculptor who produced works for this burgeoning culture. She was a sculptor from the U.S. who had made a name for herself globally, and she brought that cachet back to the Bay Area.”

Edmonia Lewis: Indelible Impressions runs through Jan. 4, 2026, at the Cantor Arts Center, 328 Lomita Dr., Stanford. museum.stanford.edu