The following is an excerpt from Mike Huguenor’s first book, Elvis is Dead, I’m Still Alive, which will be published May 19, 2026 by Clash Books. Using material from more than a hundred hours of interviews with musicians, producers, booking agents, label owners, writers, fans, employees, volunteers, friends and family, Huguenor tells the story of Asian Man Records. Preorders for the book can be placed at clashbooks.com.

The way Tobin Mori sees it, some things really do happen for a reason.

“It’s funny,” he says, “in life, these events, you look back and go, ‘oh that’s what that was for. It was to lead to this.’”

For Mori, the pivotal event in life was joining his third band, San Jose folk-rock group the Dizzy Suns.

It was the mid-1990s, and he had been working for a Palo Alto tech company. The entire peninsula had become filled with tech companies jammed into soulless office parks lit from above by fluorescents. Eventually, their gravitational pull drew him in.

But Mori didn’t want to work in an office, or log hours at a technology company. He wanted to play music. He was a guitarist, had been since he was 13. In high school, he wanted nothing more than to play in a band. Yet, by his mid-20s, he still hadn’t had much luck finding musical peers.

Dizzy Suns didn’t last long, but, in a way, that was perfect. Soon after, Mori was reading Metro when he saw an advertisement that called out to him. It was two musicians looking to start a band: a singer and a drummer. “Which is like this perfect match for me, a guitar player with a bass player who I really like,” Mori says.

***

Anyone who lives in the South Bay Area knows the Pruneyard. Home to a movie theater, bookstore and (until recently) a bridal/quinceañera studio, host of drag queen bingo, purveyor of various comfort foods, teenage hang-out and meeting place of poets, smokers and first dates, the Pruneyard serves many functions.

On that day in 1996, it also served as a testing ground for two very circumspect Bay Area musicians.

Elizabeth Yi sat in the passenger seat, listening as Tobin Mori played her various tapes he had made over the years. It was enough of a spark to get them into a practice space together.

“I heard her and was like, ‘Oh man, she’s got an awesome voice,’” Mori remembers.

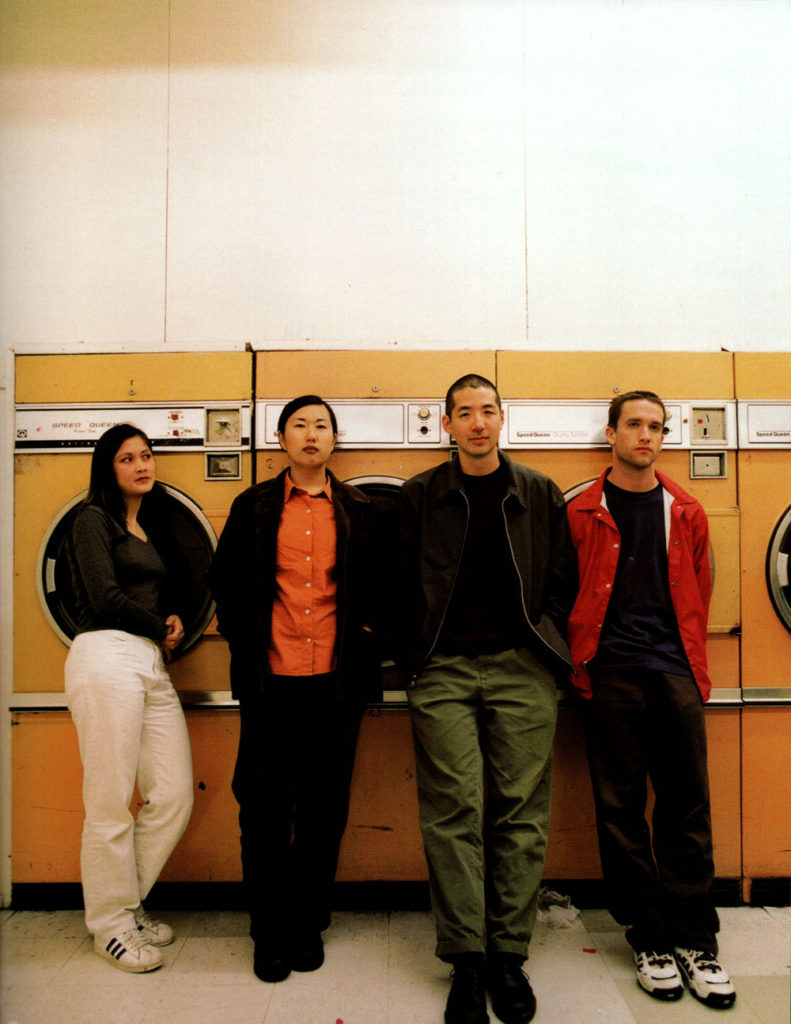

Korea Girl’s original line-up consisted of Elizabeth Yi, Tobin Mori, Summer Farnese and Mark Duarte. Though they are too often overlooked in the discussion of ’90s indie rock (the band rarely escaped the Bay Area), they were the first true indie rock band signed to Asian Man.

Mori had a habit of riding the line between indie and alt-rock. Yi, meanwhile, came to the band from a totally different perspective.

“Liz really wasn’t like an indie rock person, she’s just extremely honest,” Mori says. “In a good way. She had a great sensibility. It comes through in her songs.”

For example, the song “Under the Sun.” When Korea Girl were in their early stages, Yi had recently parted with Christianity after years of intense devotion. “Under the Sun” appears to catalog her challenges with faith, its chords funneling downward towards an E minor as she describes how she “searched in god and man, found everlasting pain, nothing new, nothing gained, the same, the same.”

Nowhere was her honesty more apparent than on the band’s de facto single, “Reunion.” Jangly and mid-tempo, it describes Yi’s scathing reaction to an invitation to her high school reunion.

“Why would I spend more time with people that I hate, couldn’t wait to leave behind?” she sings in the song’s chorus.

Her tough, sometimes bitter perspectives gave the band a scrappy duality. It was a quality they embraced with their logo: a smiling cartoon schoolgirl, blowing smoke off the muzzle of a revolver. Korea Girl was cute, but not to be fucked with.

***

Korea Girl self-recorded at the Practice Place in San Jose, seizing the odd off-hours when they were least likely to be interrupted by the blastbeats of drummers from neighboring rooms.

Using the Tascam four-track his father had bought him in high school, Mori tracked a demo tape of Korea Girl’s first four songs over a weekend in March of 1996. They sent them out to local journalists, radio stations and promoters. Then, they decided to start working on a full-length.

He scraped up a little cash and bought a nicer Tascam, the DA-38. It recorded eight tracks of digital audio onto Hi-8 video cassettes and offered robust sonics. But with only eight tracks, four mics and little other gear (plus the fact that Mori was not a trained producer), the band’s recordings were destined to be lo-fi. For vocals, they decamped to the half-basement beneath Mori’s rented house, “this frightening little pit” about four feet wide.

“At the time I was listening to Pavement’s Slanted and Enchanted, which is like a totally lo-fi record,” he says. “That was like my model. I was like, ‘If I can get it to sound as good as that or at least close, I’ll be fine.’”

They’d also drawn the attention of local music journalist Todd Inoue, who covered their performances in Metro. He told Mike Park about the band. In a rare move, Park decided to offer them an album without having ever seen them live.

Korea Girl wasn’t actively in the punk scene, but band members were still well aware of Asian Man.They earned enough college radio airplay, local interest and general buzz for Asian Man to offer a second album.

“It was like this golden opportunity, right?” Mori says. “Like, how many times do you get offered to have a record released by somebody?”

But there never was a second Korea Girl album.

They gave themselves a few months to write songs for the new album. But when those months were up, there were no new songs. Three months passed. Then six. Though he didn’t understand it, it seemed that the initial spark, that connection he had found with Yi back in his car in the Pruneyard parking lot, had gone out.

***

Maybe the world really was stretching at the time. Everything seemed to be in transition. Information networks were in flux and the world braced for Y2K. Matthew Shepard was killed for being queer, and students at Columbine were killed just for attending school (a traumatic event that has not stopped repeating since). The music industry, too, was in the middle of a seismic shift, the direct consequence of Napster sending the industry into a panic that would eventually result in the creation of Spotify and the rise of streaming.

During one of her earliest conversations with Mike Park’s father, Asian Man Records label manager Miya Osaki recalls he described to her something about the near future that she found difficult to understand. It was then 1997. The Parks, always ahead of the curve, had dial-up internet in the household. Only Shin Park, the microbiologist, seemed to really understand its potential.

“One day, he was like, ‘Miya, people are going to send you mail and it’s going to be on this computer,’” Osaki remembers.

“She gave him a skeptical look. At the time, the label thrived off mail order—physical envelopes stuffed with cash, sent in exchange for physical records. Osaki scoffed at the notion of a fake letter inside of a computer.

“I clearly remember being like, ‘Mr. Park, you don’t know. Why would anybody want to do that?’—and it was email!” she says today.

***

After the demise of Korea Girl, Mori relocated to the Sunset, a place that naturally breeds melancholy out in the eternal grey of San Francisco’s west end. It was overcast when he got up for work in the morning and overcast when he finished his lengthy commute home from the peninsula.

As he had with Korea Girl, Mori self-recorded his new band, Ee—this time with better microphones. They tracked the album in his apartment, where he was free to spend hours adding layer upon layer of overdubbed guitar.

Ee toured only once, but they made it count. They bought a van they dubbed “the Church Van” (white and long) and proceeded to play 18 shows in 21 days. They tackled the long drives in shifts. Four hours at a time, then rotate.

“One of the worst times we were driving for like 18 hours. We had a show in Brooklyn and we had to be in Chicago the next day,” Mori remembers.

By now, Ee also featured indie rock luminary Sooyoung Park, of Seam, and had a booking agent helping them. Sometimes, audience members were blown away to see Sooyoung play live. Sometimes, audience members were just as excited about bassist Che Chou, who they knew from his day job writing for Electronic Gaming Monthly.

“And these are Asian people coming up to us, which is, for me, kind of cool,” says Peter Nguyen, Ee’s second drummer.

Growing up in Ft. Collins, CO, Nguyen says it wasn’t until he saw Skankin’ Pickle come through town on tour that he actually saw another Asian American musician in person.

“It might seem small, but you do influence a lot of folks,” he says, of life touring as a musician. “There wasn’t a lot of representation for Asian American bands.”

Still, outside of tours like Plea for Peace, Ee’s shows remained modest. Some nights there were 50 people in attendance. Others, there were three. In Tucson, they had difficulty finding a place to spend the night, so half the group slept on the roof of the van.

In 2002, Metro Silicon Valley published a brief tour diary written by Mori, describing Ee’s trip to New York to play CMJ Music Marathon, the festival once thrown annually by College Music Journal. Mori opens the diary with an enthusiastic tone:

“Bands of all genres flock to the conference with hopes of ‘making it big’ or ‘bigger.’ For Sooyoung, Che, Pete and myself, CMJ possesses a mythic quality, like a rainbow at whose end stands greater fame or sales. We were fortunate enough to get a slot this year for our booking agent’s showcase.”

On its face, his assessment was accurate. In the early 2000s, CMJ had a lot of power. Following the meteoric rise of Arcade Fire, the band’s singer attributed their success not to the glowing 10/10 review the band received from Pitchfork, but to The New York Times covering their performance at CMJ. The 2002 festival included Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Gogol Bordello, My Morning Jacket, OK Go, Bright Eyes, Rilo Kiley and the Chemical Brothers. Tucked in alongside those, it also included many smaller bands like Ee, all of them hopeful of receiving even a small fraction of the attention of the larger names.

In Ee’s case, that did not happen.

“In the end,” Mori concludes his tour journal, “our trip to CMJ didn’t blow up our status; it was not very different from our other out-of-town tour dates.”

Arguably, it was very different in one sense: it came at a huge cost to the band. As a flyout date whose payment largely consisted of exposure, it cost the band much more money to play than it made them.

For his part, Mike Park has always been skeptical of industry fests like CMJ and South by Southwest, describing them as a “waste of money” and cautioning bands to play for their fans instead of label representatives.

“It’s the industry’s excuse to party on the company’s dime as a tax write-off and to show everybody, ‘look at us. Look at our industry,’” he says.

CMJ closed in 2017. Not long after their trip to New York, Ee began to fade away. Members left the Bay Area. Today, Pete Nguyen doesn’t even remember the band’s final show.

In Ee, Tobin Mori’s musical path stretched further than ever before, taking him beyond the four track and into the studio, under the wing of a booking agency and across the highways of America.

“It’s like therapeutic,” Peter Nguyen says. “That was the first time I drove across the country. You drive and zone out, look at the road and beautiful America. Fun, exciting, on edge. An adventure. Four Asian guys driving across the country to play music.”

Elizabeth Yi declined to be interviewed. She remains one of the greatest frontwomen in the label’s history.

***

One day Bob Vielma, bass player in my band, Shinobu, told me he had spoken with Mike Park and that Asian Man was interested in releasing a 7-inch of ours.

Like many of the previous bands on the label, we were a group of kids fresh out of high school, more interested in playing music and touring than in much anything else. Bob and I had gone to Lincoln High School together, a performance art magnet in San Jose. He was a year ahead of me, but our friend groups collided in my sophomore year due to a shared love of music. For a short time, I played guitar with his rap crew, the Rap$callionz. They didn’t seem to mind that I couldn’t play very well yet.

By the end of high school, I’d been in a few punk bands and wanted to start something a little softer. That ended up being Shinobu. From one of the punk bands I’d played with, I met a drummer, Jon Fu, and we began working on songs in his parents’ garage. Bob didn’t yet play any stringed instruments, but he was a trombonist and had taught himself piano. I figured he’d be a natural on bass—and he was. After a few practices as a three-piece, we added Jon’s friend Vince Tran on guitar. When Vince told us he didn’t want to tour, we swapped him out for Matt Keegan, whom I had known since elementary school.

Like Korea Girl, Shinobu self-recorded in our practice space, a small room in a converted warehouse in an industrial part of town by the airport. And, like Korea Girl, half of our recording time was spent waiting for the drummer next door to stop playing blastbeats long enough for us to get a clean take.

I had been inspired by the Weakerthans and early Death Cab for Cutie, non-punk bands that applied heavy restraint to get an emotional sound. Then, we had all gotten very into one of the least restrained bands imaginable, the Ging Nang Boyz.

Later, when Bob and Jon both moved to Japan to teach English, Shinobu toured with Bomb the Music Industry!, with Jeff Rosenstock and John DeDominici filling in on bass and drums, respectively. Worstward, Ho! did not do well on Asian Man. The few reviewers who heard it did not enjoy it. Not even Punknews. They wrote: “This album is not what I expected. The first track is just some guitar noise leading into the second track, which is abrasive at best.” The album version, Punknews said, was “slower, adding 17 seconds to the running time, and it’s all the worse for it.”

Shinobu continued releasing independent albums, and through friends’ labels like Quote Unquote Records and Lauren Records. Our time on Asian Man ended after Worstward, Ho! Now, all Asian Man’s files on the band sit inside a filing cabinet, in a manila envelope marked “Closed.”

Neither Korea Girl nor Ee were big sellers on Asian Man either. More recently, however, they’ve found a renewed audience. In 2022, LA cassette label 7th Heaven Recordings reissued Ee’s Ramadan to a new generation of listeners, more than 20 years after its original release. Incredibly, the founder of 7th Heaven, Brock Pierce, discovered Korea Girl simply through Spotify’s algorithm. One day when he was about 20, Elizabeth Yi’s anti-organized religion elegy “Under the Sun” popped up in his recommendations. It grabbed him immediately.

“It just reminded me of Pavement and it was really awesome,” Pierce says. “I was curious, so I started digging into more of the band’s history, and I saw that Ee was like a sister band in a sense, where Tobin kept making music.”

He found Mori’s contact info online and got in touch, asking if he’d be interested in having 7th Heaven reissue his discography on cassette. Mori was stunned.

“I was like, ‘What? Who owns a cassette player nowadays?’” he remembers.

Apparently, plenty of people. 7th Heaven sold out of all copies of Ramadan. In 2023, they followed it up with a re-release of Korea Girl’s debut. The full run of cassettes sold out in an hour and a half. Mori wasn’t able to get in touch with some of his old bandmates to work out payment, so he had all proceeds donated to the World Central Kitchen instead.

These days, 7th Heaven is thinking about reprinting all the albums on vinyl.

“I would love, love to do a Korea Girl vinyl,” Pierce says. “Same with Ramadan, too.”

In 2024, Asian Man finally re-pressed the self-titled Korea Girl album on vinyl, themselves. The first pressing sold out within weeks.

Editor’s note: Error in Korea Girl caption fixed after publication.

Wow this is awesome, it’s so cool to see the history of some of my all time favorite bands.