When a work of art makes prominent use of the phrase “hell of” (as well as its derivation “hella”), one could easily expect it to be hardwired with Bay Area DNA. And in the case of webcomic Achewood, it very much is.

Chris Onstad, creator of the beloved cult favorite webcomic, which just returned this May after a sabbatical of several years, spent his formative years in the Bay. Though happily relocated to Portland since 2011, there are still things about his former stomping grounds that he looks back fondly of. The incredible taquerias of Mountain View. Spending time and money at Lee’s Comics. The absurdity of a dinner at the bygone La Fondue.

A decade on, he still has his Silicon Valley area code. And though with typical expat incision, he may have referred to San Jose as an “urban heat sink” during this interview, Achewood could only have been conceived in a place as rife with contradictions as Silicon Valley.

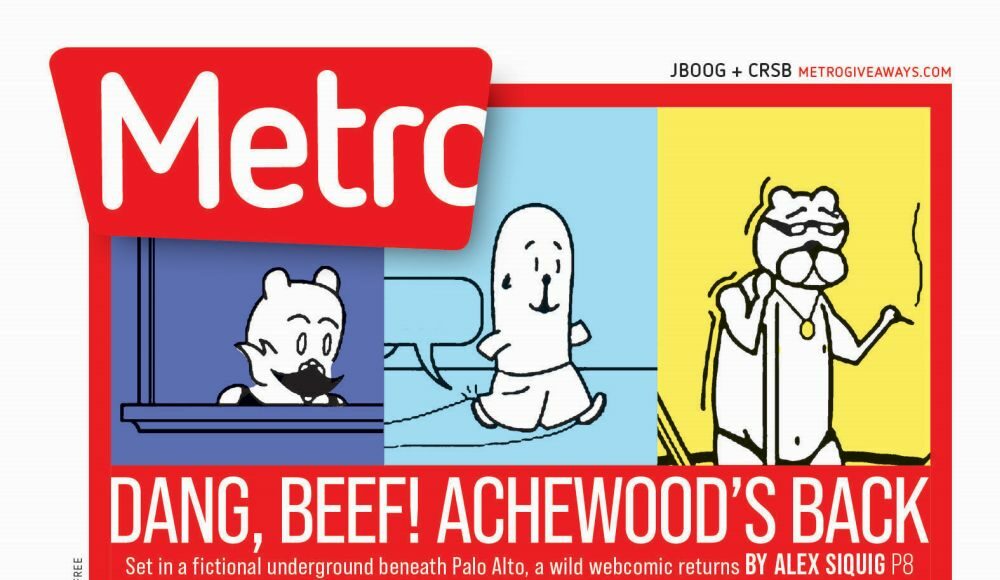

Starring a cast of stuffed animals living in a fictional underground beneath the South Bay, Achewood. You could say broadly that it’s a webcomic (but literary, like a new sort of secret canon) detailing the mundane slice of life adventures of a diverse cast of anthropomorphic weirdos who alternate between drinking and swatting away existential dread in a surreal but boringly familiar world just beyond our own. More specifically, it’s about the friendship of Ray and Roast Beef, the former a wealthy ideas man (cat) with no ideas, and the latter, a computer programmer with self-esteem issues (also a cat). It’s a comic that, past the ribald humor and the dread, teaches us that trouble is a fake idea.

Originally launched in 2001 with a fifteen year run, this summer, the comic unexpectedly returned, with new strips available to Onstad’s Patreon members.

Achewood was born in the shadow of the Campbell Pruneyard. After graduating in English/Creative Writing from Stanford University “by the skin of my teeth,” Onstad found himself, like much of his cohort, embroiled in the world of early 2000s Silicon Valley start-ups. He vividly remembers sitting at a computer lab at Stanford watching someone design the Google logo.

“I was looking at it and thinking oh that poor kid, that logo is so ugly. That company will never be anything.”

Google wasn’t the only future heavyweight disruptor of heretofore-known-reality he rubbed shoulders with at Stanford.

“I was there with the Instagram guys, the Yahoo guys. Every search engine guy was at the parties I was at in college.” Being foisted into this milieu paid off in the short-term. Despite no actual expertise or urge to plunge into the world of tech, that’s exactly what ended up happening.

“If you were at Stanford in ‘97 you couldn’t swing a dead cat without getting a technology job somewhere, even if you were as woefully unqualified as I was,” Onstad says, painting a picture of the dotcom bubble still intact. “I ended up working at Daimler Benz at their research facility on Page Mill Road. Then I did start-ups and stuff like that. I had been writing Achewood on my lunchbreaks walking around the Pruneyard in Campbell.”

Onstad would walk the Pruneyard trail with little notepads from one of his start-ups’ vendors in hand.

“You know if you’re on a long drive or walk or something, you start to disassociate and start having stream of consciousness thoughts? I’d take the pad along to gather that stuff. Then I’d go home at night, and because I was in-house Design Director I knew how to use Adobe Illustrator. I’d take those thoughts and make little panels with coarse drawings of the stuffed animals we had.”

THE LAUNCH

Those little panels of coarse drawings became quite possibly the most enduring web comic of the 21st century. Those who know Achewood, know it very well. If you don’t, it sounds somewhat hyperbolic to explain the impact it had on an entire generation of a certain type of constantly online elder-millennial. It appeared in a transition period, post Y2K, pre-complete domination of every aspect of culture via the Tech Barons. It is a living document of a time just starting to go sepia toned in our collective memory banks.

But Achewood might never have happened at all, had some things went a certain way on a certain day. Onstad’s initial soft-launch of the strip was almost as deflating experience as teenage Roast Beef on a skateboard. Onstad spent the summer getting his ducks in a row and preparing to finally jettison his start-up life in favor of something more creatively rewarding.

“I got a dozen of the first Achewood strips together,” Onstad says, detailing the genesis of the first iteration of the website. “So at two in the morning I sent that page around to my alumni friends, the Comics Journal, everyone I ever worked with and then I went to bed. When I woke up, my wife at the time called me and said two planes just hit the World Trade Center. I had launched (Achewood) on September 11th, 2001. The worst {expletive redacted} launch date you can imagine for a comic. So, nobody wrote me back.”

Yet, the capitalist grind ensured that Onstad couldn’t even mull over his unlucky launch at home. He and his colleagues were required to stay in the office, doubly terrifying, because he worked in one of the Pruneyard towers.

“It’s right by San Jose Airport and the Twin Towers just got hit by airplanes! We can’t work today, that’s suicide. My boss was like, nothing’s happening here, get to work!”

THE RELAUNCH

Achewood relaunched, this time sans terror attack, on October 1st. Onstad was twenty-six years old at the time. Over the next decade plus he devoted himself to exploring the full low shenanigans of man for an audience that became obsessed with his expansive world until the site went silent for what seemed the final time in 2016. Maintaining the strip had become an untenable workload, one that ultimately took the form of stress, anxiety and depression. The comic-strip model of yesteryear (a new update every Monday through Friday) was a recipe for creative burnout.

“I’d read the boards. And invariably for every nice thing, or hundred nice things, someone would shit on it. That was my life for years. No wonder it drove me to insanity and eventually it just burned me.”

But as of May 2023, Achewood is back, this time on Patreon (three different payment tiers depending on the level of your obsession), still honoring a legacy that began at various Bay Area dive bars (Antonio’s Nuthouse, Refuge) and fine dining restaurants, as well as the offices of the Stanford Chapparal in the mid-90s.

The strip is set below the fictional city of Achewood, modeled somewhat after Palo Alto. The Achewood Underground is, in effect, a parallel city that mirrors its aboveground counterpart, but populated by anthropomorphic animals (both stuffed and real) as well as a handful of robots. The core four characters of the original strip, Teodor (stuffed bear, young and full of ennui), Mr. Bear (stuffed bear, old and sophisticated), Lyle (stuffed tiger, drunk), and Philippe (a stuffed otter, permanently a child) live together at 62 Achewood Ct. Each of them is based on real stuffed animals.

Teodor was a childhood toy of Onstad’s ex-wife. He won Lyle at the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk, which befits Lyle’s somewhat menacing, whiskey-stained carny aura. Phillipe was purchased at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, and received his name from wine from the nearby restaurant Fandango. Mr. Bear (Cornelius) was a gift from Onstad’s mother during his college days and spent much of his early life in the trunk of a car. These were the core four that Onstad leaned on as he launched his first post-start-up endeavor.

Like most great things, Achewood took time to find itself. In the early days, the voice wasn’t as distinct, the characters were only partially realized and the strips themselves were typically one-offs, not the serialized overlapping storylines it would morph into. But even in these early, half-realized days of the strip, the humor was of the variety Lie-Bot might refer to as rough chuckles. This was never Cathy or Peanuts (much later Ray would explain to a distraught Charlie Brown that he was dead, pulled into the afterlife by Charles Schultz like an Egyptian Pharaoh), it was always something new, with a mood one might charitably describe as uncertain. Achewood began to evolve into something transcendent with the arrival of a trio of cats, two of whom became the beating heart of the entire immersive world: Raymond Quentin Smuckles and Roast Beef Kazenzakis.

Yes, Roast Beef’s family is Greek and he definitely knows what Ouzo tastes like.

THE BADASS GAMES

In their words, Ray and Beef have been best friends since small times. Ray is an American Curl bedecked in a thong. He’s a wealthy hip-hop mogul with unflagging confidence, despite his pudgy frame and creeping male pattern baldness. Ray loves ladies, the film Braveheart, and crispy beers with the boys. He is an absolute doofus with a generous spirit who once wrote a $10,000 check to Oreos because he likes their product.

“I wanted them to have a little walking around money!” he explains to Roast Beef, the other breakout character of the strip.

Beef is a lanky and very depressed computer programmer who is from circumstances (aka poor). All the confidence the world gave Ray was denied Roast Beef. At times, he is barely functional. In the comic, his bouts of depression are affecting and never used for cheap laughs. Laughs certainly, but not cheap ones. We would be remiss to not mention that Beef’s speech patterns are a bizarre achievement one has to experience first-hand. In a just world, Roast Beef’s dialogue alone should be enough to get Achewood a Pulitzer.

“The core engine of the strip is Ray and Roast Beef,” Onstad says. “The yin and the yang, the positive and negative, they latch onto each other and they spin indefinitely because they’re opposed and yet they share a camshaft or drivetrain.”

The third cat of the trio, Pat Reynolds, is the most obviously unlikable character in the entire Achewood universe (a universe that also features serial killer Nice Pete Cropes). But Onstad has compassion even for the biggest killjoy in the Underground.

“Pat’s in all of us. Every time you’re mad at someone or want to honk at someone, or if you’re at a store and see someone and you’re pissed off and irritated at them, then if you stop, you go like, oh you really just dislike about them something I dislike about myself. {Pat} has to represent that part of our psyche, the id, the loathsome, the bitter, the unfiltered. We all have that.” He shares a strange moment of creative triumph. “I’ve had people who have written to me that said ‘I used to read Pat’s blog and I didn’t even know he was a character in a comic strip, I thought he was just a really interesting asshole.’ I took that to be a badge of honor.”

Achewood is a relic from a different sort of web experience. Not necessarily a better one, but a period when it was much easier to avoid the relentless darkness that now permeates the routine act of “going online.” This was the message board era, the RSS feed era, the raw materials coalescing that eventually distorted into what we now know as social media, which dominates our daily lives with a goofy iron fist. Achewood was something dangerous, something that could spread only with early Web word-of-mouth.

It remains difficult to explain how brilliantly it elevates psychic pain to highbrow art. As it got its sea legs, Achewood became deeply surrealist longform storytelling Trojan Horsed via the quotidian hang-outs of stuffed animals, cats, a manic strung-out squirrel, robots and other charmingly off-kilter malcontents. Over the years they were lost and found and lost again. Punchlines were optional, unpredictable. It felt like a paradigm shifting sort of humor, the vanguard to something new like the Simpsons or Mr. Show or later, Tim and Eric, but even typing “paradigm shifting” does it a disservice. Achewood was never about out-smarting you, even though it was definitely smarter than you.

Despite being extremely raw and teeming with darkness, there was a decency to it, seen especially in the decidedly non-toxic friendship of Ray and Roast Beef. Sure, reading Achewood could sometimes feel like a gentle slap in the face, a hug maybe slightly too rough, or the rug being pulled out from under you but for the most noble purpose possible.

Eventually the strip would expand beyond a webcomic to encapsulate a miniature empire of content. Blogs written by the characters in their unique voices launched in 2004. Achewood cookbooks dropped, as was only appropriate for a strip populated by amateur gourmands. While Ostad was working at Daimler Benz, it was the beginning of the Food Network Revolution and he took advantage of his business trips.

“I would go to different places with an expense account, and I’d take Zagat Guides and bootstrap myself into an appreciation of cuisine.”

That culinary appreciation filtered down to his characters, and recipes are available for Ray’s Beer Can Chicken, Teodor’s Lamb Kofte, Mr. Bear’s Smoked Salmon on Potato coins, or the Childhood Sandwich, from the damaged mind of Roast Beef.Speaking of that damaged mind, one can even buy multiple issues of Roast Beef’s zine Man Why You Got To Even Do A Thing. Ray wrote a real advice column (real humans ask, fictional cartoon cat answers) for years and even when Ray is being a goofball, nuggets of real wisdom burst through the bit.

Just as Greek schoolboys in antiquity were expected to summon apropos passages of Homer by memory, so too can Achewood connoisseurs dredge up their embedded knowledge of storylines and characters and especially dialogue. There is a seductive power in Onstad’s language, the various distinct rhythms and unmistakable voices of the various interlocutors. The dialogue is idiosyncratic crass poetry, quirky but never precious, straight-to-the-point but needlessly verbose, but never hamfisted or excessively sentimental. The mythology is equally rich. One does not forget the Great Outdoor Fight (or the Great Indoor Fight, as Cornelius dubs marriage) or the surreal turn of the Cartilage Head arc with it’s nearly as bonkers B-story featuring Ray challenging the founder of Williams-Sonoma to a contest of writing Sapphic raunch, or even the gag that started it all, Phillipe standing on it.

FAST TIMES

Chris Onstad arrived at Stanford from Danville the summer of 1993. Soon after, he discovered The Stanford Chapparal (or “Chappie”), the university’s humor magazine, which has been in operation since 1899.

Onstad describes his initial impression of the magazine as “kind of punk rock.” It was irreverent, intelligent and gave him something to go to school for. His sophomore year, he was named co-editor of the Chapparal, along with Eric Saxon, whom he had met at a party where they bonded over Late Night With David Letterman: The Book. It was Saxon, according to Onstad, who originally coined the name Achewood as a play on wormwood, the active ingredient in absinthe.

“Chris took the word from one of my emails in 2001, an ad-libbed neologism he thought sounded like a title of a comic strip.”

Saxon recognized the potential nearly immediately.

“Chris has a great balance of the Apollonian and Dionysian,” Saxon says. “He can pull deep from somewhere in his subconscious and is receptive to strangeness, then keep that in place as he meticulously crafts something that can be appreciated by everybody, with strong stories, jokes and characters.”

However, not everybody at Stanford was on the same page.

“Our ideas for the magazine tended to go in a different direction than the senior leadership and traditional college humor,” Saxon says. “I think we were influenced by the alternative comics of the early to mid-1990s, plus alternative music and its various subgenres,” which of course explains young Roast Beef’s iconic Dead Kennedys t-shirt.

Today, Onstad is grateful for his time at The Chapparal.

“It’s one of the few incubators on the American landscape where you actually spend time working on the craft of humor and satire writing. The magazine kind of saved my life,” he says.

It certainly changed it.

THE GUY WHO SUCKS

Thus far, the new iteration of Achewood can be counted a success. The characters feel as fresh as they did in the early 2000s. It’s almost like one of your favorite bands reforming after a long breakup: the songs are a bit different, maybe the tempo has changed slightly, but it’s still recognizably the thing that got its hooks into you all those years ago. Also, Winnie the Pooh gets killed early on.

In a modern landscape where art often stands in for some sort of affirmation of a worldview (whether good or more commonly these days, very bad), Achewood still feels non-partisan in the most wholesome, un-preachy way. At its center it is a story about a bunch of damaged misfits who form a bizarre surrogate family. They just happen to be depressed cats, Motorhead loving stuffed tigers, or sex-crazed robots. Onstad uses these myriad somewhat down-and-out characters to take aim on the folly of being alive in a deeply, deeply weird world. No one is especially targeted, nor is anyone especially spared. That’s what satirists do.

“Everybody’s gotta have the piss taken out of them,” Onstad says, reflecting on the animating purpose of satire.

MAGICAL REALISM

An unlikely contributor to the resurrection of Achewood is A.I. Around the time non-billionaire class of humans were freaking out about ChatGPT and getting duly terrified of the world-altering implications of Artificial Intelligence in the wrong, money-grubbing hands, Onstad zigged when so many others zagged, and found a useful application for the burgeoning behemoth.

A business collaborator that Onstad was working with to break into the Japanese market informed Onstad of a curious amount of A.I. developers among his Twitter followers. And a possible solution to a long-time problem sneakily revealed itself.

The stress of deadlines and pressure to create the sort of complex, literary content the fans had come to expect had taken a toll over the years. Molding the rich universe of Achewood with all the right algorithms could spit out a reasonable facsimile of Onstad-brand humor, without ever being in danger of replicating the real thing. A.I. became a way to get the creative juices flowing again, without using technology to simply cheat the process by outsourcing the content to a robot sidekick.

With the help of a group of engineers (who, allegedly, are all real Achewood heads), the idea of the RayBot was born. Taking many years’ worth of content from Ray’s hilariously hedonistic and considerate Advice Column, an AI bot (the aforementioned RayBot) took shape, dispensing guidance in the style and idiomatic tenor of Ray.

The accuracy of the voice shocked Onstad.

“I was floored. It could get about 80% sounding like Ray. A lot of creativity and range. A sea change of what sophistication machines can develop.”

Onstad realized very quickly however that A.I.’s reputation for evil preceded it.

“We launched right when we launched the new Achewood on Patreon, which was a terrible idea.”

Many diehards, despite clearly his attempts to explain this was categorically not the case, believed Onstad to be using A.I. to create content for the strip. He had to do damage control, repeatedly reassuring his fans that the notion he wasn’t completely in control of Achewood was absolutely untrue.

“Some people said A.I. is evil and even using it in any regard is bad. Whatever! Basically, A.I. is extremely powerful, it’s going to absolutely change the work landscape and people are going to have to adapt. It will change things. Probably at a very rapid pace. Because we live in a news saturated world, most of the headlines are bogus. It’s not going to destroy the world.”

“Anytime soon,” he adds quietly.

In the final analysis, he declares the A.I. experiment as a positive experience.

“A.I. is a useful tool,” he says, adding, “I don’t need it. I like to write. I don’t want something to offload the work.”

OREGON TRAIL

Onstad has no regrets about leaving the Bay Area for Portland in 2009. It was time to put the “alien landscape of software, venture capital and lawyers” in the rearview mirror and start the next chapter. Silicon Valley was changing. “It was a pressure cooker of a place.”

There is some sadness and resignation in his voice when he thinks back on his former home. All the places that inspired his magnum opus feel far away. “All the beautiful, Bohemian things are gone. Long, long gone.”

He’s not completely right about that, but even if he was, that doesn’t mean he’d be right forever. Achewood itself is a beautiful bohemian thing that was once gone, but clawed its way back to us.