After the Grateful Dead played their farewell shows at San Francisco’s Winterland in October 1974, its members broke off into side projects, reverting from stadium tours to club shows up and down the California coast. Jerry Garcia gigged with pianist Nicky Hopkins and bassist John Kahn. Phil Lesh explored electronic psychedelia with the album Seastones. Bob Weir joined the Dead offshoot band Kingfish.

With Kingfish, Weir played Los Gatos’ Chateau Liberté; Sophie’s in Palo Alto; the Odyssey Room in Sunnyvale; the Bodega in Campbell; and in Santa Cruz, Margarita’s and the Crown College Dining Commons at UC Santa Cruz. 1975 was a busy year, and somehow the Dead also recorded the amazingly ethereal Blues for Allah at their San Rafael practice hall.

Weir was handsome and focused and, even as the Dead resumed touring, pulled together a solo album, Heaven Help the Fool, with L.A. session musicians Waddy Wachtel and Tom Scott. Supermodel fashion photographer Richard Avedon shot the cover. It charted respectably, though critics derided it as “California mellow.”

Ultimately, Weir forwent a solo career to remain a sideman in a band of hairy hippies with an improbable trajectory—one that connected the 1950s literary Beats to the Haight-Ashbury counterculture and Silicon Valley’s LSD-influenced innovation culture. With future cyber pioneer John Perry Barlow, Weir composed “Cassidy,” inspired in part by the valley’s rail legend and spoken-word poet Neal Cassady.

He was long overshadowed by the mystical deity Jerry Garcia, whom he first encountered at Dana Morgan’s Music Store at 534 Bryant Street in Palo Alto—where the Duxiana luxury mattress store now sells beds that can cost $10,000, or multiples of that. First playing as the Warlocks, a jug band, they performed their first show as the Grateful Dead 60 years ago at a house moved to make way for San Jose City Hall, where a plaque was installed last month.

Weir was raised in Atherton by adoptive parents who didn’t understand his “pathologically anti-authoritarian” inclinations. He left high school to run off with Ken Kesey’s Pranksters, lived in a communal house in San Francisco, and, as he told it in the autobiographical Netflix documentary The Other One, “I took LSD every Saturday for a year without fail.”

After Garcia’s untimely death at 53 in 1995, Weir developed confidence as a carrier of the torch, as well as as a musician, rising to new heights with Dead & Company shows alongside John Mayer. Together they performed at Shoreline Amphitheatre, Las Vegas’ Sphere and Golden Gate Park. In 2015, he reunited with Lesh to play the 50th Anniversary Fare Thee Well shows at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara and Soldier Field in Chicago. Weir also played smaller venues, including Stanford’s Frost Amphitheater, Oakland’s Fox Theater and the Sweetwater in Mill Valley, where he lived and owned the music hall.

Along the way, he found love and started a family, becoming a father the year he turned 50. He located and connected with his birth father and pursued philanthropic work through the Furthur Foundation. He died four days ago, on January 10, 2026 at the age of 78.

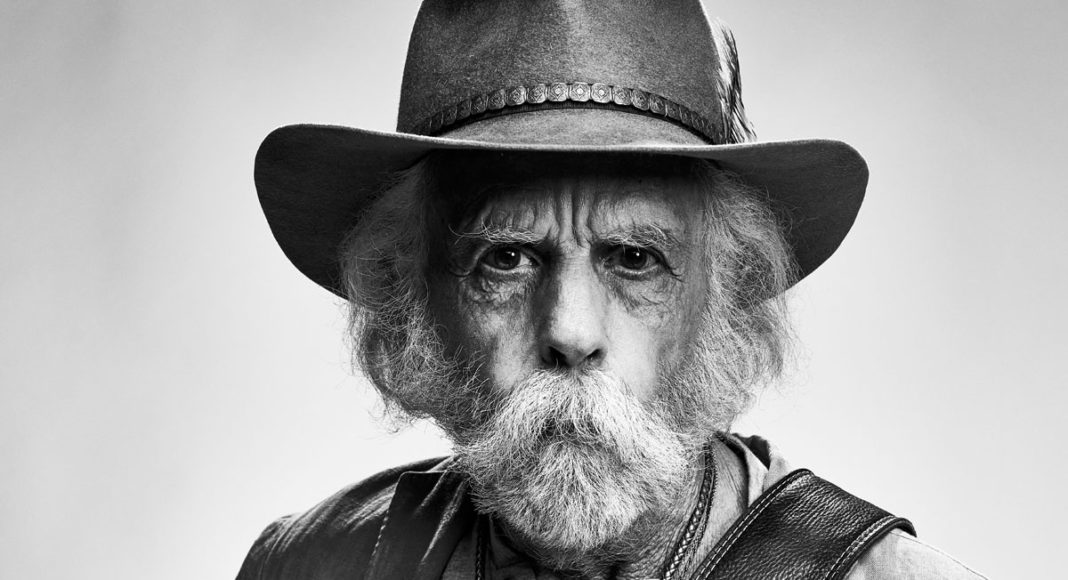

He stayed humble, walking onstage in shorts and sandals, growing a handlebar and aging gracefully. And while his musicianship never screamed for attention amid the amazing array of talent that always surrounded him, it’s now clear to see. Just listen to “Sugar Magnolia,” “Truckin’,” “Playing in the Band,” “Looks Like Rain” or “One More Saturday Night,” and Weir’s stature as an American rock musician holds its own with any of the greats.

“I don’t trust pride,” he said in the documentary about his life. “But when you realize that we are all one, you can be proud of being part of that gigantic entity that we all are.

“Life has endless depth to it. Endless resonances and reverberations throughout time and space. And making sense of all that is something that I’m just sort of taking my time doing. My life has kind of been instructing me to look for the timeless.

“That’s what I’m chasing.”

Other Tributes to Bob Weir