The eye instinctively traces a curve, what looks like a spine hidden in lovely, firm, dark flesh. From the blade of what must be a shoulder, it continues down, expecting a nude buttock, the model turned away from the camera with her legs tucked in, only to find instead…a stem.

It’s not a surrealist painting. It’s a photo of a poblano pepper turned on its head, photographed in sensual lighting, transformed by imagination.

Well-known photographers like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston were renowned for their views of California’s landscapes. However, they and other photographers in the same orbit were heavily influenced by the surrealist movement often encapsulated by painters like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. Reality Makes Them Dream, a new exhibition of 1930s American photography at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University recontextualizes the work of these photographic titans through the lens of surrealism.

Though 1930s photography is often known for its gritty realism, Josie Johnson, the exhibit’s curator, sees a dream-like quality in their stark black and white portraits, like Dorothea Lange’s famous “Migrant Mother.”

“Photography at the time focused on the reality in front of the lens, and yet, they still want you to have that imaginative length that takes you somewhere else mentally, that makes you imagine kind of a different world,” Johnson says.

In addition to challenging preconceived ideas about 1930s photography and the people behind the lens, Johnson wanted to challenge the prevalence of white, male, Anglo-Saxon photographers in the narrative of the 1930s photo scene.

Chao-Chen Yang arrived as a Chinese diplomat in Chicago and became a photographer enamored with the romanticism and surrealism of the American West. Seema Weatherwax, a Ukrainian Jewish refugee, worked as Ansel Adams’ darkroom assistant and took her own fantastical portraits of Yosemite’s natural beauty. John Gutmann, also Jewish, escaped Germany just as Nazis came to power. His photos, while couched in the realism of 1930s portraiture and street photography, take on an Orwellian surrealism and justified paranoia.

Japanese American photographer Kyo Koike, meanwhile, was enamored of Mt. Rainier, which he considered his personal Mt. Fuji. His foggy mountain photos have a curiously alien quality, as though Koike was an explorer discovering another world.

Koike was incarcerated along with hundreds of Japanese citizens after Executive Order 9066, and died shortly thereafter in 1947 at the age of 69, having never recovered from the trauma of internment.

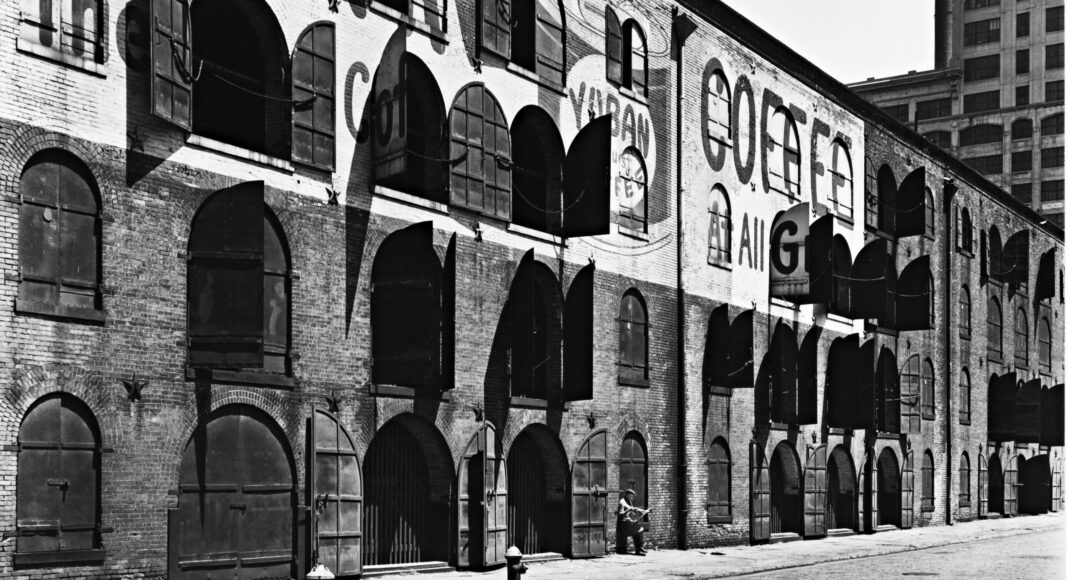

The exhibition also explores themes of sex, race, the mythologizing of the American West and the Native American, the endurance of the imaginations of children during the Great Depression, the allure of nature as a relic of our past and the wonder of the city as a harbinger of our future. It also echoes our own 21st century uncertainty, standing at the precipice of unfettered innovation, looking backward to simpler times.

In her foreword to the exhibition, Johnson argues that although the exhibit’s photographers didn’t use any of the available visual illusions of the time, their photography was not intended as pure documentary—even when Marion Post Wolcott and Sonya Noskowiak were taking their photos for government agencies.

“A key goal for artists of this period was to use photography to ignite the imagination, even while pursuing an increasingly direct approach to their subjects that mirrored the world as they saw it,” Johnson writes.

Like a symphony composed of movements, the exhibition is organized into seven sections: Natural Wonders, Divine Figures, Everyday Splendors, Living Relics, The World of Tomorrow, Street Theater and Surreal Encounters.

Though these sections contain their own themes, certain works seem to call out to one another from across the spacious gallery. The threads connecting the exhibit’s pieces are not one but many. They demand the viewer travel back and forth several times, each time seeing the most familiar subjects as more and more surreal and otherworldly.

Torn between the stark reality of the Great Depression and a dreamscape of rising cities, what other way could artists of the 1930s see the world?

Opens Wed, 11am, Free

Cantor Arts, Stanford