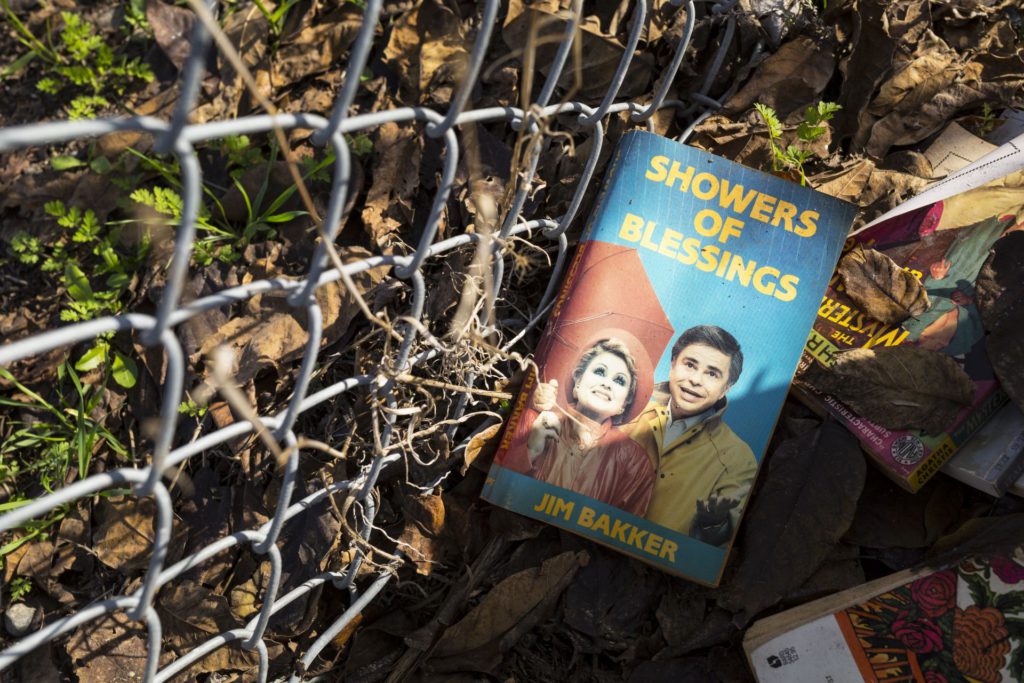

A blank mango wall backdrops a decrepit payphone. Sun-wrecked wooden signage at a used car lot rises like an abandoned ship’s mast into the sky. Several waterlogged paperbacks are dumped in a parking strip. These are the subjects of Josh Marcotte’s photography, also known as Lost San Jose.

Anyone can take photos of rose gardens or Turkey Trots. Not Marcotte, who instead fixates on a vacant dry cleaner building with a classic neon sign that everyone recognizes and loves, that is, everyone except the landlord.

At least 20 years ago, in a San Jose that predated influencer culture, selfies, memes and click-bait promoters, Josh Marcotte created a brand at the forefront of urban decay photography. Deceptively simple, Lost San Jose was pure lowbrow poetry: simultaneously ahead of and behind its local time. Even he cannot pinpoint the moment it started. The adventure is and was beginningless.

“I’ve never been in a huge hurry with this project,” Marcotte told me. “It’s something that I did for years and I never shared with anyone.”

Yet somewhere around 2008, the Lost San Jose nom de plume began to appear in local galleries like Kaleid and even denim shops in Santana Row. Then came Instagram and away it went. The work resonated far beyond Marcotte’s original intentions. While more established worldly photographers glommed onto what became known as “ruin porn,” no other native San Josean seemed so in tune with the sheer beauty of mundane scenes, tired storefronts, crooked viewpoints and the washed-out glory of San Jose’s constantly changing landscape.

After a hiatus of sorts, during which Marcotte seemed to disappear from the social media barrage, he’s now returned in full force, with a heroic mission: More than 300 images from the gritty underbelly of San Jose all over the Triton Museum walls. The resulting show, “The Same Streets Everyday,” opens this weekend.

“This isn’t going to be like, you walk in and there’s 15 photos,” Marcotte said. “It’s going to be clusters, different sizes, different formats. And I’ve been given the entire rotunda in the gallery when you first walk in, and so I’m hoping to fill that entire rotunda as much as I can with images. Just so much on the walls. Just really fill that space up and showcase the last 15-plus years’ worth of photos that I’ve taken, of this 20-plus year project.”

SAN JOSE GRIT

When Instagram first started, the app was primarily intended for photographers, not obnoxious narcissists taking selfies every day. Yet even then, no one else in San Jose was better at using the app to demonstrate photographs from the bland interstices of suburbia.

As a result, Marcotte developed a serious local following. To this day, many natives can instantly recognize his imagery.

“I like that he doesn’t sugarcoat it,” said Vanessa Callanta, the Triton Museum curator who organized the show. “I had been following him online for years and his work really caught my eye just because you see so much beautiful photography—like beautiful landscapes, everyone wants to capture beauty and things—but Josh, he just shows it as it is.”

Especially in San Jose, where every native eventually arrives at a point in life when they realize much of the recognizable landscape from their childhood is now gone, hardly any sugar is left to coat anything with. Lost San Jose becomes not just one particular photographer’s brand, not just Marcotte’s personal view, but an entire civic state of mind.

This is why you won’t see his name anywhere in the text panels at the museum. After 20 years, the imagery has long since evolved into something far beyond just him. There’s a resounding local universality about it, almost as if the entire body of work now belongs to every San Josean. And everyone is encouraged to go out and capture the ignored, the lost, the underrepresented realms of the everyday San Jose condition, and be proud of it all.

This is also why tourism bureaus and chambers of commerce rarely understand how or why this type of imagery resonates so much with people. As a curator, Callanta understood immediately.

“I’m not from here, I’m actually from the Philippines, but I grew up in the Bay Area,” she said. “And so seeing his images, it’s like, ‘Oh, I’ve been there, I’ve passed by that.’ But it makes you take another look at that area. This is what I want people to see. I want them to see not only the beauty of their hometowns, but I want them to see everything about their hometowns.”

As such, “The Same Streets Everyday” naturally emerged from several years of photography and many hours of documentation, often capturing just what had changed as Marcotte explored his neighborhoods. In some cases, the same cracked sidewalk or the same broken piece of fencing was still there 10 years later, while in other cases, objects were so fleeting they simply disappeared over the years, or were moved somewhere else, like in the case of a rusty old car. The fragments became the environment that surrounded him, an environment that will now grace the walls of the Triton Museum.

“It’s the things that you see when you walk every single day through the same neighborhoods over and over again,” Marcotte said, admitting he purposely takes wrong turns or segues behind buildings rather than the front, or even takes different paths to get to work. “Some of it’s purposely getting lost and seeing what’s out there,” he continued. “This is how to get from point A to point B. This is the walk I take every day, and it’s the things that I see that make up my environment and what San Jose is to me through where I live, where I work, where I shop, where I happen to be.”

THE ROOTS

For Marcotte, it all began with the most iconic symbol of suburban wasteland America: the lawnmower. As a fourth generation San Josean who had never left the bubble of suburbia, Marcotte would often spend time with his grandfather on the weekends, mowing the lawn and doing yard work, but also listening to the amazing stories that came out of his grandfather’s memory bank.

Instead of being turned off by the same old tales over and over, Marcotte was fascinated. His grandfather was a self-proclaimed San Jose historian with a wealth of material to pass on. By the time Marcotte arrived at San Jose State, he began to explore the city on his own. He went looking for the places his grandfather had mentioned, much of which was now in various states of disrepair, creating a serious disconnect between what his grandfather shared and what still remained.

After writing stories, poems, short stories or memoir pieces about the things he saw and the people he met, Marcotte slowly shifted to photography. His dad was an engineer, like many of his generation in Silicon Valley, but also had a photography business on the weekends, shooting weddings, portraits and similar jobs.

“As the years went on, I started spending more time taking photographs and less time writing, and that’s where the project began,” Marcotte said. “It was trying to connect with the stories that my grandfather had told me, trying to understand the family history, the ghosts of my family that were out there on the street and transition into exploring and trying to understand San Jose, not just from my grandfather’s perspective, but from mine, from my point of view.”

Like many people, Marcotte began by shooting the buildings, signs and neighborhoods everyone knew, but eventually migrated to the off-kilter fragments and the artifacts that comprised everyday life, the neighborhoods he frequented, the perspectives and landscapes that characterized San Jose for him, beyond the iconic, the known or the touristy brochure-style crud.

That was over 20 years ago and the project has never really concluded. Marcotte continues to document San Jose life as he sees it. There is no end or beginning.

“At this point, I’ve used more than a dozen cameras,” he said. “It’s been digital. It’s been film. It’s been instant photos, it’s been a lot of different formats, but it’s always the same subject most days, which is San Jose.”

THE VENUE

The Triton Museum was built specifically for art shows. It’s not a repurposed building that was later converted into a museum. The rotunda in particular works extremely well for photography. Due to massive amounts of natural light and triple UV protected glass, even if the museum is closed, anyone can stand outside, peer in and view the Lost San Jose oeuvre of empty storefronts, rusty shopping carts or busted neon signage.

“We have this lovely park out back and people will walk by and I’ll see them staring at the inside of our museum through the glass, and then it gets them to come inside,” Callantra said. “But I think just seeing his art, as well, through [the windows] will kind of intrigue people and get them to come in and take a closer look.”

In the rotunda, constellations of Lost San Jose imagery will appear in various places, triggering viewers to make their own connections. The walls are not continuous, which breaks up the clusters in just the right fashion. Viewers will start to notice patterns. A building included in one cluster might reappear in another group of photos, but with two different cars parked in front of it. Payphones or neon signs might show up in more than one cluster. Attendees will recognize just how specific neighborhoods have changed over the years, or haven’t changed at all.

When viewing 300-plus Lost San Jose photos, the mundane begins to achieve a numinous quality. The ego dissolves. There are no selfies. Even nonnatives will unearth a degree of Zen-like universality in the work.

“If you’re walking around any metropolitan city or urban area, these are not things that you wouldn’t see anywhere else,” Callantra said. “So it’s just really interesting to see his perspective on his hometown and community. And I want to know if other people will have that same perspective and what they’ll take away from it.”

In the end, there still isn’t one. Expect another 20 years of Lost San Jose. Why hurry?

Jan. 20—May 12

Free admission

Rotunda Gallery, Triton Museum

1505 Warburton Ave, Santa Clara

Tues—Sun, 11am—4:30pm

When is the Lost San Jose exhibit on view.

GREAT ARTICLE GARY,!!!!!!!!, 👍

Sounds and looks very good, lived in San Jose all my life till 2004 I have asked this question to many related articles including The San Jose History Museum, anyone out there have any old pictures of “Trader Lou’s Amusement Park” it was on Monterey Rd. just north of the Capitol drive-ins on the east side of the street, late 50s till around maybe 65ish ? Thanks Very Much….