In the fall of 2017, a curious library patron walked into the California Room on the fifth floor of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library with a simple question: Did the library have any information on the history of lowrider culture in San Jose?

Staff were surprised to find that they did not. The California Room, part of the San Jose Public Library system, specializes in the documenting and preserving the history of the Golden State, with a specific focus on San Jose and Santa Clara County. They’ve compiled a vast digital library of historic photos, city plans and other cultural ephemerasuch as the brightly colored labels that once adorned fruit crates shipped from South Bay orchards.

They also have collected many physical artifacts. Most recently, Estella Inda, a clerk with the California Room, worked on compiling a number of paintings by San Jose artist Edith Harvey Heron.

When it came to lowriders, however, “the history was missing,” Inda says. It was a glaring blindspot, and in short order Inda was assigned to correct it.

While figures such as Cesar Chavez and Luis Valdez loom large in the narrative arc of this city’s rich Latin-American history, one cannot paint a truly accurate mural of San Jose without including the uniquely Chicano tradition of the lowrider.

It took Inda more than a year and a half to amass the materials now on display in “Story & King: San Jose’s Lowriding Culture,” a multi-floor exhibit at the MLK Library. The hardest part, she says, was getting people to respond to her requests for materials. Many of those she sought had moved out of the area and didn’t have Facebook accounts or email address that she could readily look up. Nonetheless, Inda pressed on. And in the end, around 100 people contributed to the exhibit.

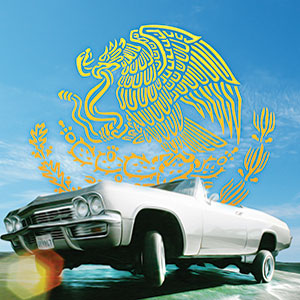

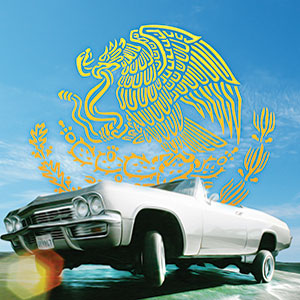

“Story & King,” which runs through the end of March, features issues of Lowrider, art by “Homies” creator David Gonzales, custom car parts and other ephemeralike flyers for lowrider shows, photographs, and newspaper clippings documenting the rise of lowrider culture. On the whole, the exhibit celebrates the lowrider for what it is: a labor of love, a communal symbol and a work of art.

TOTALED

For Inda, the low and slow cruise through San Jose’s lowriding history may have started with a question. But for Suzanne Lopez, it began with the car accident.

“What happened was my older sister got into a car crash in our family station wagon,” says Lopez, whose photos of lowriders are currently displayed on the second floor of the King Library.

Rosemary, Suzanne’s sister, was only 16 years old at the time. Raised by a single mother, she had been out running errands for the family when someone ran a red light on Ocala Avenue, smashing into her car from behind. The station wagon was totaled.

“So my mom and my tía went to look for cars,” Lopez recalls. “She found that ’67 Impala and she just fell in love.”

Later that day her mom came home with the Super Sport. It had a blue interior, an eight-track player and a speaker in the center of the rear bench seata curious design quirk that those familiar with vintage Impalas may recall.

Lopez didn’t know it then, but that car would change her life forever. It was 1972, and lowriding was about to explode all over the West Coast. Lopez’s 77 photosculled from close to three decades of documenting Northern California’s lowrider scenefeature slouchy Chevys, bouncy Buicks, hundred-spoke rims and all manner of custom cars.

Many of the photos were taken at local lowriding events, often in an around the intersection of Story and King streets. Lopez calls this area in East Side San Jose “the mecca of lowriding”and with good reason.

CULTURAL CREATIVITY

The deepest roots of Chicano car culture can be traced back to Southern California. And yet, at the height its popularity, East Side San Josespecifically the intersection of Story and King roadswas arguably the center of the lowriding universe. At least according to Robert Velasco, owner of RS Hydraulics in San Jose.

“People came from everywhere,” Velasco says, recalling his glory days on the scene. “Frisco, Sacramento, Salinas, Fresnojust to cruise on our boulevard.”

In addition to being one of the most important cruising hotspots on the West Coast, San Jose also gave birth to Lowrider magazine, the “Homies” line of illustrated characters and figurines, and a number of other technological and aesthetic innovations.

RS Hydraulics may just be the only custom auto shop in San Jose still specializing in classic lowriders. Velasco, the garage’s owner, has been involved in local lowriding since its earliest days. He lights up as he reminisces about the first time he saw a lowrider.

It was the late ’70s and he was a teenager working in his father’s auto shop on Santa Clara Street. Lowrider Hydraulics, owned by local lowriding pioneer Steve Miller, was just across the street, and the young Velasco took a keen interest.

“I was totally infatuated,” he remembers.

Velasco started working for Miller when he was about 15 years oldaround the same time he bought his first car, a 1963 Chevrolet Impala.

After putting in the requisite work to get it up and running, Velasco proceeded to transform his car into a lowrider. His father was taken aback. “He couldn’t believe what I did,” Velasco remembers. “He couldn’t believe I cut it up for hydraulics.”

The way Velasco tells it, though Chicano car culture was strong during his father’s generation, lowriding was something that he and his peers did to make the cars their own. And it was hard work.

“It takes a lot of modification,” Velasco says, explaining the various innovations and workarounds that lowrider shops had to develop in order to get their cars to go so low.

At first, shops simply put smaller wheels on their cars to achieve a lower profile. But eventually that wasn’t enough. People wanted to keep larger tires on their rides while still dropping them low, so people like Miller and other lowrider shop owners started getting creative with welding torches.

Velasco points to the undercarriage of a car he has raised up in his shop. Near the point where the axel meets the wheel, the car’s frame has been altered to allow the top of the tire to disappear up into the wheel well. Velasco calls the feature a “C notch,” because it resembles the letter C turned clockwise by 90 degrees.

Hydraulics are another automotive technology advanced by the lowrider community. Filled with pressurized oil and powered by a battalion of car batteries, hydraulics are used to raise and lower custom cars, and to keep them riding smoothly when driven at higher speeds. Later on, these hydraulics were suped-up to the extreme, which gave vehicles the ability to leap off the ground or strike a stationary, three-wheel pose, with a single tire lifted off the pavement.

By the time Velasco had opened his shop in 2003, fewer people were interested explosive jumping power, though they still wanted an ultra-smooth ride and to be able to set their cars low to the ground. The trend was moving away from liquid hydraulics to pressurized-air suspension systems.

Being from the old school, but also possessing an interest in new technology, Velasco set out to create a system of air-powered lifts that could achieve the same three-wheel pose of traditional hydraulics.

“People were telling me that an air-ride suspension couldn’t do a three-wheel,” he says. “I never believed that.”

In 2007, Lowrider, ran a multi-page spread titled “Three Wheelin’ With Air,” praising Velasco for his innovative technique. “I knew it could be done,” he says. “I just had to put my brain to work a little bit.”

LIBRARY LOWRIDING

On a rainy January evening, room 225 at the MLK library is packed. Tonight’s event, “Out of the Past: San Jose’s Lowrider History,” is a panel discussion featuring many of San Jose’s earliest lowrider influencers. Ten minutes before the talk begins, the space has become a sea of checkered flannel shirts, beanies and flat-brimmed baseball caps. Many in attendance are from San Jose, but others have come from Oakland, Fresno, and even Arizona. By the time the event kicks off, an overflow room has opened to accommodate the crowd.

The first speaker of the night is a sprightly woman with springy two-tone hair: Biney Ruiz, an early promoter of local lowriding events.

“Are you ready for showtime?” she shouts. The room erupts in cheers.

Ruiz is now in her 60s, but back in 1973 she was a young student at San Jose City College. A native of the city, she was an active member of the school’s MEChA chapter. An acronym for “Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán,” the national student organization was born out of the broader Chicano Movement in the late ’60s,

“We were always doing benefits,” Ruiz remembers. Community dances, food drivesthe normal fare for college clubs. “I realized after time that there was a lot of work to do,” she says. “So I did it.”

In between her actual college classes, Ruiz found herself getting a crash course in event promotion. As she took on more and more responsibilities with MEChA, she learned more and more about promotion.

By 1975, when Ruiz started throwing her own events, lowriding had officially taken off. On weekends, it was common to see traffic grind to a halt for blocks around King and Story roadsa sea of cars held in place as people flocked from all over the Bay Area and beyond. It’s difficult to confirm actual numbers, but folklore maintains up to 15,000 people would show up on weekends just to cruise Story and King.

Ruiz quickly realized that she was bearing witness to the dawn of a cultural movement.

In early 1976, under the name 5 Star Productions, Ruiz started throwing some of the first events targeted to the lowrider community. “I was the first to create the lowrider market, with the help of the car clubs,” Ruiz says.

It began with dances, but quickly grew in scale and ambition.Together with members from the New Style lowrider car club, Ruiz created the first lowrider scoresheet that was used to judge lowriders at the car shows, and 5 Star Productions gave trophies for the best custom paint, interior, upholstery, undercarriage and many more categories.

A collection of fliers from 5 Star events makes up a large portion of the material in the “King and Story” exhibit, including one event that made headlines.

At the end of 1977, Ruiz recalls helping to organize a lowrider caravan with radio station KOME. “The police were involved,” she says. “They escorted the lowriders from Evergreen Valley College to the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds and stopped traffic at the intersections . When I say escorted, there were caravans I had earlier, but this was like as if there was a funeral.”

An article in the Mercury from the time records that more than 500 cars took part in the lowrider caravan. Whole streets were shut down. It was without a doubt the highest-profile production Ruiz ever put on. But by that time, Ruiz had already started something even bigger, something beyond the scope of just San Jose.

“These car clubs were popping up everywhereSan Francisco, Sacramento, Oakland, Pittsburg, the Central Valley,” Ruiz recalls. “In the beginning I was just handing out fliers on the street at Story and King every weekend, and I put posters up on the poles. Soon, I created the Lowrider Bulletin.”

The Lowrider Bulletin was a mailer compiled and designed by Ruiz. In it, she detailed any and all upcoming events connected to lowriding, car clubs and the overarching culture. It was mailed out to all the lowrider car clubs she could find in Northern and Central California. At the time, there there were 700 clubs on the mailing list.

While Lowrider might be the biggest publication to emerge from the San Jose scene, it was Ruiz’s Lowrider Bulletin that first united all of California’s various car clubs, taking something that was regional and fragmentary, and making it into a connected culture. Without Ruiz, many of these groups wouldn’t have even known the others existed, and lowriding wouldn’t have become the internationally recognized culture it is today. Though she never drove one herself, the cultivation of the lowriding culture would be Ruiz’s lifework.

“It was a beautiful time,” she says, at the end of her presentation. “The lowrider movement was something I was blessed to be a part of.”

HORSE POWER

To understand the meaning of lowriding, we have to go back. Back before the ’70s heyday of King and Story, back before the era of the bombs (those big, hulking cruisers from the ’20s-’50s), back even before the car existed at all.

“Of course, as well all know, the car is nothing more than an extension of the horsea motorized version of the horse,” says Arturo Villarreal.

Villarreal is an ethnic studies professor at Evergreen Valley College. With a focus on Chicano culture, Villarreal has a vast knowledge of California history. In the figure of the 20th (and 21st) century lowrider, Villarreal sees many parallels and overlaps with the vaqueros (cowboys) and charros (horsemen) of Mexico’s past.

“A lot of the same principles, care and attention that were given to the horse by the vaquero and the charro, you can find given to the lowrider by the lowriders,” Villarreal says.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the horse in Mexican culture. Beginning when the horse was introduced to the continent more than 500 years ago, horsemanship has been a principal part of Mexico. In the colonial era, it was a way of demonstrating prowess and knowledge, and a skill that promised upward mobility. To the charro, the horse was much more than an animal: it was a body of knowledge, a set of rituals, and a way of life. To this day, charrería (a competitive event similar to a rodeo) is the national sport of Mexico.

If the horse in vaquero culture is the equivalent of the car to the lowrider (a show of craft, care and knowledge) then the paseo is the equivalent of the cruise.

“The paseo is a ritual that usually took place on Sunday, at the plaza,” Villarreal says.

On Sundays, men and women of all ages would come to the plaza at the center of town to socialize, and to see the charros show off their horses.

“The females would stroll around in one direction, and the males in the opposite direction,” he says, “oftentimes exchanging pleasantries, and glances, and maybe, you know, following up on that.”

For lowriders, the whole point of the cruise is to see and to be seento show off the fruits of their labor, and to possibly make connections in the process. This was true on Whittier Boulevard in East L.A., and it was true at King and Story in San Jose. Villarreal sees this as a direct outgrowth of the culture of the paseo.

“It’s all about riding around, getting out there and socializing,” he says. “The same principle applies to the concept of the paseo.”

Whether or not they know it, in lowriding, Chicano youths are connected to something that stretches back more than half a millennium: an ancient impulse given modern expression.

Later, in the 1930s and ’40s, California experienced a sudden influx of people fleeing the effects of the Dust Bowl. With them came cars.

“The Chicanos of the 1940s were influenced by the Okies of Oklahoma,” Villarreal says, citing Lowrider magazine founder Sonny Madrid. “The Okies and other Midwesterners were the first to customize their cars. But they had the racing-style cars, with the high back end. Chicano youths adopted this idea and added the lowering of the car. So instead of high and fast, they went low and slow.”

NO CRUISING ZONE

For film lovers, 1979 was a landmark year. Alien, director Ridley Scott’s second film, would prove to be one of the most influential horror movies ever made, introducing audiences to the iconic heroine Ellen Ripley in the process. Released that same year, one of the most infamous and storied productions of all time nabbed the Palme d’Or at Cannes: Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

But it was a much smaller production from 1979 that would have a profound effect on California’s Chicano community. Director Michael Pressman’s Boulevard Nights took Los Angeles’ growing lowrider scene as its focusand muddied some facts in the process.

The story of two Chicano brothers growing up in East L.A., Boulevard Nights drew an explicit link between the cruising on Whittier Boulevard and the gang violence occurring in the city. In it, Richard Yniguez plays Raymond, a peaceful kid who loves cars and plans to open an auto repair shop. His younger brother Chuco, on the other hand, is prone to violence, and a member of the street gang “VGV.” Crucially, both brothers lowride. An early scene depicts a brawl breaking out in the middle of a cruise between Chuco and the VGV, and their rivals, the 11th Street Gang. Shortly after it begins, police arrive to break up the violence.

“Boulevard Nights associated lowriding with gang activity,” Arturo Villarreal says, “and all of a sudden, that stereotype arose around this time.”

The American Film Institute notes that “approximately 50 protesters, objecting to the film’s stereotypical portrayal of Mexican Americans as gang members,” assembled at the March 21, 1979 premiere. Later protests were assembled by the Mexicano-Latino Anti-Defamation League, the Coalition of Chicano Community Workers and MECHA.

No matter who you ask, everyone remembers the cruises differently than how they’re depicted in the film.

“The lowrider goals were always very positive,” says Biney Ruiz. “There was no fighting; they were hardworking. They were very disciplined.”

“There are rules and regulations for the car clubs,” Suzanne Lopez points out, drawing on her decades of work documenting California’s clubs. “It’s not that image that a lot of people have, that these are just homies, gangbangers, drug dealers. We’re family folks. We’re parents and grandparents, tías and tíos. We just happen to have the love of lowriding, and the love of cars.”

But the damage was already done. In 1979, shortly after the release of Boulevard Nights, L.A.’s Whittier Boulevard, the founding site of the lowrider world, was shut to cruising. Not long after, it began to happen in San Jose, too.

“In the ’80s, you began to see the ‘No Cruise Zones’ on El Camino, Santa Clara [and] of course, King and Story,” says Villarreal. The only threat, he adds, “was from the police, who continually pulled us over, harassed and ticketed lowriders.”

The media, it must be said, was no more helpful.

“Cruising Crackdown Results in 45 Arrests,” reads a Feb. 25, 1980, headline of one San Jose Mercury News article featured in the exhibit at the time. “Police arrest 59 in weekend sweep of cruiser haunts,” boasts another, from earlier that same month.

While the headlines would lead readers to believe police were intervening in widespread gang violence (exactly the kind depicted in Boulevard Nights), it’s only noted partway through the first article that rather than violence, weapons, or drugs, “most of the arrests…were for misdemeanor alcohol violations.”

“They for sure didn’t understand it,” Ruiz says. “It’s never been about fighting. They helped each other out; they would have gatherings, they would have barbecues, baseball games, Toys for Totsthey were into the community, and they were doing good things.”

Though cruising was now treated like a crimethe victim of a massive cultural misunderstandinglowriding continued, and in 1995 the San Jose Low Rider Alliance issued its founding charter. From the beginning, countering the stereotypes was a clear goal.

“This introduction is in hopes that the Low Rider Community and the San Jose Police Department can work together to solve the many problems that are in the communities of San Jose,” the charter states. “These problems range from Police harassment to poor human relations with the public.”

At MLK, a “Bronze Award” certificate from Second Harvest Food Bank (also issued in 1995) thanks the San Jose Low Rider Alliance for their donations. Below it in the display case is a letter from another program.

“The Low Riders are commended for the thoughtfulness and professionalism extended to the Latino community of San Jose,” it states. “Without the help of all the wonderful volunteers, there would not be 50 new potential marrow donors to the National Marrow Donor Registry.”

ROLLING ON

Today, lowriding is as recognizable a part of American culture as the car itself. But in San Jose it has become scarce, as the popularity of the pastime has declined and more of the Chicano community is being priced out.

Audience members at the MLK Library presentation were feeling the squeeze.

“This city is wiping away Chicano culture every single day,” San Jose resident Liz Gonzalez said to a smattering of applause.

“Don’t let Google buy us out!” another shouted.

Unfortunately, it may already be too late. In an effort to bring Google to San Jose, Mayor Sam Liccardo, along with many members of the City Council, signed non-disclosure agreements with the $110 billion company. Worried citizens have no way of knowing what went into the deal, or exactly how much city officials profited from a land deal that will only further gentrify the once egalitarian city.

Joey Jam, nephew of Lowrider magazine founder Sonny Madrid also singles out Google, stating simply, “This is taking away our culture.”

But efforts remain to keep lowriding a part of San Jose. As recently as last year, a new lowrider alliance was formed: the San Jose Lowrider Council.

“People in San Jose started really feeling the need to organize because of the way things are going,” says David Polanco, president of the council.

Last July, the council held its first meeting at a warehouse in the city’s industrial district. As an organization, the council aims to unite all of San Jose’s car clubs around common goals of “community outreach, youth outreach and maintaining the culture of lowriding.”

“It’s possible,” Polanco says. “Other cities are doing it. We just want to get in good with the city, be on the up and up, and give back at the same time.”

While King and Story may never again be what it once was, San Jose’s lowriding culture is being passed down to a new generation of enthusiasts.

That is certainly the case with Robert Velasco of RS Hydraulics. His two sons are both actively engaged in the family business and are involved with local lowrider clubs.

As for Suzanne Lopez, when her son graduated from high school, she bought him a ’67 Impalajust like the one her mom bought when Suzanne was 10. As for the originalthe car that changed the course of her life?

“That one is in my garage,” Lopez says. “We’re in the midst of restoring it. I’m going to hand it down to one of my grandsons.”