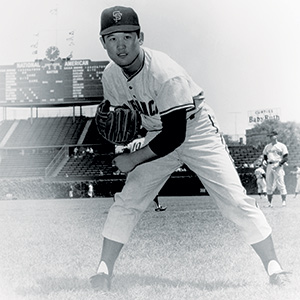

In 1964, a Japanese southpaw named Masanori Murakami, a.k.a. Mashi, came across the Pacific to pitch for the Class-A Fresno Giants. Later that year, when the San Francisco Giants called him up in the heat of a pennant race, Murakami became the first Japanese player in the major leagues. Unfortunately, confusion surrounding a contract with his club back home, the Nankai Hawks, prevented his U.S. career from taking off.

Now, baseball historian Rob Fitts has written Murakami’s definitive story: Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer; and both he and Mashi will make two appearances this Saturday in San Jose.

Near the beginning of the book, Fitts tells how baseball was introduced to Japan by American teachers in the early 1870s, soon after Japan had opened up to the western world. We get a glimpse into just how different the sport became for the Japanese. Taking inspiration from martial arts, especially judo, the Japanese brought a “mind and spirit” type of aesthetic to the game that did not exist here.

As Japan was just beginning to embrace foreign trade and western ideas, a term emerged: wakon yosai, which means “Japanese spirit, Western technology.” Teams modeled their practices after how they believed samurai warriors would prepare for battle. Players respected the field and the uniforms in the same way a samurai respected an heirloom sword. Techniques of extreme mental endurance and harsh discipline emerged, like practicing a fastball against a brick wall until a hole was bored into it. Teams would field ground balls for hours on end, until they vomited from dehydration. Complete subordination to the team mentality was required, sort of like the groupthink that would later occur in Japanese businesses.

Much of this aesthetic still lingered by the time Mashi came along in the mid-twentieth century. After the Nankai Hawks sent him to Fresno, the differences between the Japanese game and its American counterpart blew him away. In Japan, players never expressed their frustrations or inappropriately lost their tempers on the field. That was considered a loss of face. Players never questioned their superiors or argued with the umpires. In the US, when Mashi saw players throwing bats, kicking chairs and insulting the umpires over bad calls, such behavior seemed totally bizarre.

Mashi also became schooled in the aesthetics of bench brawls, which didn’t really exist in Japan, since Japanese players weren’t allowed to express their emotions. In the US, even if a player wasn’t prone to fighting, he was required to take the field whenever a fight emerged. One couldn’t remain stoic and sit on the sideline—you had to charge the field and join the brawl even if just pretending. It was an unwritten rule. Again, Mashi had never seen such a phenomenon, but it taught him that he was now allowed to open up emotionally.

“These were not violent men, nor were they showing disrespect for the game,” recalls Mashi in the book. “Instead their acts exhibited how seriously they played baseball. After watching the fight, I began to show my emotions when I was frustrated.”

And what better place to finally lose his temper than San Jose? On June 21, 1964, Mashi entered the field at Municipal Stadium to close out the second game of a doubleheader against the San Jose Bees. Thanks to a lousy call, he couldn’t get the job done. Afterward, Mashi broke a chair in frustration, the first time he ever did such a thing.

The book is chock-full of similarly intriguing anecdotes and I won’t spoil the details. Fitts does a great job illuminating specific characters in the backstory. Some examples: Cappy Harada was the shady wheeler-and-dealer who orchestrated Mashi’s confusing loan to the Giants. In Fresno, Manager Bill Werle was the man responsible for converting Mashi from a starter to a reliever, precisely what led him to the majors.

Fitts, along with Mashi himself, will make two appearances in San Jose this Saturday. At 1pm, a presentation and signing takes place at the Main Library. At 5pm, they appear at Nikkei Traditions in Japantown.