The Ivorian painter Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, who died in 2014, is the subject of a new exhibit at the Cantor Arts Center. Curated by Amanda Maples, Alphabété: The World Through the Eyes of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré presents a wide-ranging series of his colored pencil drawings.

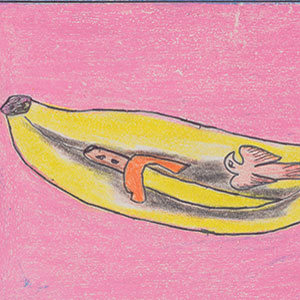

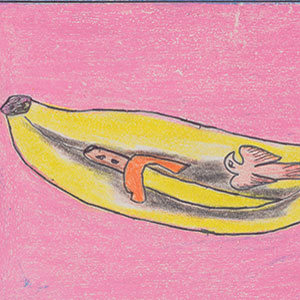

There’s a yellow banana on a pink background, the gray body of a snail emerging from a striped orange and brown shell and various portraits. All of the images are centered, or off-center, in a thin blue frame that the artist has drawn.

And, around that frame, Bouabré writes lengthy, poetic titles like the one he came up with for the banana, Une banana jaunie offrant une divine peinture, ici, “l’épée” joue le role d’un prince sacré favorable une douce union (A yellowed banana offering a divine painting, here, “the sword” plays the role of a sacred prince favorable to a sweet union), 2006. The inky words creep around the edges of the frame, telling us, in Bouabré’s case, that a banana is not just a banana. It also contains a sword and what may be a dove.

Maples introduces us to the work by writing, “When viewing Bouabré’s work, one may be tempted to see primeval drawings uncontaminated by Western art, made by a naive, untrained, ‘outsider’ artist.” During a recent phone interview, Maples, whose curatorial fellowship for African and Indigenous American art at Stanford recently ended, explains her defense of Bouabré and African art in general:

“In some of the gallery talks I’ve given, or the people I’ve talked with in galleries, they’ve looked at some of the African art, or even in classrooms, and said, ‘That’s not good. That’s not a trained artist,'” she says. “That misses the point. He’s [Bouabré’s] intentionally drawing things in a simplistic manner so that the work can translate to anyone in the world.”

Maples, who has been in the field for 15 years, recently accepted a position as curator of African Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art. She has often encountered art historians who contend that African art is derivative of Western art. Maples observes that “any time an African picks up a paintbrush or something that is a Western medium, it’s not inventive and creative from an African or a visionary standpoint.”

She believes that’s wrong-headed and a problem in the field. Maples notes that, “African art only started getting recognized, particularly contemporary African art, in the last decade, if that.”

As for Bouabré’s entry into the contemporary African art world, he had a career in the French government as a civil servant before having a spiritual vision in 1948that’s when he devoted his life to making art.

“He quit his job and quit doing anything except for being an artist,” Maples says. “Part of his practice was voraciously learning about the world. He wanted to read everything, to build this encyclopedic knowledge of the world.”

We get to see the man himself at the museum in video excerpts from Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: The Universalist, a short documentary about the artist by Andres Alvarez. An elderly Bouabré walks the city streets, collecting material to work with and dispensing wisdom like a wandering sage.

He talks about his diverse interests, such as an early love of Victor Hugo, but African myths inform the work we see him drawing at the end of his life. There’s a man with eyes all over his body, and a yellow sun showering rain/sperm on the belly of a pregnant planet Earth. The narrator asks him, “Rain is when the sun and the earth make love?” Bouabré replies, “When it rains, many things spring forth from the earth: children, trees, animals and so on.”

In another short filmBruly Bouabré’s Alphabet by Nurith Avivpeople demonstrate entries from the 448-letter alphabet he based on the oral tradition of his people, the Bété. The participants pick up one of his colorful pictograms, with a picture of a lizard or an arrow, and then pronounce the syllable that’s associated with it and written on the drawing.

“Bouabré was interested in highlighting oral history as a valid and rich way of translating and transcribing the world,” Maples explains. “He wanted to make those pictographs to visualize the history of those oral words. He’s not trying to replace it. His work is just thought of as complementary.”

Alphabété: The World Through the Eyes of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

Thru Feb 25, Free

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford

museum.stanford.edu